Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Friday, 5 February 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Sulochana Dissanayake

It is never easy to make it to the theatre on a Sunday. However, when I heard through the grapevine that the creator of ‘Colombo, Colombo’ stage play was back in the country and about to stage his newest creation, ‘The Irresistible Rise of Mr. Signno’ to support his PhD research in Monash University in Australia – I knew it was a production not be missed. ‘Colombo, Colombo’ was one of the most thought provoking contemporary stage plays I had witnessed in Sri Lanka. So naturally, I went for ‘Signno’ brimming with expectations.

First off, the choice of venue (Asoka College Gymnasium) had the bare minimum infrastructure to support a public performance – the ticketing counter was a precariously balanced school desk lit by a mobile phone torch with two ticket sellers battling with an endless line of audience members. Having arrived at 6:20 p.m., I managed to gratefully purchase my tickets amidst loud drumming and burning incense and made my way to the gymnasium entrance through a path lit by vilakku (traditional coconut fire lamps).

The seats were individually numbered, basic plastic chairs and it took a while to locate the right seats. I wondered why the army of performers milling about was not trained to seat the audience members efficiently. A task that could have (with proper organisation) been done in 10-15 minutes took more than 30 minutes. In a sweltering venue without air conditioning, this was a brutal delay.

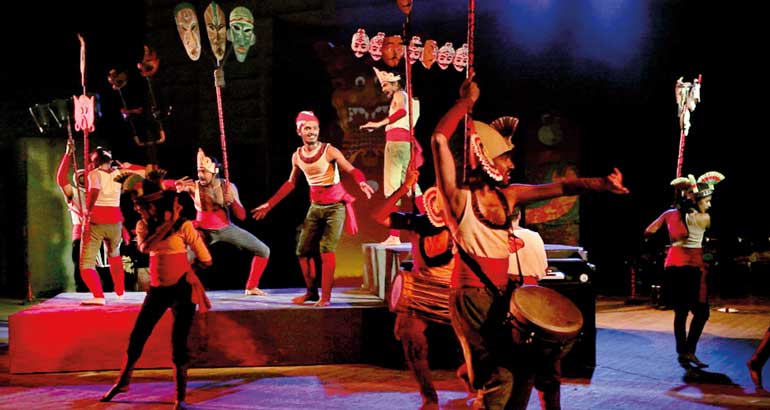

At last, close to 7:10 p.m., the performance began. Immediately, I was transported back to the Sri Lankan low country ritual performances of bali, thovil and shanthi karma by the drumming and the presence of live fire and the sensory immersion created by dance, music, dialogue and constant burning of incense. But this was a ritual with a tight story line. While my senses were being caressed and occasionally assaulted, my brain was occupied by the storyline which flowed like a stream around the vivacious chorus, musicians and the set.

The fact that the performance primarily used English for spoken dialogue was an unexpected twist – and a reminder that the local university talent is perfectly capable of performing a full length production in English.

Signno

The story itself intrigued me greatly. It was both mythical and mystical – and at times was based on easily recognisable realities. Signno is a suicidal-nobody who is the epitome of failure. He is so tired of failing at everything that despite of having wealthy parents who are able to lavish luxuries upon him, he decides to end his life ‘for a better life next time’. But in true Signno fashion, he fails even at suicide. His obsession with an unnatural death catches the attention of Wasawarthi Maara – who is the ultimate power of natural death.

Maara visits Signno to meet his best disciple (as no one else has sought after Maara at such a young age) and takes pity on Signno. Maara decides to grant a second chance in life to Signno by bestowing him the power of granting life to people on their death bed – under special conditions. At the end, the power of greed and the greed of power (which spares no god, demon or human) leads Signno to manipulate his benefactor, causing Maara’s demise.

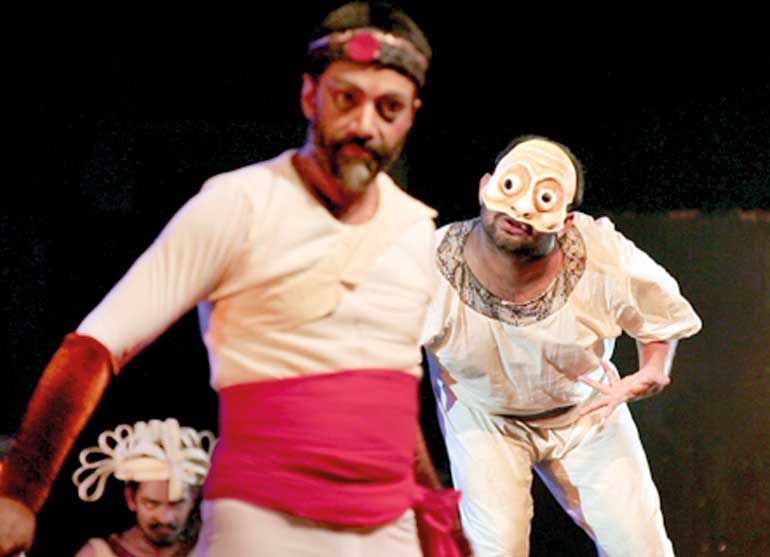

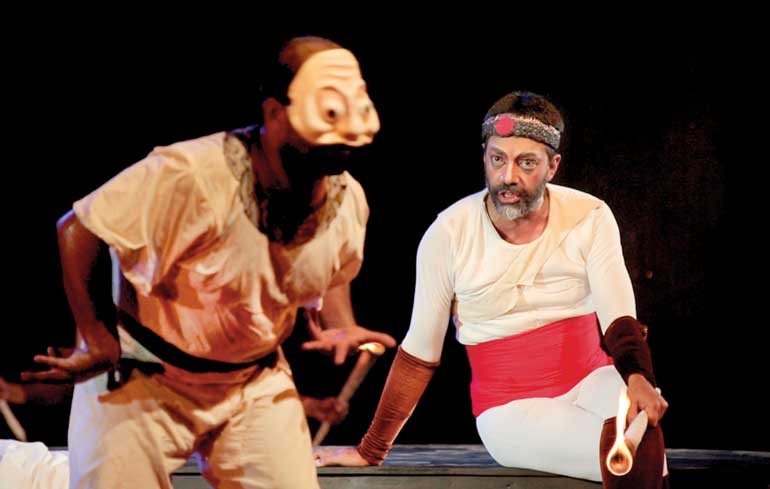

The character of Maara (performed by Saumya Liyanage) fascinated me, as in Buddhist mythology, Maara attempts to tempt Lord Buddha with lust before his enlightenment. Yet, in this parable, Wasawarthy Maara was the only character with genuine principles – and despite his reputation of being the most powerful demon, he too is vulnerable to human feelings of love, lust and desire. Signno traps Maara with promises of ‘being loved, honoured and desired for a day’ – instead of the usual reaction of fear, repulsion and rejection experienced by Maara – who yearns to be cherished as a life-giver and released from his exhausting duties of being a life-taker.

Signno compromises Maara’s wits by intoxicating him with ‘happy tears’ – a drink that is both foreign and addictive to Maara and when he is drunk past the point of no return, he is introduced to the luxuries of the human flesh by Signno’s concubines. The great Wasawarthy Maara crumples like a virgin teenager and exchanges his omnipresent power of death with Signno. Liyanage’s convincing portrayal of this multi-layered character who is so powerful and yet caught completely unaware by human deception (twice over) enabled me to sympathise with Maara – an unusual feeling considering he is the symbol of death and destruction.

The play ends with the blood pounding drumming and fire dancing of Maara’s army backing Signno as the ultimate power – a fittingly cathartic ending for all the emotions roused through this marathon of a show.

The use of low-country drumming and ritualistic movement, with contemporary masks echoing our ‘Kolam’ traditions, masterfully handled by a chorus who at times replaced spoken dialog with verbalised drum rhythms, riveted me for the full three hours of performance. This medium struck a very primal chord, yet narrated a tightly structured story with psychological depth that disturbingly questioned cultural and political norms and deep-seated beliefs.

Blurring of right and wrong

The transformation of the armies of humans (who were gifted a new lease of life from Signno) in to salivating hounds who heedlessly followed Signno was a particularly striking message of the production. It raised the pertinent question – is accepting a favour from forces in power only compensated by the complete renouncement of human dignity? The narrator aptly says, ‘It is said that a dog takes many life times to attain a human life in sansara – but a human can become a dog within seconds’. Moments like this, for me, captured the shame and guilt of a nation we have been grappling with for generations – caused by the blurring of right and wrong that each and every one of us do in the fight for survival.

Other highlights of the production for me included the pure genius in trapping Maara inside Signno’s wife’s womb – the stunning princess who is reduced to Signno’s slave as a result of her (selfless or power hungry?) act to save her husband’s life. The relationship dynamics perpetuated by cultural norms of our society were depicted by the zombie-expression on the princess’ face as she is imprisoned by both her chastity belt (locking Maara inside her womb) and the rope that ties her to Signno’s wrist – which again evokes the image of a pet being dragged around by its master.

She sings ‘London bridge is falling down’ while she watches her husband being pleasured by his concubines when her own marriage was never consummated – highlighting the hypocrisy of Signno’s marriage. Finally, she is torn to pieces to release the secret of Signno’s success by power hungry gods and demons alike, who first unite in their war against the Signno but then start battling amongst themselves in their quest to own ‘immortality’ – ensuing chaos depicted by a drumming and dance frenzy.

Salu Paaliya

A personal favourite of mine was the ‘Salu Paaliya’ who tries in vain to tell his story of God ‘Dedimunda’ (the god who defeated Maara) but who is constantly questioned and confused by the narrator – ‘the artist with bare hands’ – who Salu Paaliya correctly says is more dangerous than a murderer with a dagger. ‘Salu Paaliya’ is tricked, tortured and seduced to the point he forgets his own identity and his original purpose, and leaves us as a broken character – a mere shadow of his former self.

I couldn’t help but wonder if this isn’t what regularly happens to traditional artists in our ‘structured’ contemporary platforms – where we force them to adapt to our settings, which is so foreign to them that we are left with an echo of their original selves.

Signno (played by Stefan Tirimanne) sustained his tricky character right to a chilling end – appearing as a grotesque clown at the beginning and transforming in to a cult-leader without a conscience hiding behind a mask of benevolence. The Princess (played by Anasuya Subasinghe) evoked memories of Lady Macbeth in her fearless pursuit of power – and I wonder if she risked her freedom and sacrificed her true love to protect her betrothed (stranger) husband for the carrot of eternal power.

Her readiness to drop her true love and physically own Maara was a naked display of her own greed – only second to Signno’s all-consuming desire to be a universal super-power. Subasinghe perfectly balanced the tragedy and the dark humour of a trapped house-wife to the point where I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry for all the women trapped in scarily similar situations. The narrator (played by Saviour Kanishka) evoked the persona of a wayward pirate – belonging nowhere and difficult to ever pin down, and thus seamlessly blending in to the cosmos of the performance.

Salu Paaliya (played by Jithendra Vidyapathy) was both absurd yet heart-achingly recognisable – and gave a remarkably moving performance. All the main characters were fully-realised, complex and used their entire body in performance – a refreshing change to largely dialogue reliant ‘talking-heads’ performances that dominate both Sinhala and English stages of Sri Lankan theatre.

The main actors were supported by an equally impressive chorus who reached their full potential as a collective energy that fuelled the show from beginning to end, with detailed individual performances that etched each performer on stage into the memory of the audience. Not a single body was unnecessary or out of sync – which speaks volumes about the commitment and training that resulted in their hypnotising performance.

Clutches of greed unleashed by unlimited power

In summary, ‘The Irresistible Rise of Mr Signno’ truly drove home the fact that nobody is free from the clutches of greed unleashed by unlimited power – unless they have attained enlightenment. It awakened the burning need to look within rather than constantly blame others for crippling mistakes we have all contributed to with our biases, prejudices and perceptions. The sensory journey whereby the audience was constantly sprayed with smells, burning incense and the ‘magical’ mustard seeds also helped to transport us to the ritualistic world of performance.

I wonder if the performance would have worked better in an open air, theatre-in-the-round setting to further connect us to the essence of these ritualistic performances as visibility was compromised in the proscenium setting (due to all the chairs arranged on the same level). The minimalist costumes united by the red waist bands (evocative of the ‘pachcha wadama’ seen throughout the dance traditions of Sri Lanka) worked well for most of the characters, but I couldn’t help wishing for a slightly more prominent costume/head-dress for Wasawarthy Maara to symbolise his power and grandeur.

Overall, an encore-worthy, spell-binding reminder that our traditional performances are capable of narrating powerful stories to impact modern audiences – when conceptualised and executed by an innovative visionary like Indika Ferdinando. Thank you for this unforgettable treat and hats off to everyone who gifted this show to the Colombo audiences.

(The writer is Founder and Artistic Director of Power of Play Ltd. She is a graduate of Bates College, USA in Economics and Theater ‘09 and a Watson Fellow ‘09/’10 (Thomas J. Watson Foundation, USA). Keen on discovering the power of performance to build bridges across social, cultural and economical divides, she travelled to South Africa and Indonesia on a Watson Fellowship (2009/10, awarded by the Thomas J. Watson Foundation of IBM). Back in Sri Lanka for the foreseeable future, Dissanayake capitalises her experience in USA, Europe, Africa and Asia to customise unique communication solutions for corporate, governmental and non-governmental sectors of Sri Lanka. For more information, please visit www.powerofplay.lk.)