Saturday Feb 28, 2026

Saturday Feb 28, 2026

Wednesday, 9 September 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Ranil Wickremesinghe no doubt would have liked to have a lean and mean Cabinet but the voters of this country have forced his hands otherwise

The increase of ministerial portfolios from 30 to 48 in the context of a National Government has caused consternation all around.

During the Rajapaksa presidency we had to watch with resignation the endless parade of ministers, including a minister for botanical gardens, being sworn in. Civil society seems to have forgotten how close the country was to a continuation of the Rajapaksa presidency to several decades or more.

The victory of the present President in the presidential election of 8 January, where an unlikely combination of Opposition forces ran against a seemingly unassailable incumbent, is stranger than fiction indeed.

Having juggled to secure the presidency and then to form a minority Government in the general election, the President and Ranil Wickremesinghe are engaged in a tightrope act of governing, the likes of which we have not seen before. In consideration, I suggest we cut the Government some slack and see how we can build efficiency, effectiveness and accountability within the 48+35=83 Cabinet which seems to be our destiny at this point.

When Lee Kuan Yew formed his first cabinet in 1959 there were only 10 portfolios including the Prime Minister and Deputy Prime Minister. There were Ministries for Home Affairs, Finance, Labour, Law, National Development, Health, Education and Culture.

Ranil Wickremesinghe no doubt would have liked to have such a lean and mean Cabinet but the voters of this country have forced his hands otherwise. After analysing the 43 Cabinet portfolios awarded to date, against a set of 16 core portfolios, I see possibilities in making this big Cabinet actually work. This article is the first in the series in that regard.

Core portfolios

Academics who make policy recommendations often make the mistake of thinking they know better than politicians. Nothing is far from the truth in public policymaking. What I typically prescribe and follow is an empirical approach to policy recommendations where I try to frame the outcome of political rough and tumble and hope that my frames would be useful in dealing with the next round of rough and tumble.

For example, in the present case, I compared and contrasted existing Cabinet portfolios from Singapore and USA and our own Cabinet of 2015 January to compile a core set of portfolios, hoping that politicians or civil society would find the set useful for managing or understanding and responding.

Even today, Singapore has a lean Cabinet of 17 portfolios with Communications and Information, Defence, National Security, Environment and Water Resources, Foreign Affairs, Culture, Community and Youth, Muslim Affairs, Social and Family Development, Transport and Trade and Industry added to the original eight to reflect changing times.

The Cabinet portfolios in the United States have remained largely unchanged from a core of 15 consisting of Agriculture, Commerce, Defence, Education, Energy, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, Housing and Urban Development, Interior, Labour, State, Transportation, Treasury and Veterans Affairs as the core with cabinet standing given more recently to administrators of the Environmental Protection Agency and Small business Administration, among others.

Putting these two systems together, a global core of sorts can constructed as ‘Agriculture, Communications and Information, Defence, National Development, Education, Environmental Protection, External Affairs, Finance, Health, Home Affairs, Human Services, Infrastructure, Justice, Labour, Trade and Industry and Transportation’.

Comparing this international core with what Maithripala Sirisena and Ranil Wickremesinghe put together in January 2015, we can expand the individual categories further to absorb new categories and include a myriad of popular portfolios such as highways, transport, ports, shipping and aviation, etc. under the ‘infrastructure’ label to get a set of 16 core portfolios as ‘Agriculture, Fisheries and Plantations, Communications and Information, Cultural and Religious Affairs, Defence, Development, Education and Employment, Environment, External Affairs, Finance, Health, Home Affairs, Human Services, Infrastructure, Law and Justice, Labour and Trade and Industry.”

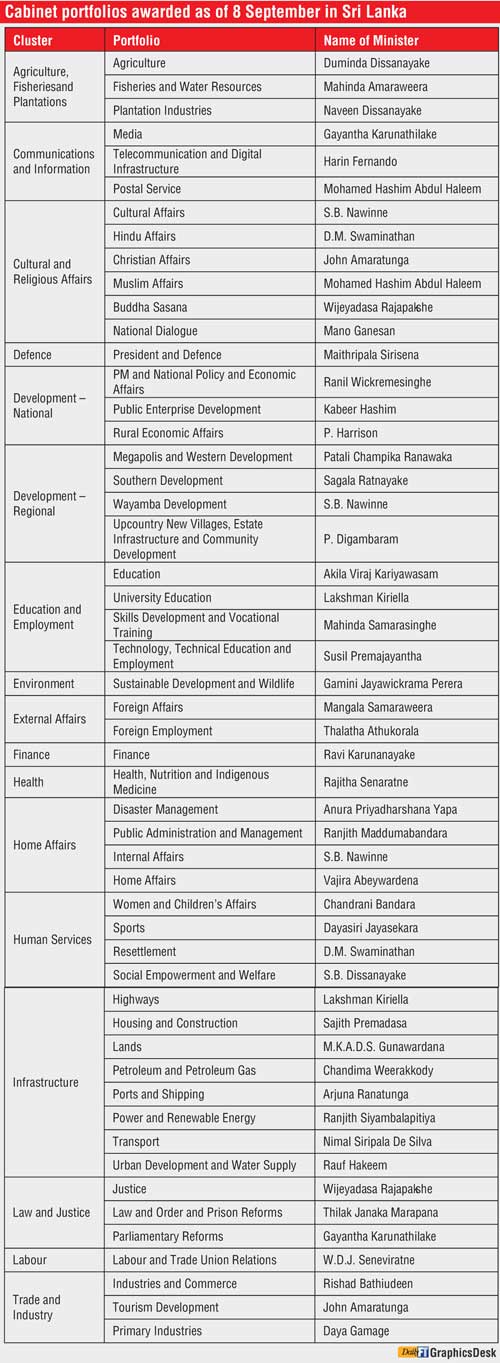

Forty three portfolios clustered into 16

To date, 43 ministers have been sworn in. I have clustered the 43 portfolios awarded so far within the 16 core portfolios we identified and summarised in the given table. This clustering is a work in progress and open to suggestions. We may also have to redistribute a few portfolios after we get more information on the 400+ Government departments and statutory bodies that are to be distributed among the ministries.

As is, the distribution seems to be well-thought-out with only a few overlaps within or across clusters, justifying the delay in appointments. Apparently, three more ministers are to sworn-in. Let us hope those will not cause too many overlaps and other problems.

Strong lineup, few possible overlaps and promising combinations

I find the Development and Infrastructure portfolios particularly well-manned. Kabir Hashim has the tough job of bringing together State enterprises under one umbrella company as promised in the UNP manifesto. P. Harrison from Anuradhapura sounds like the right person for the Rural Economics Affairs portfolio.

The Western, Southern, Wayamba and Central Provinces are targeted for development with leaders from each province, although Sagala Rathnayake from the Southern Province is yet to prove himself. The infrastructure portfolios too are manned by veterans except for M.K.A.D.S. Gunawardana for Lands and Chandima Weerakkody for Petroleum and Petroleum Gas, but the novices have the opportunity outshine the veterans. (These ‘muscle’ portfolios are manned indeed, without a single woman in the lot. I am not complaining though. Women have to rethink their tendency to corner themselves into women and children issues.)

We see some mismatches in the Education and Employment category where Technology, Technology Education and Employment portfolio is given to Susil Premajayantha and Skills Development and Vocational Training to Mahinda Samarasinghe. My first reaction to this separation was disbelief, but I am open to discovering the logic behind. Another vague area is in Home Affairs where S.B. Nawinne has the Internal Affairs and Vajira Abeywardena has Home Affairs, whatever each may mean. As the agencies are assigned to each portfolio, these distinctions should become clearer.

I find the Cultural and Religious Affairs core to be particularly promising if S.B. Navinne and Mano Ganesan use their respective Cultural Affairs and National Dialogue platforms to work with the four religious affairs ministries to gradually bring to the fore a Sri Lankan identity that rises above ethnicities and religions. I don’t know much about Nawinna but I have a lot of hope for Ganesan.

More after ministries and the affiliated agencies are gazetted.