Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Friday, 12 August 2016 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

President Maithripala Sirisena and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe have different backgrounds, strengths and weaknesses. Among politicians, the Prime Minister is the country’s leading policy thinker by far. But the President, like President Rajapaksa before him, can connect intuitively with small-town and rural Sinhala-Buddhist Sri Lanka

Expectations were high after the January and August elections last year. The incoming Government promised a new era of political  liberalism, good governance, ethnic reconciliation and a balanced foreign policy. Not least, it stirred hopes of a more market-oriented economic policy that would, finally, make Sri Lanka achieve its long-heralded potential. What has changed in the last year-and-a-half?

liberalism, good governance, ethnic reconciliation and a balanced foreign policy. Not least, it stirred hopes of a more market-oriented economic policy that would, finally, make Sri Lanka achieve its long-heralded potential. What has changed in the last year-and-a-half?

To begin with credits: The political atmosphere is freer; the 19th Amendment and a new constitution in the works promise more checks on arbitrary power. Corruption is smaller-scale and less brazen than it was under the Rajapaksas. Ethnic tensions are much lower; the right symbolic overtures have been made to the minorities. Foreign policy has been rebalanced. Despite initial bumps, China remains a firm friend, but relations have been repaired with India and the West. That said, there is no Yahalpalanaya: corruption and nepotism have returned to pre-Rajapaksa levels; they remain rife. And tangible solutions to inter-ethnic fissures – justice for human-rights abuses, land restitution, demilitarisation, devolution of power – remain some way off.

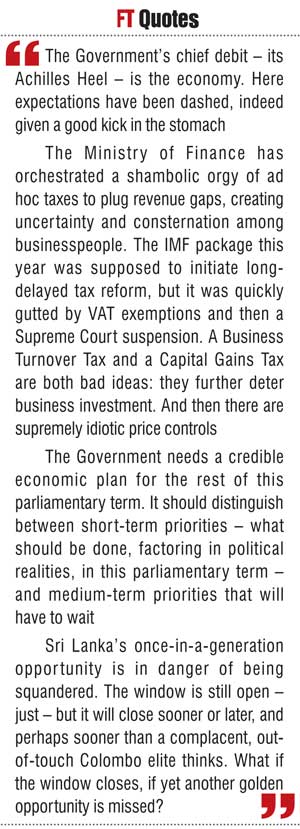

But the Government’s chief debit – its Achilles Heel – is the economy. Here expectations have been dashed, indeed given a good kick in the stomach. Regime change offered the best opportunity since 1977 to reform the economy, and to renew Sri Lankan society more generally. So far this opportunity has been squandered, following a dismal pattern since independence.

Economic diagnosis

What has gone wrong? I will start with macroeconomic policy. Since independence, successive governments have botched monetary and fiscal policies; they have been unable to control the taps of public spending and money-creation, generating an overflow of budget deficits, public debt, inflation, currency depreciation and balance-of-payments crises. This got worse under the Rajapaksas. The present Government has been equally unable to control these taps; indeed it has opened them further.

Take fiscal policy. Last year saw two disastrous budgets. There were unaffordable public-sector salary hikes and other new spending entitlements. New tax concessions further eroded the revenue base; tax collection came closer to total collapse. These measures increased reliance on debt, particularly foreign commercial borrowing, to finance recurrent and new expenditure.

The Ministry of Finance has orchestrated a shambolic orgy of ad hoc taxes to plug revenue gaps, creating uncertainty and consternation among businesspeople. No wonder they prefer to park their money in safe havens rather than investing in production and employment. The IMF package this year was supposed to initiate long-delayed tax reform, but it was quickly gutted by VAT exemptions and then a Supreme Court suspension. A Business Turnover Tax and a Capital Gains Tax are both bad ideas: they further deter business investment.

And then there are supremely idiotic price controls, first on tea and hoppers, and now on a longer list of goods. First the Government hammers consumers with high prices through inflation and import taxes – which hits the poor particularly hard since they spend more of their disposable income on essential items. Then it bludgeons producers with price controls. This is market-busting, an echo of Mrs Bandaranaike’s command economy in the 1970s.

Monetary policy has added fuel to the fiscal fire. The Central Bank printed money feverishly and kept interest rates low to finance Government debt and prevent an economic slowdown. But the result was a credit bubble, pressure on the Rupee and a deteriorating balance of payments. Now Sri Lanka has a new, eminently qualified Governor of the Central Bank. He understands the macroeconomic situation perfectly well.

The Central Bank’s imperative should be macroeconomic stability, starting with price stability – if necessary by counteracting fiscal-policy excesses. Dr. Coomaraswamy’s initial pronouncements are promising. The Monetary Board’s decision to raise interest rates is welcome. I wish Dr. Coomaraswamy Godspeed in restoring monetary stability. More generally, I wish him success in regaining  the independence and integrity of the Central Bank – which, of course, must extend to honest and transparent oversight of Treasury bond auctions.

the independence and integrity of the Central Bank – which, of course, must extend to honest and transparent oversight of Treasury bond auctions.

What about other areas of economic policy? The Government promised reforms to improve Sri Lanka’s competitiveness. The diagnosis is correct: Sri Lanka is stuck in a low-productivity trap; it must boost productivity for sustainable growth. But no reforms have happened so far – not to improve the domestic business climate, not to trade liberalise trade and attract foreign investment, not to reform state-owned enterprises, not on anything else.

Overall, it is clear this Government came to power unexpectedly and unprepared. It had no economic plan. The UNP drew up a basic economic blueprint ahead of last August’s parliamentary election, with a “social market economy” label. And the Prime Minister made an Economic Policy Statement last November, which struck the right tone but was brief and general. None of this has been translated into concrete plans and priorities for action.

What should be done?

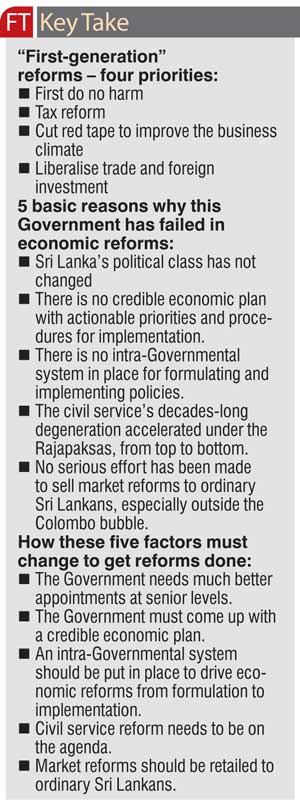

The Government needs a credible economic plan for the rest of this parliamentary term. It should distinguish between short-term priorities – what should be done, factoring in political realities, in this parliamentary term – and medium-term priorities that will have to wait. The latter are “second-generation” reforms that are too politically sensitive and intractable to tackle now. Privatising core SOEs and shrinking the public sector more generally, deregulating labour markets, land reform, getting the armed forces out of commercial activities – all fall in this bucket. But this still leaves sizeable “first-generation” reforms for the next three to four years. Here is my list of four priorities.

Political economy: How to reform

The economist’s habit is to diagnose the situation and then produce a wish-list of solutions – what I have just done. But that on its own is useless. Politics must be brought into play – indeed placed in the foreground. Then one has a more realistic appreciation of  problems and solutions. This is the world of political economy – “how to reform”, not just “what to reform”.

problems and solutions. This is the world of political economy – “how to reform”, not just “what to reform”.

I can think of five basic reasons why this Government has failed in economic reforms so far.

First, Sri Lanka’s political class has not changed. Old, established politicians have played musical chairs around the cabinet table, and kept a new generation of younger, competent professionals away from positions of power. This is not surprising: the old political elite – and their business cronies – have vested interests to defend. And so entrenched, unprofessional, bankrupt attitudes and methods persist.

Second, to repeat an earlier point, there is no credible economic plan with actionable priorities and procedures for implementation. Third, there is no intra-Governmental system in place for formulating and implementing policies – for evaluating policy options, coordinating across ministries and agencies, and seeing policies through to delivery. Rather decision-making chaos reigns – policy adhocery run amok, with different ministers and shadowy advisers saying different things and taking different initiatives off the cuff, constantly chopping and changing, and rarely following through.

Fourth, the civil service’s decades-long degeneration accelerated under the Rajapaksas, from top to bottom. It is not capable of implementing reforms effectively, but it is big enough to delay or block reforms that threaten in-house interests. And fifth, no serious effort has been made to sell market reforms to ordinary Sri Lankans, especially outside the Colombo bubble.

Combining these five factors is a recipe for decision-making stasis – no reforms, that is. It follows that each of these five factors must change to get reforms done. Simply designing and announcing a “plan” is just the start.

First, the Government needs much better appointments at senior levels. It needs an injection of fresh young blood – of uncorrupt, competent professionals. Second, the Government must come up with a credible economic plan. I hope the Prime Minister’s forthcoming statements on development priorities and a new trade policy will provide the right framework. Third, an intra-Governmental system should be put in place to drive economic reforms from formulation to implementation. Fourth, civil service reform needs to be on the agenda. Appointing clean, competent professionals to senior positions, including recruits from the private sector, would be the right start.

Fifth, and finally, market reforms should be retailed to ordinary Sri Lankans – not just the Colombo elite and upper-middle-class professionals, but also the secondary-city and small-town bourgeoisie, the urban working class and rural heartlanders. This is where cohabitation between the President and Prime Minister, and a National Unity Government, however unwieldy, should come in handy.

So far cohabitation has got stuck in short-term tactical posturing on all sides. But it could be otherwise. The President and Prime Minister have different backgrounds, strengths and weaknesses. Among politicians, the Prime Minister is the country’s leading policy thinker by far. But the President, like President Rajapaksa before him, can connect intuitively with small-town and rural Sinhala-Buddhist Sri Lanka. There are other politicians in both the SLFP and UNP who have this ability. Surely these skills should be combined and harnessed. Sri Lanka is a complicated democracy. Of course it needs decisive leadership, but it also needs a political culture of persuasion and consent for reforms to succeed.

Conclusion

Sri Lanka’s once-in-a-generation opportunity is in danger of being squandered. The window is still open – just – but it will close sooner or later, and perhaps sooner than a complacent, out-of-touch Colombo elite thinks.

What if the window closes, if yet another golden opportunity is missed? I foresee two negative scenarios. The less-worse one is that Sri Lanka will continue to drift, performing far below its potential, depriving ordinary people of the life-chances they deserve, muddling along in lazy, sloppy mediocrity.

The more malign scenario is that the present situation will spiral backwards. A macroeconomic crisis might be the catalyst. Or it could result from popular frustrations – no new investments, no new jobs, no change – boiling over. Then, in the Sinhala-Buddhist heartland, people might yearn again for a Big Man, a Rajapaksa or someone else, to ride in and clean house, sweeping away liberal rights and democratic niceties with his authoritarian broom. They could vent their frustrations at the minorities who got President Sirisena and a UNP-led Government elected. Down the line, Sri Lanka could be back in the exclusive embrace of China, taking its leave once again from its civilisational friends in India and the West.

This is why the economic stakes are so high, and why market reforms are so urgent. Aren’t Sri Lankans capable of something better than the status quo? A few months ago, after a talk I gave, a Colombo businessman remarked, “Surely we Sri Lankans aren’t as bad as this.”

(The author is Chairman of the Institute of Policy Studies, Sri Lanka, and Associate Professor, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore.)