Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Wednesday, 21 October 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Regional agreements

The Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement is a big deal. It covers 40% of the world economy and is the first major regional trade agreement reached in a long time. It represents a successful attempt by the United States to consolidate its relationships with the economic powerhouses of Asia and even to partially marginalize China.

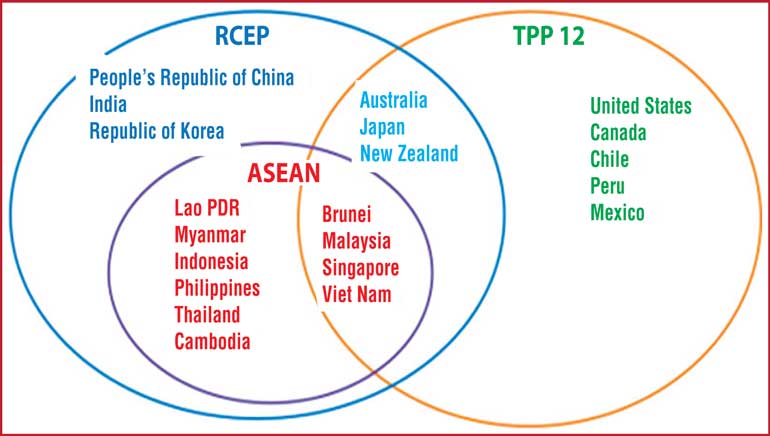

Proponents of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) which has ASEAN at the centre and includes India and China are scrambling to respond. One possibility is a Free Trade Area for the Asia Pacific (FTAAP) that would encompass the TPP and the RCEP. The RCEP members are the 10 countries of ASEAN (among whom Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam are also part of TPP) plus the six countries which have trade agreements with ASEAN, namely Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea.

China’s central bank has estimated that exclusion from the TPP may cost that country 2.2% of GDP growth. If the TPP clears the approval process in the US Congress, it is likely that it will attract more members. These countries will have to accept the terms already negotiated. South Korea is seen as likely to join first as it has been included in TPP negotiations since 2010 after the successful conclusion of its free trade agreement between the United States of America.

Other economies that have indicated interest in TPP membership include Taiwan, the Philippines, Colombia, Thailand, Laos, Indonesia, Cambodia, Bangladesh and India. Among the littoral states of the Bay of Bengal, only Sri Lanka is sitting on its hands.

Exclusion from trade agreements

Those who play only in the little Sri Lanka pond and read only our media may be surprised by all these countries wanting to enter into trade agreements. Aren’t trade agreement bad? Why are all these countries misguidedly seeking to enter into them?

Trade agreements lower tariff barriers for goods. This creates incentives for trade diversion. That is, countries that were previously sourcing from China may now start buying from Vietnam, solely because of the lower tariffs, not actually lower prices.

All modern trade agreements also remove or reduce frictions involved in trade in services. This enables firms to buy the best-quality services needed for their production processes, and also for service exporters to sell in a larger market. This enables greater productivity gains in the economies that have trade agreements as against those which do not.

Trade agreements also make the movement of people needed for highly productive economic activities easier. As production processes become more sophisticated, they tend to use more specialized services, consultants and experts. In advanced economies, foreign personnel are seen as resources that help grow the pie, rather than as those taking a share of a static pie. The TPP, for example, lays down detailed provisions simplifying visas and travel for business persons. So firms outside the TPP will find themselves at a disadvantage when supplying goods or services to member countries, relative to those entitled to the simpler procedures.

Most importantly, those who are outside trade agreements that cover goods, services and investment, are likely to be at a disadvantage in terms of participation in global value chains. Modern trade agreements provide a framework and legal certainty necessary for the fluid movement of capital, skills and resources at the heart of these value chains.

Implications for Sri Lanka

The United States which is driving the TPP is a major trade partner. To the extent that US buyers fund it easier to do business with firms in TPP countries such as Vietnam that are direct competitors, the TPP will have a negative effect on certain sectors.

But even more significant impacts will be felt when large, significant and proximate markets such as India and Indonesia join regional trade agreements that Sri Lanka is not party to. While the US and the EU are at the present time the most desirable export markets, the growth is going to be in Asia. If, because of the uninformed and backward-looking objections of vocal protectionists, Sri Lanka fails to follow through on the trade and investment agreements for which mandates were sought and received by the United National Party at the August 2015 election, we are likely to be stuck as a small-scale supplier of simple inputs and excluded from the provision of sophisticated goods and services within global value chains.