Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Friday, 10 February 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Dharisha Bastians

Reporting from Batticaloa

Mohammed Ibrahim, a 40-year-old Kattankudy businessman, looked up after the gunfire stopped. Dozens of men, who had been kneeling, face down in prayer just like him only moments ago, lay unmoving around him.

On 3 August 1990, Tiger cadres wielding machine guns and hand grenades stormed into two mosques in Kattankudy in the Batticaloa District during Friday night prayers and opened fire. The two mosque attacks claimed the lives of 147 men; nearly all of them shot in the back as they prayed.

For Sri Lankan Muslims living in the embattled north and east, 1990 was a brutal year. Two months after the Kattankudy mosque attack, the LTTE forced nearly 75,000 Muslims living in the north out of their homes overnight in October 1990, in a vicious act of ethnic cleansing.

As the conflict raged, the LTTE grew deeply suspicious, and seeing the Muslims as having become spies for Government troops, they turned their guns on the main minority community living in the Tamil-majority war-zone. The Tigers attacked mosques and burned Muslim homes and shops, sowing deep mistrust between the Tamil and Muslim communities that live cheek by jowl, particularly in the Eastern Province.

Twenty-seven years later, the memory of the Kattankudy mosque attack still looms large in the Muslim majority town. Kattankudy residents never cemented over the bullet holes on the walls of the mosque, and the pockmarked interior remains a grim reminder of the town’s tragic history.

Relations between the Tamil and Muslim communities have since healed considerably, but underlying tensions are far from fully disappearing. The Tamil community and their representatives also view Muslims with suspicion, because of their perceived tendency to align themselves to the Government and lobby Colombo separately on their issues. Economic disparities between the two communities are also acute, Tamil political representatives say.

A few kilometres away from Kattankudy town, the Tamil People’s Council will lead its second Eluga Tamil (Rise, Tamil!) demonstration at 9 a.m. today, led by Northern Province Chief Minister C.V. Wigneswaran. The Batticaloa Eluga Tamil rally was originally scheduled to be held on 21 January but postponed twice, due to “Wigneswaran’s unavailability”, as the organisers put it. TPC Co Chair Vasantharajah told Daily FT the organisers were expecting a crowd of about 10,000 people. The Northern Chief Minister was expected to attend, he said.

Intended to highlight grievances of Tamils living in the north, the first Eluga Tamil rally in Jaffna in September 2016, was a study in the rise of reactionary Tamil nationalism and sparked a significant backlash from Sinhalese nationalist forces operating in the south. The rally drew on the memory of the LTTE’s Pongu Tamil (Awake, Tamil!) demonstrations during 2002-2004 ceasefire years and featured anti-Sinhala and anti-Buddhist slogans. A major criticism of the Jaffna rally was that it was focused only on issues facing the Tamil people and completely ignored the grievances of the Muslim population living in the north.

The TPC attempted to repair this omission in the weeks leading up to the rally in Batticaloa, which is a much less homogenous region than many parts of the north. Organisers invited Muslim community leaders and politicians for discussions, and tried to drum up support for the demonstration which they claimed would highlight the grievances of all Tamil-speaking people in the east.

But the war-time history of communal tensions in Batticaloa and the prospective rise of Tamil nationalism in the region were making Muslim leaders in Kattankudy uneasy weeks before the rally. Still smarting from being ignored during the TPC’s northern demonstration, community leaders in Kattankudy dismissed the TPC outreach ahead of the Batticaloa rally as an “opportunistic” attempt to obtain Muslim support for key Tamil demands – especially the re-merger of the Northern and Eastern Provinces.

“The TPC takes up Muslim issues opportunistically,” says A.L.M. Sabeel, who is General Secretary of the Federation of mosques and Muslim institutions, Kattankudy. “In 1990 the LTTE evicted us. Always saw us as the “other”. Now they use ‘Tamil speaking people’ when they want our help. For Muslims, the Tamil language is just a tool we use to communicate, it does not mean we are the same as the Tamils,” Sabeel explains.

Muslim community leaders in the east are acutely aware that their concerns played no part in the Jaffna Eluga Tamil rally. The resettlement of Muslims displaced from Jaffna and Mannar since 1990 and the ongoing Wilpattu controversy should have featured in the demands of the Jaffna demonstration, if the rally was a genuine effort to highlight issues facing the Tamil-speaking people, office bearers at the Mosque Federation told Daily FT.

This has caused deep resentment, Sabeel says, because Northern Muslims voted en masse for Chief Minister Wigneswaran in the 2013 provincial elections. “We thought he was an educated man, who would address Muslim issues. But we are so disappointed,” he admits.

Chief Minister Wigneswaran’s recent call for support for the Eluga Tamil rally in the east has done little to allay those fears. While seeking public support ahead of the Eluga Tamil demonstration in Batticaloa, Wigneswaran glossed over LTTE crimes as he urged Muslims to support the rally. He said Tamil speakers across religions in the east had lost land and language rights as a result of systematic Sinhalese colonisation and called for a “united” North Eastern Province in which Tamil speakers could live in peace.

Wigneswaran admitted that Muslims had “apprehensions” about their safety in a Tamil-majority north-east in “view of some past happenings and other reasons”, stopping short of naming the crimes committed against Muslims in the east by the LTTE.

Muslim community leaders in Batticaloa are convinced these overtures by Wigneswaran and his TPC are solely aimed at winning Muslim support for re-merger of the two provinces.

“In the east, they want to push for re-merger of the two provinces,” says Sabeel, “so they are trying to negotiate with us.”

Eastern Muslims completely reject the north-east merger, the Federation says. They believe a merger will allow Tamils to dominate the Eastern Province, which is home to over 500,000 Muslims who make up 36% of the region’s population, Sabeel explains. “A merger will strengthen the Tamils and oppress the Muslims. That’s what happened in the past,” he claims.

Tamil politicians claim that the distrust between the two communities is mutual. Eastern Provincial Council Minister and ITAK General Secretary K. Thurairajasingham said Muslims had been dominating in the east since the two provinces were de-merged in 2006.

“Muslims are concerned that a re-merger would bring down their population percentages in the whole region,” the TNA politician claimed. Thurairajasingham said. Tamil representatives were wary of their Muslim counter-parts because Muslim political parties have a “tendency to get favours” from the Government in Colombo.

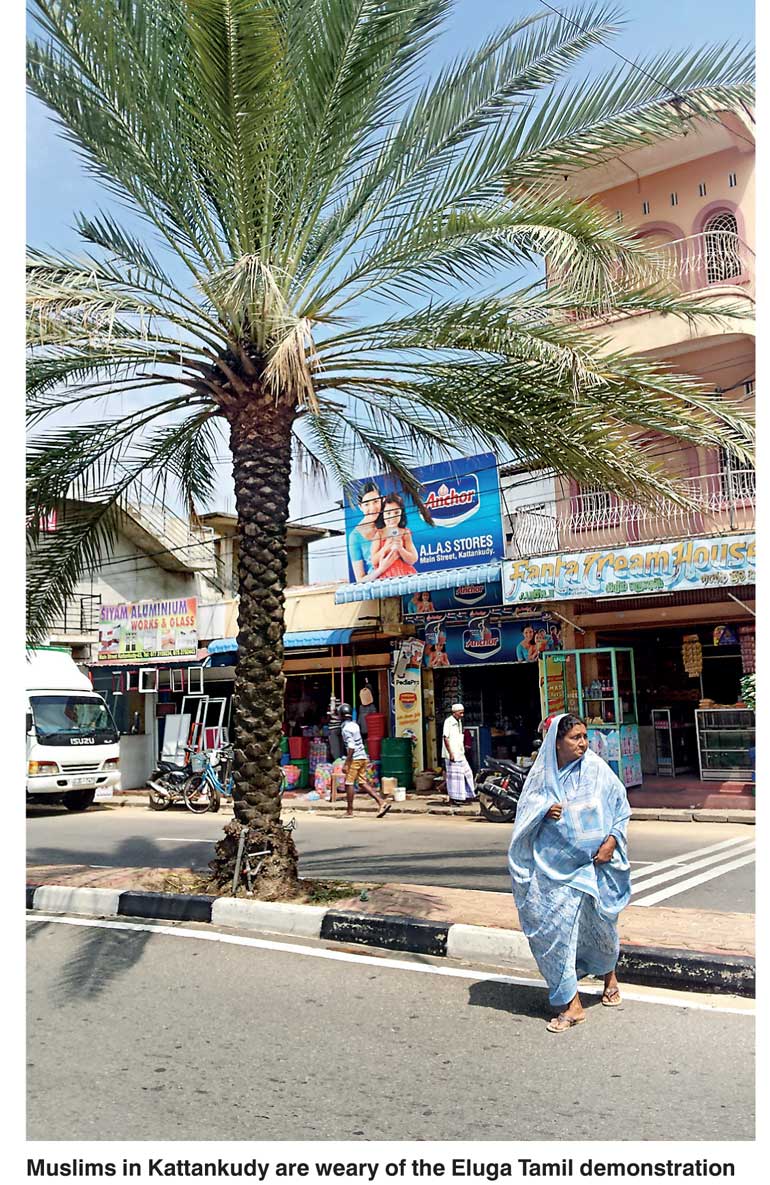

While the two Tamil speaking communities mostly co-exist peacefully, Tamils and Muslims living in Batticaloa hold fast to separate cultural and religious identities. Only a few minutes’ drive away from the predominantly Tamil Batticaloa town, the landscape alters drastically on the approach to Kattankudy.

Sixty-seven date palms sway in the breeze on an island on the main street, oddly out of place with other foliage in the region. Once a year, during the holy month of Ramadan, Kattankudy residents reap a harvest of dates.

“Just like the Tamils and the Sinhalese, we are a distinct community,” says the Mosque Federation official. “We completely reject the merger. North should be north. East should be east.”

Community activists point to a creeping radicalisation of the Muslim community in the east that is also contributing to a lack of integration between the communities. The Muslim population of the east is growing increasingly conservative and retreating further into settlements in which their way of life tends to dominate.

Sabeel admits there has been such a shift in the east in recent years. “Those days, Muslim women wore the sari and covered their heads with it. Now there are more women in Hijab – but we feel this is respectable and safe for our sisters and daughters,” he explains.

The Mosque Federation official denies that Middle Eastern countries that heavily fund mosques and religious schools in the area impose conditions on the Muslim population living in the Eastern Province. “But they do encourage covering and certain cultural habits,” he admitted.

K. Kandheepan, a Tamil community organiser who works at a disability rights NGO, explains that while Muslims living in the east fear re-merger of the Northern and Eastern Provinces, Eastern Province Tamils share some of those concerns. “There are fears of northern dominance within the Tamil community itself,” the community worker explains.

Tamil residents in the east believe that the leadership of the Tamil National Alliance (TNA) which dominates politics in the north and east is extremely Jaffna-centric. Kandheepan is also critical of the TNA’s ethnicised political approach, which tends to ignore minority communities living in the north and east. “There is very little articulation of Muslim concerns in the TNA agenda,” he asserted.

The Tamil community worker worries that nationalist mobilisation like Eluga Tamil, which comes at a time when Government commitments to constitution making and reconciliation appear to be waning, could jeopardise an already fragile and uncertain process.

“The rally will kindle a lot of emotion, but will it have any real impact on the issues?” Kandheepan wonders.

Sathasivam Viyalendran, a TNA lawmaker representing Batticaloa, says he is a belated proponent of the Eluga Tamil movement but believes the agitation is necessary. “It’s two years since the 2015 elections. A little bit of land has been released but have any real problems been solved?” he says.

In addition to land issues, disappearances and concerns about ex-combatants and war widows, war-affected Tamils were faced with a host of new challenges, the Eastern Province politician says. According to Viyalendran, the settlement of people from the south in the east and Buddhist religious symbols emerging all over the region were issues. But these were compounded by socio-economic issues, including alcoholism that had taken hold in the region, a high suicide rate and predatory micro-credit companies offering inflationary loans that were further impoverishing vulnerable women and communities.

“People come to Batticaloa, see the scenic town and say how beautiful it is. But travel inside, a few kilometres from the coast, and they will see how a community is being destroyed,” the EPC Member explains. Economic disparity between the Tamil and Muslim communities is acute, he claims. “Muslim areas look like Europe, Tamil areas look like Somalia.”

Viyalendran says that in the face of all these challenges the TNA leadership was asking politicians in the area to remain silent. “But how do we face the people?”

Eluga Tamil is only an effort to highlight genuine concerns and pressure the Government, the eastern politician says. While demonstration will mainly highlight Tamil concerns, it will also seek to bring out issues facing the Muslim and Tamil communities, he vows. But he warns that patience is wearing thin in the east. At this rate, Viyalendran says by the time a solution is found, there will be no Tamils left in the region.

“All we are saying is, give us what we want, give it to us without delay,” he said.

But for Sabeel and other Muslims, Eluga Tamil is a representation of a more fundamental problem that Tamils, who dominate large parts of the north-east have never addressed. “Pongu Tamil happened because Sinhalese oppressed the Tamils. But what did Tamils do? They oppressed Muslims. The problem with the Tamils is that they never recognised problems of marginalised people in their own community or the Muslims with whom they live side by side,” he says.

Frustration and discontent have simmered in the Eastern Province in the absence of real attention to the issues, says S. Amara, a community worker in the region. The timing of the demonstration is bad, says Amara, but as a resident of Batticaloa who works closely with war-affected women and youth, she understands why it is happening now. The fear for eastern residents is that demonstrations like Eluga Tamil could contribute to the closing up of the little democratic space that has opened up in the region since 2015.

“With these protests, the discourse shifts from genuine grievances of the war affected. The South reacts badly and begins to worry about a resurgence of the LTTE. That could result in a return to surveillance and harassment in the former conflict zones,” Amara explains.

Kandheepan says that the post-war context is vastly different from the Pongu Tamil years. There are serious questions about whether this type of nationalist mobilisation is necessary at this time, the community organiser explains. “Whether in the north or south, nationalist mobilisations are not unifying,” he says. “They tend only to divide people.”