Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Wednesday, 12 April 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By T. Rusiripala

The Constitution of Sri Lanka started with the Soulbury Constitution consisting of The Ceylon Independence Act and The Ceylon Orders in Council, 1947. It provided for a parliamentary system of government and included a special Article (29 {2}) to safeguard minority rights. In addition to the Parliament there was an Upper House similar to the UK, a Senate.

Parliament consisted of 101 members, all of whom except six to be nominated by the Governor General were elected under universal suffrage. This constitution underwent several changes from time to time but all attempts made by the legislators to revise it to suit the local conditions ended up in failure. The first noteworthy major change to this Constitution was effected in 1971 by the abolition of the Senate.

The new Government of Sirimavo Bandaranaike that was formed as a coalition of all progressive political parties drafted a new constitution by converting the entire Parliament into a constituent assembly in 1972, giving birth to a unicameral type of legislature and changing the Parliament to a National State Assembly. The name Sri Lanka was substituted in place of Ceylon, how our country was then known to the world. Many new features were associated with this change such as the enshrinement of Fundamental Rights as part of the Constitution.

This Government was defeated in 1977 bringing J.R. Jayewardene into office as the Prime Minister of the country with his party the UNP. The controversial Constitution which is the centre of focus today was brought in by the UNP which enjoyed an unprecedented five-sixth Parliamentary majority. The Prime Minister became the first Executive President under this constitution.

Many opinions were then expressed by opposition politicians and others about the possible dangers that certain provisions of this Constitution would bring about in the future. Some declared that the Constitution had paved the way for an elected dictatorship. The many things that transpired and were orchestrated subsequently proved beyond doubt that it created an elected executive having untrammelled power.

Due to the way it was formulated it was an impossible task to undo it. It was only a government with by far an absolute majority in Parliament that could even bring any amendment to it. The regime that created such a monstrous piece of legislation truly usurped powers under it to prevent any challenge to the hegemony of the UNP for the next seven years.

The irony of this exercise was a clear violation of every known norm of democracy in the name of safeguarding democracy. One could see many instances of compromising the integrity of the Legislature and the Judiciary involved in acts of blatant political victimisations perpetrated during this period.

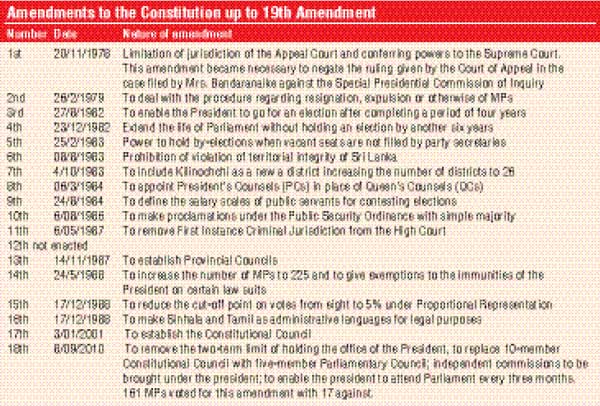

The Government freely used the powers it derived with the five-sixth majority in Parliament to amend the Constitution as and when it desired. An examination of the amendments will clearly establish the purpose such amendments served and for whose benefit. A schedule of the list of amendments made to the Constitution since 1978 is produced here separately for the easy reference of the readers. The Constitution can be amended by a two-thirds majority in Parliament with regard to matters that do not require a further approval at a national referendum.

Most revolutionary reform

Most revolutionary reform

The most revolutionary reform to the Constitution was brought about under the last amendment, the 19th, which was the result of a promise given by the new President Maithripala Sirisena as an election promise during his campaign to defeat the then incumbent Mahinda Rajapaksa. This amendment involved several favourable and much-desired features.

The 18th Amendment to the Constitution which gave extraordinary powers to the President to contest beyond the accepted two terms period was repealed under the 19th and it also restored several rights under the 17th Amendment which remained unfulfilled. This amendment paved the way to the establishment of independent commissions under the provisions of the Constitutional Council. The term of office of the President was reduced to four years and removed several articles granting immunity to the President.

On the whole the 19th amendment brought many changes by diluting certain excessively harsh powers vested in the executive presidency. It is an irony of history that a Parliament which voted for the 18th Amendment to increase the draconian powers of the Executive President voting again during the same term to reverse those under a new president! In a 225-member parliament, 215 voted in favour of the 19th Amendment on 28 April 2015 with only one member against.

During the presidential election of 2015, and the Parliamentary election that followed, many pledges were given by the UNP towards the restoration of democracy and good governance and proposed a new constitution to control the executive powers of the president politically by the parliament. They also proposed to abolish the preferential system of voting and reduce the life of Parliament to five years. The rights to information and freedom of expression were also among the principal changes envisaged.

The 100-day Government failed miserably to accomplish the promises given except for certain piecemeal changes mainly on the issue of the President’s prerogative to dissolve Parliament. The Proportional Representation and the preferential system of voting which were the main expectations of the people happened to stay on as the legislators were unwilling to change.

People were desperate to see the dawning of a period for selecting those who can be truly called legislators of the country instead of corrupt and unwanted elements who get thrown into the House under the existing system. It was not difficult to understand the ostensible moves under which undesired divisions and differences were created as deliberate sabotage. Those decision makers seem to be more complacent to continue with the nincompoops instead of genuine leaders interested in the future of the country.

In such a context can we believe that the proposed constitutional changes are for the betterment of the country? Or is it a further exercise to guarantee and strengthen the survival of the present clan? Do we see any semblance of a desire to relinquish power or authority in the public interest associated with any of these proposals? Are they genuinely interested in reducing the paid number of Cabinet Ministers? Or are they not there to circumvent any principle to accommodate a super jumbo Cabinet in order to remain in power?

We must learn to judge the people by their deeds and not by their rhetoric. Therefore the social forces, intellectuals and free-thinking people have to start a process of inculcating new thinking in new directions. A way should be shown away from what is shown to us traditionally by the politicians who over a long period of time have taken their turn of the tide, changing from coming in to going out or vice versa.

Are any of those who propagate the idea of a new constitution thinking of ways and means of reducing their own power base or their undeterred rights conferred on them to look after themselves above the country’s interests? Is it not what they are doing now? They use the political power to buy over people offering ministerial portfolios. They offer innumerable perks envied by people to themselves in their quest to fulfil their requirements. They fatten their purses well and truly with no pain of mind.

Can a constitution guarantee good governance? May be they can remove certain draconian interventions. But even under the best of constitutions, corruption can exist. For good governance, justice and fair play, we need good legislators. To select good legislators we have to have a good system in place.

A well-known authority on the (unwritten) British Constitution, Walter Bagehot, said: “The cabinet is a board of control chosen by the legislature, out of persons whom it trusts and knows, to rule the country.”

Now when we examine how these persons are chosen currently, we can see there are so many limitations and issues. When a new party is elected into power, the Prime Minister has to invariably choose from the lot that have come in. He may not have the best wanted for the job. In the case of a business it is different. When the CEO wants a person with a certain background for a particular job, he can go for an executive search. He will never be handicapped for want of talent.

But in the case of the existing system of government, someone among those who have not been elected for their record either as a manager or leader has to be made a Cabinet Minister! In a way it is very amazing how a country runs under such a set up. Fortunately the world has seen these weaknesses and innovated rescue bodies such as the IMF/World Bank to assist not only financially but even by giving proper advice.

In most countries, they have developed systems to draw their cabinets from non-Parliamentarians. Except in Britain and Ireland, the 20+ member countries of the European Union do not deem it necessary to draw their Cabinet from the Parliament. In these countries the ministers either should not be MPs or even if they happen to be, it does not have to be so. In one way it helps to separate powers better than when MPs become ministers.

The Cabinet of Ministers has an executive function. If they are MPs they are members of the Legislature too. So there is an overlapping in the role. It is best that the three roles of the government – Legislature, Executive and Judiciary – be separate. If all three powers are vested in one body, it becomes a dictatorship. In other words, an elected dictatorship.

We have seen how our Judiciary operates as an independent arm. Why cannot the Executive too be made to stand alone? But one can be certain that no Parliamentarian will ever like this. Because all of them are dreaming to be upgraded as ministers and will do anything for that. If the ministers are from outside the Parliament, they can be made accountable to it and this will give an enforceable right over them to the Legislature.

The ministers today are running round to look after their constituencies and electors while attending to their ministerial responsibilities. Both functions therefore suffer due to limitations of time. Politics has become a career than a service. Politicians have be loyal to the party leader, be guided by party discipline, etc. Why should not a minister be freer to exercise his authority true to his conscience rather than being dictated by the party leader? If they are drawn from outside, they will have longer periods to serve and adhere to a clear policy line and work independently with a longer-term view. They also do not have to be concerned about elections or getting elected.

It is time that we look forward to something meaningful if a new constitution is to be brought in. Our past experiences with the constitution makers caution us to beware!