Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday, 9 December 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The 2016 Budget of the Government of Sri Lanka identifies several key issues facing skills development in the country. Foremost is the familiar story about gaps in the supply of skills and the mismatch between supply and demand. More significant is the identification of the structural problem of 400+ Government training institutions operating in isolation and the more fundamental issue of the examination-centric nature of basic education in Sri Lanka.

The gaps and mismatch issue is addressed quite explicitly in the Budget. National Youth Services Council is to be revitalised as a transit point for youth pursuing further education, training or moving onto a job. Private provision or public-private partnerships (PPPs) for making skills development more relevant too are proposed. However, the proposals are negated somewhat by a long list of new programs to be added to existing Government institutions or new Government institutions to be established without any mention of how they should make themselves more relevant.

It is also proposed to strengthen industry sector councils to align training provided to the needs of the private sector, but, the concept is not pushed any further. In this brief, we will explore how the revival of the NYSC, the introduction of a national qualifications framework and the extension of PPPs and sector council concepts across the board to all skills development activities will address the gaps and mismatch issue more effectively.

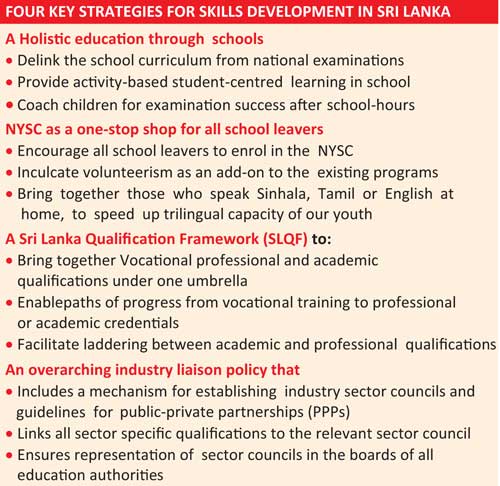

Regarding basic education, the Government has identified the need to “move away from an examination-centric, content based curriculum towards a competency based curriculum, helping children to gain life skills and to encourage independent thinking.” However, the proposed policy measures are limited to investments in infrastructure and teacher training. Some mention of the need to deliver a different kind of education would have set the scene for a discussion on the kind of reforms needed. In this brief we will try to fill that gap and present some ideas to initiate that discussion. Overall, we propose:

Schools as places for holistic education

The Sri Lankan education system in practice is the exact opposite of the student-centred activity-based learning which is required for the 21st century. Teachers struggle to cover an astounding breadth of material because they have no way of predicting what will appear in the national examinations. The result is that those who pass the exams prove that they know a bunch of facts and those who fail have nothing to show for their time in school.

The school curriculum should be decoupled from the sets of question papers from past examinations and notions of what might appear in future examinations. Time spent in school should be devoted to deeper learning of key concepts through projects, labs and field trips so that students become critical thinkers and learn to learn. Coaching for examination success would be an activity that could be offered for students after school-hours.

Currently students follow the same material twice, first in class by harried teachers who face multiple demands on their time and then at tuition by those who have mastered techniques for examination success. It is time to accept the reality that teaching for examination success and teaching to develop the whole child are two different activities that have to be segregated and carried out in two different settings.

NYSC as a transit point for all youth

The National Youth Services Council established by Act 69 of 1979 is the brain child of the present Prime minister who was then serving as the Minister for Youth and Employment. Politicisation weakened the institution during the last 10 or so years, but it has been rejuvenated under the new government. Its role is to guide youth towards success by career guidance, leadership training and other support services.

Given the amount of time wasted by young people in this country doing nothing in-between exams, NYSC can be an enriching meeting place for all youth during those transition periods. Opportunities to volunteer or opportunities to become bilingual or trilingual can be offered using its youth cadres themselves as resources.

The majority of children in Sri Lanka grow up either speaking Sinhala or Tamil at home, but, in homes of the elite, the children grow up using English as their mother-tongue, irrespective of ethnicity. Society is segregated along these three languages and opportunities to properly learn a second language is rare. NYSC can be a place that helps these groups of youth to teach each other to be bilingual or even trilingual.

SLQF as a truly national qualification framework

A national qualification framework is a mechanism for connecting segregated systems of qualifications, but Sri Lanka is yet to develop a truly national qualification framework. The National Vocational Qualifications (NVQ) framework which was introduced by the Tertiary and Vocational Education Commission (TVEC) in 2002 follows the Australian and New Zealand frameworks closely. The NVQ reserves level 1-6 for certificates, diplomas and higher diplomas, and Levels 7-10 for degrees and above.

In contrast, the qualification framework developed by the Ministry of Higher Education in 2010 with World Bank assistance is more concerned with distinctions between a general degree and an honors degree or an MA and an MPhil and other university specific concerns. On the other hand professional qualifications in 40+ sectors from accountancy, architecture, and aviation to logistics, to teaching and tourism exist in their own silo so to speak. We need a SLQF that recognises the diversity of tertiary education qualifications and enables individuals to progress from one qualification to another or ladder across to another without being restricted to vocational, professional or academic silos.

Sector Councils and Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs)

The Budget speech mentioned only in passing that Industry Sector Councils would be used to advice the Ministry and the Commission responsible for technical and vocational education and training.

Even now industry sector councils exist under various names under different ministries or agencies. For example, National Apprentice & Industrial Training Authority (NAITA) appoints a National Industry Training Advisory Committee (NITAC) for each competency standard it develops. Ministry of Industries has its own set of sector councils. During the 2000 to 2007 period, eight industry “clusters” in the ceramics, coir, gems and jewellery, ICT spices, rubber, tea, and tourism sectors were formed by The Competitiveness Initiative (TCI), a USAID funded project implemented by the Ministry of Industrial Development then.

Whether it is more appropriate to set up industry sector skills councils as in Australia is a detail that needs to be examined further. Whatever the structure, it is important that there is representation by relevant industry sector councils in all advisory boards or boards of management of education related bodies including the Ministry of Education (MOE), National Education Commission (NEC), National Institute of Education (NIE), NYSC, University Grants Commission (UGC). TVEC and National Apprentice Industrial Training Authority (NAITA) are already well represented by industry sectors, but a unifying sector council for each industry is needed.

The 2016 Budget provides a variety of incentives for Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) in building and construction, hotel and tourism, light engineering and manufacturing, freight forwarding and auditing, for example, but new courses at Government institutions are offered without requiring linkages with relevant industry sectors.

These proposals include expansion of programs at the University of Vocational Technology (UNIVOTEC), Ocean University, establishing new University Colleges; upgrading of Colleges of Technology to the status of University colleges and Techno-based campuses; situating vocational training institutions alongside current universities; establishing universities in lagging regions, etc. A Sector Councils linkage policy or PPP mechanisms that applies across the board to all government institutions is sorely needed.

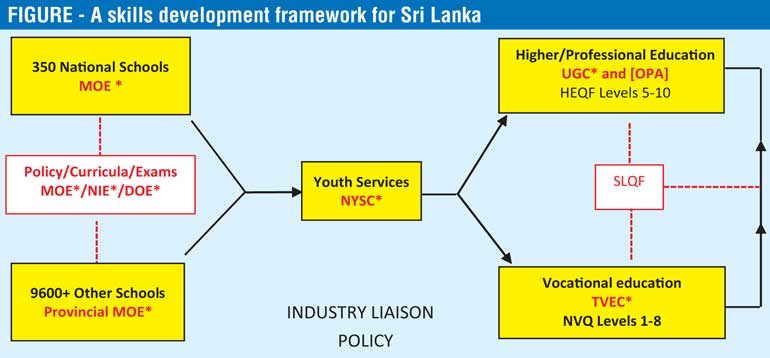

A skills development framework

A framework that helps one to visualise the four strategies would have an invigorated NYSC as the key transition point for about 340,000 youth who join the ranks of 18-24 year youth category in Sri Lanka. The importance of NYSC is underscored by the fact that fifteen percent of our youth would leave school before they face the GCE (O/L). Another 30-35% would leave after the exam but without the required six passes with language and math. Holistic educational reforms in the general or basic education sector to the left of the NYSC will help keep all children engaged and interested in school education.

Even those who get through the critical GCE (O/L) gateway often feel they get trapped in vocational or technical silos without opportunities to progress to higher professional or academic qualifications. Much publicised protests by the students in the Higher National Diploma (HND) in accountancy program is a case in point. A cross-cutting and unifying qualifications authority, like the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority of UK, to develop and maintain an SLQF is needed. An industry liaison policy shown as a box that envelops all institutions and relationships will include guidelines for establishing industry sector councils and PPPs for skills development in Sri Lanka.