Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Thursday, 10 September 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

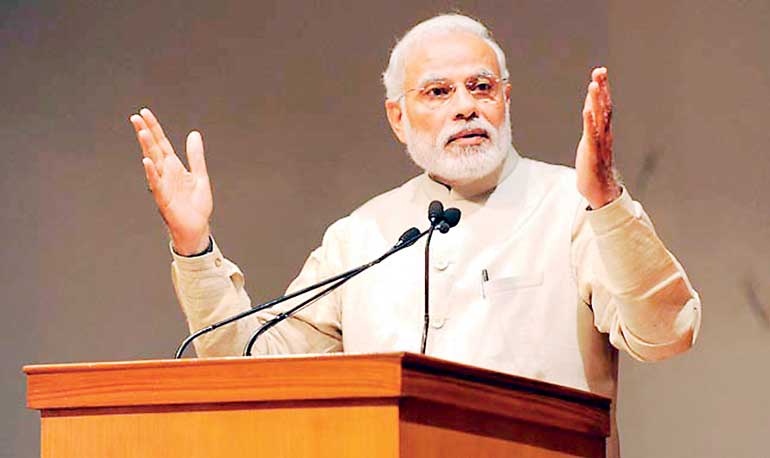

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi is promoting a SAARC satellite project as a gift to its neighbours. India’s Minister responsible for the Department of Space, Jitendra Singh, said: “The objective of this project is to develop a satellite for the SAARC region that enables a full range of services to all our neighbours in the areas of telecommunications and broadcasting applications like television, DTH [direct-to-home broadcasting], tele-education and disaster management.”

While appreciating India’s kind offer, it would not be out of place to discuss how best to utilise it.

Telecommunication

In the 1960s, the highest-profile use was for telecommunication, where massive antenna connected to a single satellite provided a qualitatively superior solution for international backhaul over the extant methods of copper cables wrapped in gutta-percha or radio waves that bounced off the ionosphere. Here, the satellite appeared stationary relative to earth because it was in the Clarke or geostationary orbit. That technological revolution of their youth appears have been deeply imprinted in the minds of today’s decision makers.

But this particular use is now obsolete. The cause is physics. Geosynchronous satellites are located 35,786 km above sea level. It takes more than 500 milliseconds (or more than half a second) for a signal to complete the full hop (up to the satellite and then down), resulting in high latency, or delay. Latencies greater than 300 ms are unacceptable for most present-day communication applications. Satellite transmission now fails to meet user expectations and system parameters which have been shaped by the short latencies made possible by fibre-optic cables.

Satellites are still used for telecommunication in regions with low population densities, including isolated islands with small populations, such as those in the Pacific. These satellites are placed in low-earth or medium-earth orbits (LEO/MEO satellites) to keep latencies at acceptable levels. However, this requires complex hand-offs between satellites, because LEO/MEO satellites are not stationary relative to earth.

The amount of data they can carry is less than what fibre-optic cables can. Thus, they are rarely competitive with fibre backhaul in densely populated regions such as South Asia, perhaps with the exception of Bhutan and remote and thinly populated northern parts of India, Nepal and Pakistan. They may also be useful in Afghanistan due to security problems, but plenty of terrestrial cables were laid in that country in the past decade.

In addition to the significant amounts of terrestrial fibre-optic cables that have been laid in all SAARC countries (including between islands/atolls in the Maldives and key population centres in Bhutan), the experimental international/domestic backhaul options offered by Google’s Loon project in Sri Lanka should also be considered.

Broadcasting

A geostationary satellite is in effect a 35,786 km high broadcasting tower. A signal broadcast from it can be received by any antenna within the line of sight, which would be the entirety of South Asia. Broadcasting satellites are heavily used throughout South Asia for supplying broadcasting content direct to the home and also to cable systems where they exist.

The conventional broadcasting model is likely to last for at least another decade. If the existing private satellites do not offer enough capacity or if their prices are too high, there may be merit in supporting the launch of one or more broadcasting satellites. But there is no justification for expending public funds on activities well supported by private investors. Governments can even make money by auctioning available orbital slots.

However, if governments are courageous enough to totally dispense with terrestrial broadcasting that relies on scarce electromagnetic spectrum and move all television broadcasting to satellites in the course of the digital transition, there could be a case for government subsidies. Valuable spectrum can be freed up for mobile and broadband applications. Revenues from these more valuable uses will more than make up for the subsidies to satellites.

Earth observation, including weather

India currently operates a number of earth observation and weather satellites. While INSAT is a geostationary weather satellite, there are significant advantages to sun-synchronous satellites using polar orbits which India also operates.

Observational data collected during multiple passes over the same terrain, using more than the visible range of the electromagnetic spectrum, provide valuable insights including the locations of fishing boats and fish stocks, forest cover and deforestation, the spread of pollution or forest fires, and so on. To be truly useful, a system of satellites is needed not just one.

India may choose to work up agreements that assure SAARC member countries shared access to the data collected by its satellites. Alternatively, SAARC may choose to launch earth observation satellites for use by member states and also work up arrangements for governance and data sharing. In either case, security considerations will have to be taken into account. Given the organisational capabilities of SAARC, it is logical that India launches and operates the satellites.

Collecting data is just the first step. The complete benefits of earth observation flow to those who can fully analyse the data. That is something the governments of the region can support, though again, not necessarily through a cumbersome inter-governmental organisation. INTELSAT and Eutelsat, which began as intergovernmental entities, are now fully privatised.

In sum

The primary value proposition for a single geostationary satellite that will serve all SAARC members is broadcasting. If it can be integrated into a coordinated digital transition strategy for the region, the outlay of approximately $ 40 million can be recovered. Artificial limitations on channels can be overcome, allowing for the full play of the creativity of the region’s content providers.

A geostationary satellite has no value for telecommunication in the SAARC region. A LEO/MEO satellite system may have some niche applications in remote parts, but it is a low priority for the densely populated SAARC region. The complexity of the technology and the nature of competition in the backhaul segment pose substantial risks that are best handled by commercial providers, not governments or intergovernmental organisations.

In the case of earth observation, including weather, the optimal results will be achieved from a system of satellites operating in orbits other than the geostationary. The conversation so far has been on a single SAARC satellite. Therefore, it appears that further engagement with the scientists in the respective countries is justified.

The legal arrangements pertaining to access to data which have security implications need attention. Building capacity to analyse the data generated by earth observation satellite systems requires the concerted efforts of the scientific communities in each of the SAARC countries.