Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Friday, 8 July 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Many residents of villages in Aranayake are living in precariously cracked homes

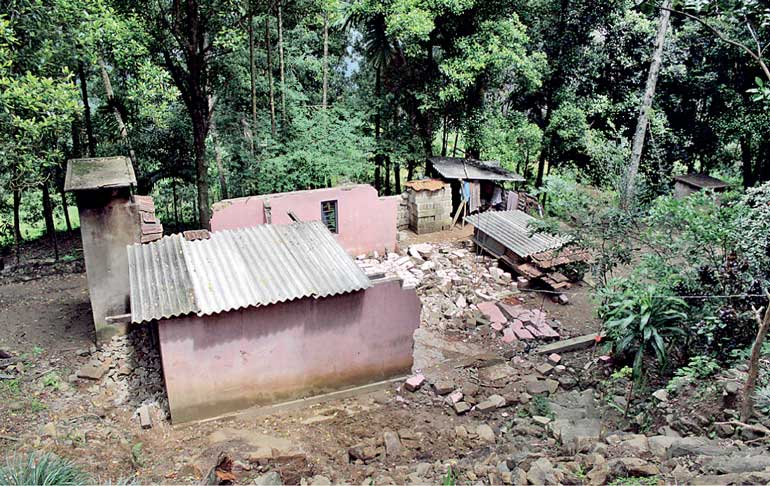

A house in Gamthuna, Aranayake that collapsed on the same day as the tragic landslide

Text and pix by Shiran Illanperuma

The soil beneath W. Gunasekara’s feet could give way at any moment but he refuses to budge.

A few weeks ago the 92 year-old’s home, situated just a few kilometres away from the Aranayake landslide incident was declared a high-risk zone by National Building research organisation (NBRO).

Gunasekara, along with his son, daughter-in-law and two grandchildren were advised to evacuate immediately for their own safety. Their neighbours – just a few meters away – were given no such instructions, leaving Gunasekara and his family baffled.

“I’ve lived my whole life in this house and I don’t see why I should leave when my neighbours can stay,” said Gunasekara. “We’ve heard of landslides in this area since the time of my grandparents but these officials have not explained to us why some of us have to leave. I’ve lived my whole life in this house and at this age I’m not ready to leave.”

The Gunasekara household is one of over 20, 000 families that have been identified as living in high-risk, landslide prone areas by the NBRO who are currently mapping districts throughout the area. NBRO Head of Landslide Risk and Research management division RMS Bandara told Daily FT that houses are being assessed on a case-by-case basis by scientists on the ground – a laborious process that can take half a day just to assess one small village.

“In the immediate aftermath of the landslide in Aranayake our immediate task was to demarcate areas according to the level of risk of landslides. We try to send a scientist to each household so that residents do not feel neglected,” Bandara emphasised. “Parallel to that we are also assessing land that is safe for settlement once we realised how many people would need relocation,” he added.

However, residents like Gunasekara perceive a lack of meaningful engagement and explanation on the part of the Government officials. In fact Gunasekara was uncertain of which branch of Government the representative who came to warn him was from. In addition homeowners are understandably unhappy at the prospect of leaving houses that may have taken years’ worth of savings to build to move into Government and NGO run displacement camps.

But recommendations for high-risk zone residents like Gunasekara to relocate to camps are not permanent. Plans are underway to provide every family displaced by the Aranayake landslides as well as those currently residing in high-risk zones with 20 perches of land each for relocation. The Government is also planning to build houses on these lands.

Land for resettlement will likely come from the public sector though some private owners are said to have come forth to donate their land. Despite this, finding suitable plots of land to relocate the high number of displaced families in the hilly Kegalle district is easier said than done. The NBRO has advised against building houses on altitudes higher than 900m – even if said land is flat – narrowing down the search.

Aranayake Divisional Secretariat Z.A.M. Faizal shared concerns over the speed of the mapping and relocating process: “There are around 8 NBRO teams working to map Kegalle but we need more to work faster. The 20 perches we want to give to people doesn’t even include the space needed for roads and backyards. It’s an ongoing challenge to find suitable land and to clear it in time to start relocating people who have been displaced.”

The Disaster Management Centre office in Aranayake initially told Daily FT that the figure of over 20, 000 families identified as living in high-risk areas is likely to increase over the coming weeks as the NBRO continues to conduct surveys throughout the area. However Bandara explained that initial figures were given to the DMC and local Government offices in bulk to stay on the safe side and that as individual assessments continued the number would eventually decline.

Said Bandara, “Using our preliminary list which featured bloated numbers as a safety measure we are assessing houses based on the drainage systems, their location on or below steep cliffs and their location in relation to the path of unstable rocks. Some homes that are on medium or low risk areas can be adjusted to strengthen their resistance to landslides while others are safe despite the adjacent ones being high-risk due to the topography of the area.”

While Ambalankanda, the settlement at the foot of a mountain known as Ramasara (or alternatively, Samasara) to residents was ground zero of the landslide last month and subject to the most attention, many neighbouring villages experienced smaller slips with piles of debris obstructing some roads and large ominous cracks running through many households.

“The need now is to ensure we avoid another Aranayake when the next rains are upon us,” says Bandara.

The question remains whether households like Gunasekara’s will heed warnings, especially ones that are not sufficiently explained to them by the relevant authorities. Additionally households like Gunasekara often prioritise immediate concerns such as proximity to schools and places of environment over long terms concerns of geographic security.

“Even if we move to a safer place what use is it if we are relocated to an area that has no schools nearby or takes us too far away from work. We could lose our livelihoods. Leaving is not so simple,” he says.