Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday, 31 March 2018 00:37 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

On our social media or even mainstream, it is not uncommon to find somewhat astounding statements and claims, grossly exaggerating happenings in the country and the doings of our countrymen both of the present and past. This penchant for embellishment is also reflected in common social discourse, even among persons who one may consider better informed and could be expected to be more sceptical. Some things being said by these people are so far from the truth that they amount to untruths.

For the storyteller, facts are secondary to the ‘telling’, the drama of the tale overriding the demands of objectivity and accuracy. But they are not telling fairy tales, but talking about real events and persons here. These are things that with time become history, and like any discipline, dependent on the integrity of the records, for its legitimacy.

The reader relies on these narrations to understand the past, to assess the personalities involved, interpret the processes in motion. There is a big difference in saying that123 died of a plague in the Eastern Province and claiming that 500,000 perished from it for instance. The second figure, rounded to a convenient half a million, if true, would have effectively depopulated the sparsely-populated Province.

Sri Lanka has got talent, the small country that produces giants or even the mouse that roared is the obvious message that we come across often in these stories. Over-emphasis only reflects the inner doubts of the narrator, invariably contradicting the claim. There is no need to paint the lily.

Richest man

The other day I read a piece on late Upali Wjewardena, the controversial business tycoon killed in an air crash about 35 years ago. It was not a simple accident, there was a deep conspiracy behind his death suggests the writer, describing Wijewardena as Sri Lanka’s wonder boy destined to become the “richest man in the world”, had not dark forces brought about his tragic end.

When the accident occurred, somewhere over the East Asian seas, Upali Wijewardena was flying on an executive Lear jet, the preferred mode of travel for the ultra-rich then. I am not certain whether the airplane belonged to Wijewardena or whether it was on charter, the kind of detail that professional business writers would explore. It is immaterial for our purpose; with his riches he was able to do either and much more.

Wijewardena hailed from what is commonly referred to as privileged family background in this country. After a short stint at the local office of a British multinational he moved out on his own to the world of business; confectionaries, radios, assembling of cars, newspapers among other things. Not wanting to remain a big fish in a small pond, Wijewardena was one of the earliest local businessmen to venture into other countries, Malaysia, Indonesia and so on.

These were the days of rigid exchange control and such a move was virtually unthinkable to the average entrepreneur. Wijewardena was well-connected, belonging to the same clan as J.R. Jayewardene by birth and by marriage to the then Prime Minister Sirima Bandaranaike.

There is no doubt Upali Wijewardena was a maverick and an intrepid businessman, but could he have ended up as the richest man in the world? At the time of his death he was not the richest man in Malaysia or even Indonesia, maybe not even among the first 10 in those countries. In the context of our reality, calling someone rich is one thing, but even to suggest that he would have ended up the richest man in the world is surely taking enormous liberties with the writer’s license. We are in the realm of a fairyland where there is no distinction between fact and fiction, possibility and fantasy; it is only the telling that matters, the truth can be just papered over.

By such writing, the reader is being given a distorted view of the world of business and relative financial strengths, but a view perhaps in harmony with his own narrow mindset. There is no effort to explore the massive gap between a dollar millionaire and a dollar billionaire. Imbalances caused by valuations made in a weak currency when translated into a hard currency are just ignored. How much of his wealth is net, minus the credit the local banks had so obligingly extended?

The reader is placed on the same chair the child sat reading Grimm’s Fairy tales. To question the story is to deny one the thrill of the tale. Economically, geographically, even racially, Upali’s prospect of becoming the richest man in the world was well-nigh impossible. Even with all the economic advances made in the Developing world since the 1980s, they have none in the top 10 richest in the world today, and this includes China and India.

Strongest Army

According to some writers we also have (had?) the world’s best Army Commander (and the Army?), who by a trick of fate was pitted against the most ferocious terrorist group in the world (LTTE).Things happening in the small country, good or bad, are repeatedly compared to the world and declared winner.

In military matters, having a distorted assessment of one’s strengths is dangerous, even fatal. It is an area of human activity where you need the coolest and the most objective minds. On the other hand, overestimating the prowess of the enemy, is not as potentially harmful as overestimating one’s strength but lends to overreaction and waste, perhaps also indicating a fearful attitude and a dramatic mindset.

It was only natural that the ending (in 2009) of the long-drawn-out war against terrorism (took more than 30 years) was joyfully celebrated by a long suffering nation. During these three decades neither combatant gained a decisive victory nor did the various governments that confronted the LTTE offer a solution to the problem. Eventually the LTTE, although outnumbered and outgunned by the government forces, overestimated its strength and decided to fight conventionally, defending the territory it held. The result was their total destruction.

It was only natural that the ending (in 2009) of the long-drawn-out war against terrorism (took more than 30 years) was joyfully celebrated by a long suffering nation. During these three decades neither combatant gained a decisive victory nor did the various governments that confronted the LTTE offer a solution to the problem. Eventually the LTTE, although outnumbered and outgunned by the government forces, overestimated its strength and decided to fight conventionally, defending the territory it held. The result was their total destruction.

The conduct of wars, their scope and intensity, are a reflection of the fighting abilities and resources of the conflicting nations. We have sports meets at school level, national level, SAARC games, Asian games, Olympics and so on, with vastly differing performance levels. For the participant, any event taken separately, whether it is a school sports meet or the Olympics, the challenges, effort and the eventual triumph are individually special. But if we were to compare them, one against the other, we will see a world of a difference between them. Wars are similar; there are wars and wars.

Historically, those living in the Indian Sub-Continent, by inclination and culture are a people generally conquered by outsiders and not conquerors themselves. Periodically, various groups have only entered the Sub-Continent to conquer, settle and eventually assimilate, the last, being the Moghuls, followed by the European imperial powers.

This does not mean that there were no wars in the Indian Sub-Continent. But they were mainly against each other, long drawn internecine conflicts that went on interminably, neither party strong enough to bring it to an end. I am not certain how a terrorist group is assessed for their ferocity, but if we take casualties as the yardstick, the less than 100,000 inflicted in 30 years of fighting the LTTE (both sides, including the injured)will make our war a low-intensity conflict.

In the two World Wars fought in early 20th century, we observed battles where millions died in a matter of months or even weeks. Horrendous casualties suffered in recent civil wars in countries like Afghanistan, Syria and Iraq make our war look like a small skirmish.

But the dramatic mindset is unfulfilled. Even today, nearly 10 years after the end of the fighting in 2009, various politicians and military bigwigs impose themselves on a helpless public with huge security details, defensively prepared for a massive attack any moment. There has not been a single terrorist attack since 2009!

Best brains

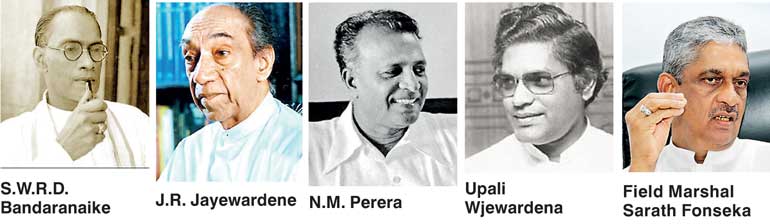

This adulatory approach is not limited to these categories. For every era, we have our giants. There was S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, who was referred to as the silver-tongued orator of Asia, J.R. Jayewardene, the 20th Century Fox in reference to his acclaimed cunning, N.M. Perera with the golden brain was going to lead us to a socialist state, Sirima Bandaranaike, leader of two-thirds of humanity – many so-called specialists whose unique skills can be described only in the superlative in comparison to the world or even the century they lived in, not to forget a whole lot of other outstanding benefactors clamouring to serve the people.

Yet, the country is much troubled and remains one of the poorest in Asia. In the Corruption Index our position worsens, in the Ease of Doing Business (including Government run services) the situation deteriorates daily. You need more than Rs. 150 to buy one dollar today. Every institution in the country has been sullied and diminished.

Does a laudatory reference by a third party, unsubstantiated and loosely made, change an obvious truth? If a country claims so many exceptional personalities, especially in public life, could it be in this pitiable state? As so plainly stated in the Bible, there can be no freedom where the truth is not known. Maybe we can put the question another way; does freedom have any meaning to a people so indifferent about the truth, unable even to grasp the difference between substance and puff?

A friend of mine uses a certain three-wheeler regularly and in the course of time has come to know the driver well. The man has no sense of fairness on the road and will overtake from the wrong side, take drastic U-turns, squeeze his way forward through the slow-moving traffic (jumping the queue, a national trait) and horn incessantly(noise is good, another national indulgence!).

My friend finds him useful when he has to get to a place in a hurry. Otherwise, safety concerns compel him to limit the use of the three-wheeler for short errands only. I have met the driver; thirtyish, though sporting an incipient paunch, thin in a wiry way; ingratiating smile, smallish immature face, a man living on his wits. He is also superstitious and given to rituals, about which he talks excitedly and with assurance. Around his wrist and neck are several talismans and lucky charms, for protection, as he explains. On certain days bathing is to be avoided.

His usual hangout is near a big hotel in Colombo where tourists looking for city tours can be found. This way the man has picked up some English, which is liberally interspersed in his conversation.

One day my friend said to him patronisingly, “I say, you speak very good English”

The man wanted to explain what he took to be the truth; perhaps he has a natural skill for languages.

“I took a ‘Sudu Mahathmaya’ around the city the other day. He said I speak better English than even him!”

A white tourist, enervated by the press of Colombo’s heat and noise, humours the earnest three-wheel driver, little realising that a whole universe could be built on those words.