Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Friday, 27 October 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Ninety years ago, on 13 November 1927, the Donoughmore Commission was set up to bring forth a worthy change that would satisfy all parties in Sri Lanka. The end result was universal franchise amid a fully-functional democratic structure.

Ninety years ago, on 13 November 1927, the Donoughmore Commission was set up to bring forth a worthy change that would satisfy all parties in Sri Lanka. The end result was universal franchise amid a fully-functional democratic structure.

Lord Donoughmore, who was instrumental in bringing forth that change, was renowned for another reason. He was a liberal peer who championed the cause of women’s rights to university education. It was his ambition to introduce universal suffrage to enable women to vote in elections. Until the Donoughmore Constitution came to be, neither the Colebrook Constitution of 1833 nor the Crew-McCullum Constitution of 1910 or the Manning Constitution of 1920 enabled women’s representation.

The right to vote prior to the Donoughmore Constitution was limited to only wealthy and educated males above the age of 21 years. They comprised a mere 4% of the Sri Lankan population. Women did not have the right to vote at elections at all.

Lord Donoughmore called on the commissioners to recognise female suffrage and eventually universal franchise became a reality in Sri Lanka. Everybody above the age of 21 years was permitted to vote. Sri Lanka became one of the first Asian countries to grant voting rights to women. Adeline Molamure, daughter of J.H. Meedeniya and wife of Alfred Molamure, became the first representative of women in politics. However, despite the monumental victory which was realised in 1931, the democratic system of Sri Lanka continues to suffer even today.

The 1931 Donoughmore Constitution extended territorial representation and established a State Council. There was an Executive Committee system too, and through it a Cabinet was given authority to rule. The State Council had 61 members of whom 50 were elected on a territorial basis. Of the remaining 11, the Chief Secretary, Financial Secretary and the Legal Secretary were considered officers of the state. The other eight were nominated by the Governor.

The electoral system was the First Past the Post system. Under this system, the electoral boundaries are drawn up and the highest grosser of votes within that electoral boundary wins.

The State Council comprised seven executive committees for Home Affairs, Agriculture and Lands, Local Administration, Health, Transport and Labour, Education and Industry and Commerce. It was the first step towards a greater beginning for Sri Lankan democracy. The Donoughmore Constitution also made recommendations to have members of local authorities elected. Hence, the Urban Councils Ordinance of 1939 was born. At a much later stage, the Town Councils Ordinance of 1946 and the Municipal Councils Ordinance of the 1947 was also enacted.

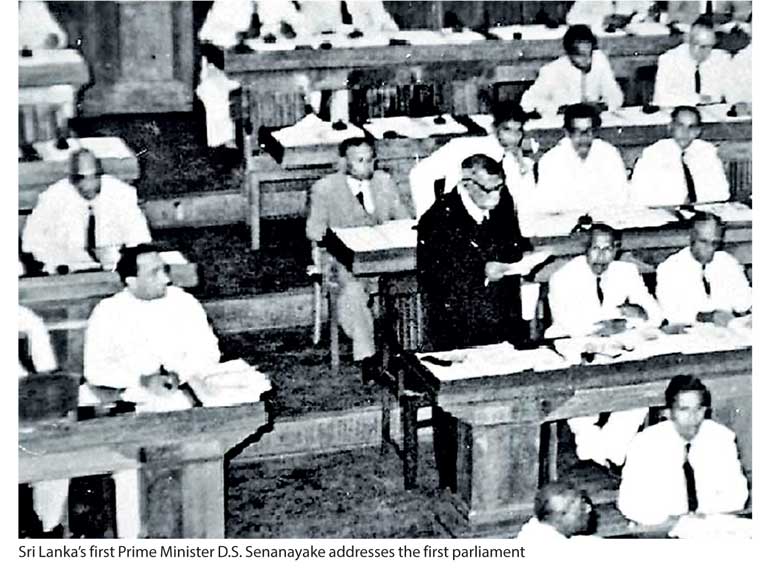

The Donoughmore Constitution was indeed the stepping stone for democracy in Sri Lanka, and the Soulbury Constitution which followed 16 years later built on that foundation a concrete democratic structure. The Soulbury Constitution is essentially special for Sri Lankans as it guaranteed independence from British rule. It was largely influenced by Sri Lanka’s first Prime Minister D.S. Senanayake with the support and advice of Sir Ivor Jennings.

This year on 3 September we marked 70 years of Parliament-based democracy in Sri Lanka. In 1947, the Soulbury Constitution came into force. The position of Governor was abolished and a new position of Governor General was introduced with limited rights over the country. Sri Lanka inherited the Westminster-styled bicameral parliamentary system with a House of Representatives and a Second Chamber (also known as a ‘Senate’).

The House of Representatives was to have 101 members, of which 95 were to be elected through universal franchise, and six members were to compulsorily represent minority communities in the country.

The Second Chamber/Senate had 30 members, 15 of whom were to be elected from the House of Representatives in Parliament, while the other 15 members were to be nominated by the Governor General on the advice of the Prime Minister.

Of the 101 members, only three of them turned out to be women in the first election under the Soulbury Constitution. The 1952 Elections introduced only two women. The subsequent elections returned only four women and three women respectively. Despite the poor numbers, women did eventually rise to great power, especially with the likes of Sirimavo Bandaranaike becoming the very first woman Prime Minister of a country in the world.

Under the Soulbury Constitution, the Governor General continued to be an appointee of the Queen of England. He had authority to appoint the Chief Justice and other judges. The powers of the Governor were significantly diminished to facilitate a more democratic system in Sri Lanka, and thus the new position of Governor General was born.

A multitude of reforms were introduced following the Soulbury Constitution. Some of them did not settle very favourably with the people. Yet we progressed as a country and we learned from our mistakes. There was still a few remnants of British rule as the Governor General was an appointee of the Queen of England.

The 1972 Constitution was the first autochthonous Constitution. A Constitution that rid us entirely of British rule. It set up a Constitutional Court and the Constitution had a separate chapter on fundamental rights. The 1972 Constitution also got rid of the British-based bicameral Parliament and established a unicameral National State Assembly. A Delimitation Commission was appointed to decide on the number of members to be elected, and finally it was determined that 151 members were to be part of the National State Assembly.

The 1972 Constitution continued with the First Past the Post system, but the First Past the Post system was not without flaws. It became evident when in the 1970 General Elections the SLFP won only 48% of the votes, but won 76.7% of the Parliamentary Seats.

Again in the 1977 General Elections, the UNP won only 50.9% of the votes but acquired 83% of the parliamentary seats. There arose an increased need for electoral reform, especially considering the large number of wasted votes or votes that did not count in bringing people to power. Over and above that, there were other complaints, particularly from minorities. Territorial representation meant that it was significantly more challenging for anybody belonging to an ethnic minority to win an election.

There was no space for minority parties except in areas where the minorities were the majority. For example, Tamils were a majority in most regions in the North while the Muslims were the majority in certain regions of the East. In majority dominant areas, the proposals of the minorities would not even be considered.

Therefore, the Proportional Representation system replaced the First Past the Post system in Sri Lanka following the 1978 Constitution introduced by a J.R. Jayawardene administration. The Proportional Representation system appeared to resolve the problems ingrained in the First Past the Post system.

It optimised minority representation by enlarging the electorates to electoral districts and permitting multiple representatives from that district. Therefore, minority representation improved exponentially.

Furthermore, the votes were calculated proportionately and votes were rarely wasted. Elections for provincial councils had the same effect when provincial councils were empowered after the 13th Amendment in 1987. The Proportional Representation system applied when electing representatives to provincial councils and Parliament alike.

The 14th Amendment also introduced a preferential system to the Proportional Representation system. As according to Article 99 (6)(a) of the Constitution, any political party that amassed less than 5% of the votes were disentitled, and the remaining valid votes were considered to compute the number of seats allocated for each party in the electoral district.

Article 99A, which came from the 15th Amendment, made room for 29 members to be nominated by parties on the National List. The number of National List seats for a party depended on the number of votes received by each party nationally.

Of the remaining 196 seats, 36 seats were distributed among the nine provinces of the country. Each province received four members and distributed as bonus seats. The remaining 160 seats were elected at a district level.

However, there were other problems embedded in to the Proportional Representation system.It came with a racial stigma attached to it, and playing the race card became a strong political tool. The possibility of many candidates competing within an electoral district increased competition and consequently intra-party rivalries grew intensely as elections got closer.

Further to this, candidates had to contest in a much larger territory and it resulted in larger campaign budgets. This meant that the rich were significantly better positioned than others to win.

Furthermore, women still struggled to enter Parliament or provincial councils. Despite the likes of Sirimavo Bandaranaike and Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga attaining the highest offices in the country, there were significantly smaller percentages of women in political office.

The problems became increasingly obvious over the years, and there was a strong call for reform. The Dinesh Gunawardena Committee was appointed in 2003 following a motion filed by the Leader of the House at the time. The report was finally published by the end of 2014 calling for a Mixed Member Proportional system. The Mixed Member Proportional system called for a hybrid between the First Past the Post and the Proportional Representation system.

The reason for having the First Past the Post system is some of its strong attributes which resolved the issues of the Proportional Representation system. It guarantees more accountability of a politician to the people that elected him or her to political office, while the Proportional Representation system guarantees a broader representation of ideas. Further to that, the First Past the Post will also require much smaller budgets to campaign and contest.

The Local Authorities Elections (Amendment) Act was enacted in 2012, to address the imminent issues in local government. An important transformation that came with this amendment was that it addressed women representation in politics. However, nomination by political parties was discretionary and not mandatory, and therefore, there was a requirement for a further amendment in order to make the changes work.

When this Government came to power on 8 January 2015, it embarked on a mission to restore democratic principles and to rectify the errors within the electoral system. This included a vision to improve women representation in politics. Therefore, further amendments were introduced in law to ensure a mandatory 25% representation of women in political office in provincial councils and local authorities.

Furthermore, this Government also sought to enforce the reforms proposed by the Dinesh Gunawardena Committee, as was promised by His Excellency Maithripala Sirisena. Now, every Provincial Council will elect 50% of its members from the First Past the Post system and the remaining 50% of its members from the Proportional Representation system.

The prototype for every subsequent Provincial Council and local authority election has now been mandated in law, and the same electoral process is expected to be applied at Parliamentary Elections. Let us hope these proposals work for the betterment of this country. Let it bring forth a greater representation of women and a far cleaner democratic structure in Sri Lanka.

(The writer is a President’s Counsel and the incumbent Minister of Provincial Councils and Local Government in Sri Lanka. He is an Attorney-at-Law and holds a postgraduate degree in law from the University of Aberdeen, UK).