Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Tuesday, 26 April 2016 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Pathfinder Foundation’s Centre for Indo Lanka Initiatives

In the recent past several articles have been published in the local press with regard to the objections by Bangladesh to Sri Lanka’s claim of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from its coast baseline made to the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). The Dhaka Tribune dated 15 April quoting a senior official of the Foreign Ministry has pointed out that as Sri Lanka’s claim overlaps the continental shelf of India and Bangladesh, Colombo should complete negotiations with India first.

An essential function of the State is to establish and protect its territorial boundaries. On becoming a Party to the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), Sri Lanka, as an island State, was required to establish its maritime boundaries: the limits of its territorial jurisdiction, in accordance with the rules prescribed by that Convention.

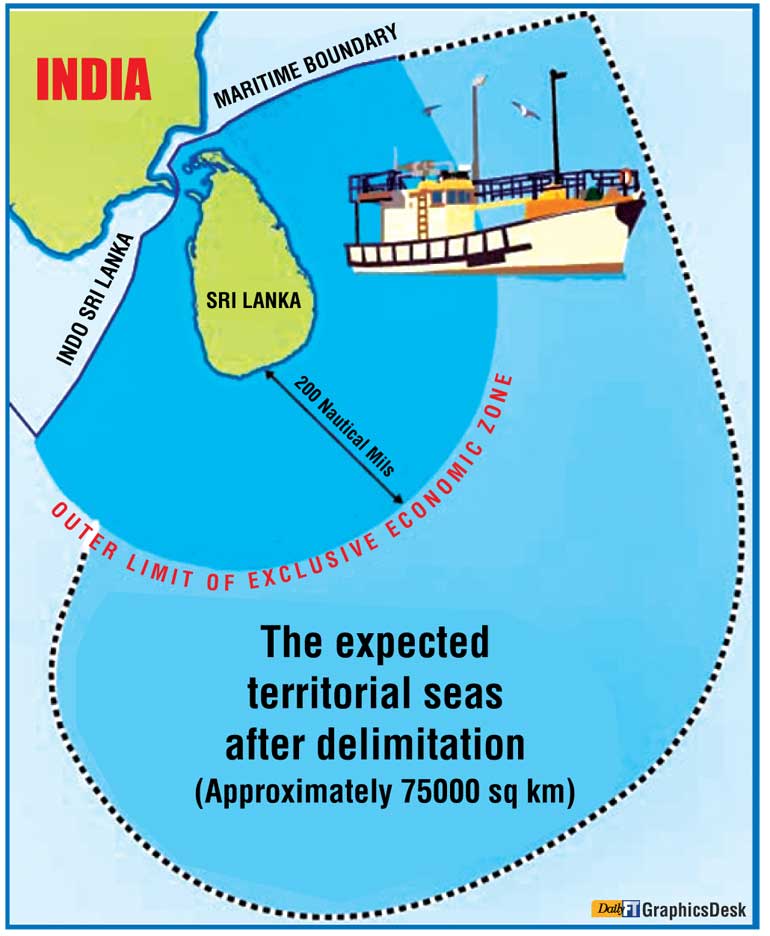

During the negotiations leading up to adoption of the Convention, Sri Lanka had already established the limits of the basic maritime areas over which it would have the right to make laws and regulations, and to enforce them: the Territorial Sea (12 miles from the ‘baseline’ (essentially the coast) over which it would have rights similar to those exercised over its land territory; the Contiguous Zone, 12 miles beyond the Territorial Sea in which it would have certain rights to prevent breach of its customs, fiscal, immigration and sanitary laws); the Exclusive Economic Zone, 200 miles from the baseline, in which it would have sovereign rights and jurisdiction for the purpose of exploring and exploiting natural resources both living (fish, seaweeds) and non-living (minerals, energy), while allowing other States to exercise the freedoms given by the Convention to use the area; the Continental Shelf comprising the sea-bed and sub-soil of the submarine areas that extend beyond the territorial sea throughout the natural prolongation of the land territory up to the outer edge of the continental margin, subject to constraints provided for in the Convention, up to a maximum distance of 350 miles from the baseline.

A proclamation was issued by Sri Lanka in January 1977 demarcating the extent of Sri Lanka’s Territorial sea, Contiguous Zone, and Exclusive Economic Zone, details of which were published and subjected to the laws of Sri Lanka when Prime Minister Sirima Bandaranaike was in office. Issues connected with boundaries with close neighbours India and the Maldives, as well as with the politically sensitive matter of Sri Lanka’s sovereignty over the island of Kachchativu, were all settled by agreement under her leadership.

Extent of Sri Lanka’s Continental Shelf

What remained to be established was the extent of Sri Lanka’s Continental Shelf under the provisions of the UN Convention to which Sri Lanka became a Party in 1995. All States are entitled to declare the limits of their Continental Shelves, but must now do so by first submitting specified technical data to the CLCS established by the Convention. If the Commission decides that Sri Lanka’s submission is in accordance with the rules of the Convention, that decision will be accepted by all other States and Sri Lanka’s maritime limits will be recognised by all States.

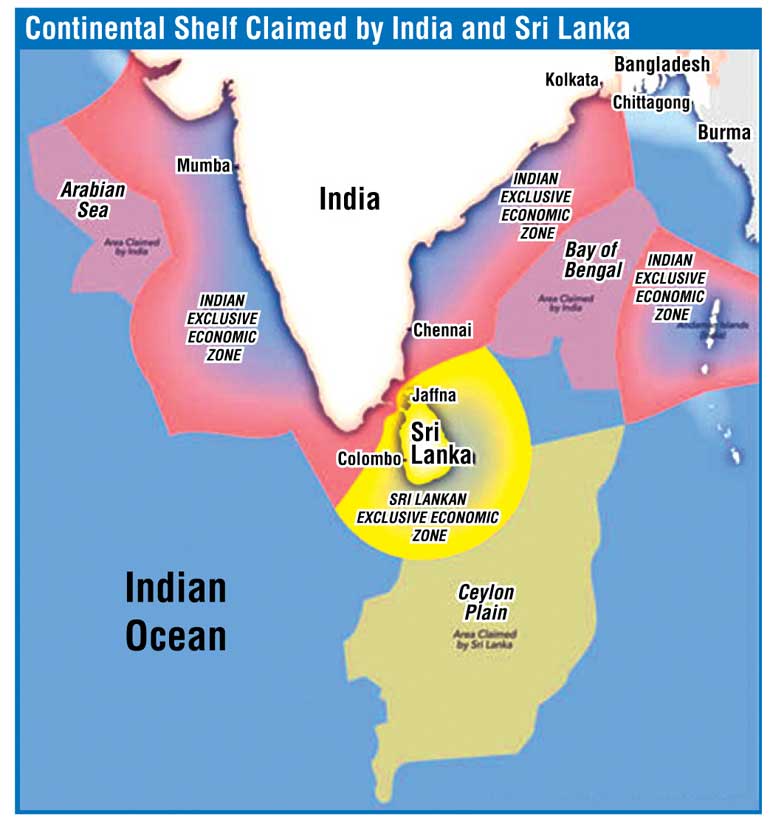

The Convention sets limits to the extent of the ‘Continental Shelf’ that a State may legally claim, together with its natural resources, e.g. an outer limit of 350 miles from the baseline. Because of the peculiar configuration of Sri Lanka’s Continental Shelf, application of the Convention’s ordinary depth and distance limits to the Continental Shelf would have unjustifiably deprived Sri Lanka of the full extent of its right to adjacent submarine areas and their natural resources in comparison with the extent permitted to other coastal States under the Convention.

In 1978/9, during the final stages of the UN Conference on the Law of the Sea, when the Sri Lankan delegation was able to obtain the relevant technical information and advice, they were able to convince all the negotiating countries of the inequity that could result to Sri Lanka, the Conference decided on a remedy for the ‘Sri Lanka problem’: the Conference would prepare a document to be attached to the Convention and binding on all countries, allowing Sri Lanka a special regime applicable to its adjacent submarine areas and resources, that would not be governed by the Convention’s ordinary limits and conditions, but only by the limits and conditions contained in that document.

That document, negotiated by Sri Lanka with the interested states, was adopted by all the States at the Conference, and now forms Annex II to the Final Act of the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, and bears the title ‘Statement of Understanding’ (SOU). Conditions in that document were, at India’s request, extended to India as a ‘neighbouring State’, where the configuration of its Continental Shelf resembled that of Sri Lanka. The Conference agreed that the SOU should extend to India as a ‘neighbouring State’ in the southern part of the Bay of Bengal.

In 2012, the Cabinet of Ministers created an inter-departmental Committee entitled the National Ocean Affairs Committee (NOAC) consisting of scientific and legal experts. As its first task, NOAC began preparation of Sri Lanka’s submission to CLCS on the limits of its Continental Shelf. Working with world-renowned technical and legal experts (e.g. from the United States, Russia, Norway, New Zealand) as well as Sri Lankan experts, approved and appointed by the Cabinet, NOAC prepared Sri Lanka’s submission to CLCS on the extent of its Continental Shelf.

That submission, consisting of considerable volume of documents and maps, was deposited with the Secretary-General of the United Nations, on 8 May 2009 within the prescribed time schedule. Over 40 maritime countries had submitted their claims before us. Consequently, Sri Lanka, has been on the list of countries awaiting an invitation to make a presentation of its submission to the Commission (CLCS) for the last seven years. Taking in to consideration the large number of maritime countries, who are ahead of Sri Lanka, it is estimated that our claim will not be taken up for consideration before 2025.

Overlapping entitlements and delimitation

The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea makes provision for delimitation of the continental shelf between States with opposite or adjacent coasts (Article 83), requiring the States concerned to effect delimitation ‘by agreement on the basis of international law…. in order to achieve an equitable solution’.

Pending such agreement, ‘The States concerned, in a spirit of understanding and co-operation, shall make every effort to enter into provisional arrangements of a practical nature and, during this transitional period, not to jeopardise or hamper the reaching of the final agreement’.

Delimitation of the Continental Shelf between States with opposite or adjacent coasts would arise, where their entitlements under the Convention appear to overlap. Where, as with some States in the Bay of Bengal, entitlements have not been agreed or declared by CLCS, any questions of ‘overlap’ and delimitation remain matters for conjecture, while subject to eventual resolution under the provisions of Article 83.

Recommended action

As there are other countries ahead of Sri Lanka in the ‘queue’ awaiting invitations to present their submissions to CLCS intend to claim that they are entitled to rights under the SOU, it is urgently necessary that Sri Lanka have consultations with India as joint beneficiary under the SOU, that would safeguard our (and India’s) interests. After consultation with India, Sri Lanka should also discuss with Bangladesh and Myanmar their claims, if any, to be entitled to the dispensation provided to Sri Lanka (and India) by the SOU.

It needs to be highlighted that negotiations with the interested countries will have to be carried out by competent technical and legal experts, who had gained a thorough knowledge having participated in the negotiations leading to finalisation of UNCLOS in 1982. Given the fact that those who were involved in such negotiations were senior officials representing Sri Lanka’s interests at that time, and considering the fact that there would be a gap of approximately 10 years before Sri Lanka’s case would be taken up by CLCS, it is essential for the authorities concerned to take urgent steps to transfer the knowledge and skills of those experts to a new generation of technical and legal experts, who would represent Sri Lanka’s interests before CLCS in a decade’s time.

It has been reported that Kenya’s submission is soon to come before CLCS, and that the Sub-Commission appointed by CLCS to deal with the Kenyan submission has been instructed to ‘consider the submission made by Kenya on a scientific and technical basis under the provisions of Article 76 of the Convention and the Statement of Understanding’.

It is considered that, in issuing this instruction to its Sub-Commission, CLCS may have exceeded its authority by presuming that the SOU is applicable to Kenya, which could not be regarded as a neighbouring State of Sri Lanka, and cannot possibly be considered to be anywhere near the Bay of Bengal.

Considering the foregoing it is recommended that Sri Lanka take urgent action to discuss the situation first with India and thereafter with other countries aspiring to take advantage of the SOU, as well as take urgent steps to train and equip a new generation of negotiators, who would successfully argue Sri Lanka’s case before the CLCS, when Sri Lanka is invited to present its case.