Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Monday, 29 May 2017 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

New Finance Minister Mangala Samaraweera officially assuming duties at the ministry – Pic by Pradeep Pathirana

New Finance Minister Mangala Samaraweera officially assuming duties at the ministry – Pic by Pradeep Pathirana

Promise to continue with economic reform program

The new Minister of Finance, Mangala Samaraweera, who assumed office at the ministry without much fanfare, has testified to his humbleness when he made his maiden speech in Parliament. He had said that the shoes he had to wear now had been “much too big for him to wear”, a testament to the seriousness of the job at hand (available at: http://www.ft.lk/article/617417/Mangala-promises-to-rebuild-economy--meet-development-goals ).

Yet he had given a solemn undertaking that he would “commit himself to implement the economic reforms needed to save the country from the debt trap it is in.” He had reiterated, quite correctly, that it would be the private sector that would propel the economy and that would be the focus of his policy.

Samaraweera had also mentioned the names of some of his predecessors who, according to him, had had high political stature, compared to his own naivety in the field as he had humbly admitted. Of the names he had mentioned, not all of them had been great ministers of finance with respect to self-discipline or foresight. Like any ordinary lay person, they were also not free from human frailties and, therefore, he should not seek to emulate all of them.

However, of them, Dr N.M. Perera, known as NM, who held the portfolio from 1970 to 1975, should serve as a guiding light for him when he has to deal with his main economic advisor, the Central Bank.

As this writer had mentioned in a previous article in this series (available at: http://www.ft.lk/article/614940/CB-Annual-Report-2016--Bold-in-critical-analysis-and-proactive-in-policy-recommendations), the job of the Central Bank has been to give its advice to the Government impartially and objectively, taking an apolitical stance. NM had highly valued it as he had indicated to the senior staff of the bank when he had addressed them at a function held in 1971.

According to a report in the Ceylon Daily News reproduced by the bank in its 60th Anniversary Commemorative Volume, NM was reported to have said that the bank should make “independent reports on economic subjects to the government and not reports (that) merely suit the political complexion of the government in power” and “he would value reports (of the bank) made dispassionately and objectively”.

Thus, a Finance Minister with foresight and wisdom should not get offended when the Central Bank makes a critical analysis of the prevailing state of the economy. Indeed, he should welcome such critical analyses because they allow his Government to take remedial measures before the situation becomes too critical to handle.

There had been two other occasions where NM had demonstrated his self-discipline as a politician of stature when he dealt with the Central Bank. This writer recalls that in 1973, NM’s private secretary, ignoring the protocol where the Governor of the Central Bank should be addressed only by the Minister, had sent a letter to Governor H.E. Tennakoon requesting him to submit the lists of candidates to be appointed to the bank for the Minister’s approval.

Governor Tennakoon, the senior-most civil servant that he was, got his Director of Establishments to write back to him that the Monetary Law Act did not permit the Minister to make such approvals and that matter should be brought to the notice of the Minister. NM did not bargain for that information after that.

The other occasion was when NM had sent a directive to the Central Bank not to pay a bonus to employees on the grounds that it  was not a profit-making institution. His claim that the bank was not a profit-making institution was correct; yet what was paid to Central Bank employees was not a bonus based on profits but an incentive payment called Annual Special Payment linked to their attendance. Therefore, Governor Tennakoon ignored NM’s directive and went ahead with making the payment to employees. After it was clarified to him, NM did not make a fuss about it.

was not a profit-making institution. His claim that the bank was not a profit-making institution was correct; yet what was paid to Central Bank employees was not a bonus based on profits but an incentive payment called Annual Special Payment linked to their attendance. Therefore, Governor Tennakoon ignored NM’s directive and went ahead with making the payment to employees. After it was clarified to him, NM did not make a fuss about it.

Hence, NM had set some precedents for Samaraweera to follow as a Minister of Finance.

Samaraweera says that he is new to the subject of finance. But that position is not quite correct. He had functioned as the Deputy Minister of Finance for three years during the Presidency of Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga from 1998-2001.

Prior to that, he had proved himself as a bold reformer by privatising Sri Lanka Telecom and thereby paving the way for modernising the country’s telecommunication system. With that, the long waiting lists for landlines which had been the curse of all telephone users prior to 1996 have been made things of the past. He met with fierce opposition when he embarked on the project from all quarters: his own Cabinet colleagues, opposition from the UNP, trade unions and the media.

Yet, he was able to successfully manage them and reach his final goal. With that track record behind him, the country can place confidence in him for doing a successful job when he announced in Parliament that he would commit himself to implementing the needed economic reforms.

Without economic reforms Sri Lanka has no future and would be destined to remain forever a stagnating agro-based economy with low productivity, poor human capital and inferior technology.

Central Bank reports today are candid and free from political bias

Hence, Samaraweera has a Herculean task ahead to rescue the economy from the depths to which it has fallen. Despite the claims made by his immediate predecessor, Minister Ravi Karunanayake, that he had rescued the country from the economic depths, Sri Lanka’s economy today is in a sorrier state than before. Samaraweera has to read only the first chapter of the Central Bank Annual Report for 2016 (available at: http://www.cbsl.gov.lk/pics_n_docs/10_pub/_docs/efr/annual_report/AR2016/English/content.htm) and the recent press statement of the bank on the performance of the external sector of the country during the first two months (available at: http://www.cbsl.gov.lk/pics_n_docs/02_prs/_docs/press/press_20170525e.pdf ) to gain a sense of the real situation.

The first chapter in AR 2016 starts with a candid admission of the poor performance of the economy during 2016 on all fronts.

Growth has slowed down from 4.8% in 2015 to 4.4% in 2016; per capita income which has increased in rupee terms from Rs. 522,355 to Rs. 558,363 has fallen in dollar terms from $ 3,843 to $ 3,835 due to the depreciation of the rupee; inflation, measured in terms of the Colombo Consumers Price Index, has accelerated from 2.2% in 2015 to 4% in 2016; to make matters worse, core inflation, which is free from weather or price control effects on food items and, therefore, measures the level of the money aggregate demand is on the increase; though the budget deficit has been contained at 5.4% of GDP in 2016, the central government debt has increased from 78% of GDP in the previous year to 79% of GDP in 2015; exports have declined, the trade deficit has expanded and the balance of payments has recorded a deficit for the second consecutive year; the rupee has been under pressure for depreciation, while foreign reserves have declined from $ 7.3 billion at end-2015 to $ 6 billion at end-2016.

There had been further erosion of foreign reserves during the first four months of 2017, bringing the gross amount of official reserves to $ 5 billion as at the end of April 2017. After raising $ 1.5 billion through the issue of sovereign bonds in early May, the Central Bank has been able to add about a billion to reserves, but Samaraweera should not allow himself to be misguided by such reserve build-ups through borrowed funds. They go against Samaraweera’s own plan to rescue the country from the present debt trap.

Sri Lanka’s exports have been falling since January 2015. This has been repeated in the first two months of 2017 according to the latest press statement of the bank on the country’s external sector performance. Accordingly, exports have fallen by nearly 7% during January-February 2017 compared to the corresponding two months in 2016.

To make matters worse, imports have increased by 13%, causing the trade deficit to expand further. The new trade deficit figures are alarming and if they continue to persist during the balance part of the year, it will reach a staggering level of over $ 10 billion in 2017 as against a trade deficit of $ 9 billion in 2016.

In the first two months of 2017, the overall deficit in the balance of payments had amounted to $ 258 million. The country could eliminate this deficit only by making additional foreign borrowings but they would exacerbate the present external debt build-up.

This is bad news that points to a worsened macroeconomic crisis in the country. Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, in the economic policy statement he presented to Parliament in October 2016, opined that Sri Lanka needs to have a minimum annual economic growth of 7% in the next 30-year period. If Sri Lanka succeeds in maintaining this growth rate, it will enable the country to join the rich country club by 2045, within a single generation. This is an ambitious target since the annual growth which Sri Lanka has maintained over the entire post-independence period has been around 4.4% on average.

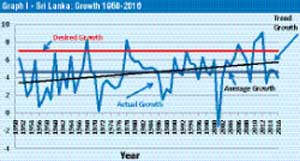

As Graph I shows, the annual growth has been highly volatile in the past and the country has been able to exceed the minimum required rate of 7% only on five occasions. Even then, that had been a way apart from each other.

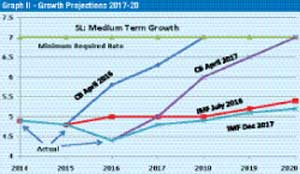

In the medium term up to 2020, as Graph II has shown, the best predictions made with respect to growth have been around 5% which is far below this minimum required rate.

The longer the country is trapped in low growth, the more difficult for it to reach its goal of becoming a rich country within a single generation. Hence, Samaraweera has to act at double speed, coordinating his work with other Government agencies and the private sector, to push the economy to a high-growth path and sustain it for a long 30 years.

Countries that have faced worse economic crises have come out of them by using prudential policy packages aiming at future prosperity rather than short-term political expediency. For long term economic prosperity, Sri Lanka has to make it easier for people to do business, improve its competitiveness, invest heavily in both human and physical infrastructure, improve productivity and efficiency in government services and have access to foreign markets.

All these require Sri Lanka to introduce economic reforms but reforms are painful and costly. Hence, in the past, all Finance Ministers, including Samaraweera’s immediate predecessor, chose the easy path of seeking short-term political expediency sacrificing long-term growth objectives. Now Samaraweera has to make this hard choice which is politically unpalatable but necessary for long-term prosperity.

An important requirement for Samaraweera to do this job has been that all financial institutions should be correctly placed under him. Thus, institutions which have been listed under different ministries but legitimately should come within the Ministry of Finance should be returned to that Ministry.

The financial institutions involved are the Central Bank, state banks, Securities and Exchange Commission, Employees’ Trust Fund and the Sri Lanka Insurance Corporation. Without them under him, it is unthinkable that he would be able to introduce the reforms which the Government expects him to do.

Then, he and the Governor of the Central Bank should speak the same language with respect to macroeconomic policy and economic policy reforms.

A grave mistake committed by his immediate predecessor in this regard was the attack on the Governor and the senior officers of the bank in public, thereby undermining their position. Such attacks may be appealing to the local voter-base but will not be taken kindly by those outside Sri Lanka who have an interest in investing in the country.

A Finance Minister stands to gain if he works closely with the Central Bank. The Central Bank has a vast build-up of human talents and skills and those skills should be effectively used by Samaraweera to design and implement the economic policy reform program.

This writer recalls that during the previous Ranil Wickremesinghe administration of 2002-2004, the Central Bank was at the forefront of the economic policy reform program implemented by the Government. Thus, Samaraweera should use the resources within his reach in the first instance and look for resources from external sources only to fill the gaps.

Samaraweera’s success as Finance Minister in bringing prosperity to Sri Lanka will, therefore, depend on his ability to move forward with foresight, self-restraint and self-discipline.

(W.A. Wijewardena, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected]).