Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Wednesday, 17 July 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

About three years ago when passing through Punanai along the arterial road between Habarana and Batticaloa, I noticed a few brick structures appearing in a parched land amid thick shrubs and woody trees. It was almost a  desolate spot where I could not see any people living close by. On inquiring from friends, I understood that it was a Saudi-funded huge madrasa built by one Muslim parliamentarian and minister from the Batticaloa District.

desolate spot where I could not see any people living close by. On inquiring from friends, I understood that it was a Saudi-funded huge madrasa built by one Muslim parliamentarian and minister from the Batticaloa District.

My immediate reaction was to question firstly, the need for such a madrasa and that too in a remote place like Punanai where there is no Muslim catchment population, and secondly, the implications of Saudi funding for a madrasa in Sri Lanka especially at a time when Wahhabism, the Saudi Arabian ultraconservative ideology, was falling under the spotlight of international critics who were trying to link that ideology with Islamist extremism. I warned my friends that the project would face immense difficulties on completion at least from nationalist Buddhists. That is exactly what is happening now.

Later on, when reading through an opinion piece by Helum Bandara in Daily Mirror (18 January 2018), it dawned that it was going to be a ‘fully fledged state-of-the art university approved by the University Grants Commission (UGC)’. Well, if Sri Lanka could have private hospitals and private schools why not private universities? However, after witnessing the controversy over SAITM, critical questions once again arose particularly in relation to the difference that this university was going to make to the 15 existing ones managed by UGC, the control over its management, and how profitable was it going to be to avoid becoming a white elephant.

From information collected from print media and television interviews it appears that this university is going to be one controlled by members of the founder’s family, funded almost totally by Arab sources, while offering some advanced scientific and technical courses within an Islamic ambience.

The financial viability of this institution would obviously depend on fees charged from students, size of enrolment and cost of quality academic staff and administration. The figure Rs. 150,000 per semester per student as mentioned in the article referred to would obviously shut out majority of local students but would attract plenty of foreigners. However, that attraction would depend on the quality of teaching staff and standard and novelty of courses offered, both of which should be internationally competitive.

On the contrary, if foreign demand falls and if fees were to reduce to cater to local demand, quality of education offered would have to be compromised, which ultimately would jeopardise the financial viability of the project. One is not sure whether any marketing projections were carried out before venturing blindly into the area of higher studies. Running a private school is different from running a quality private university.

Sources of funding

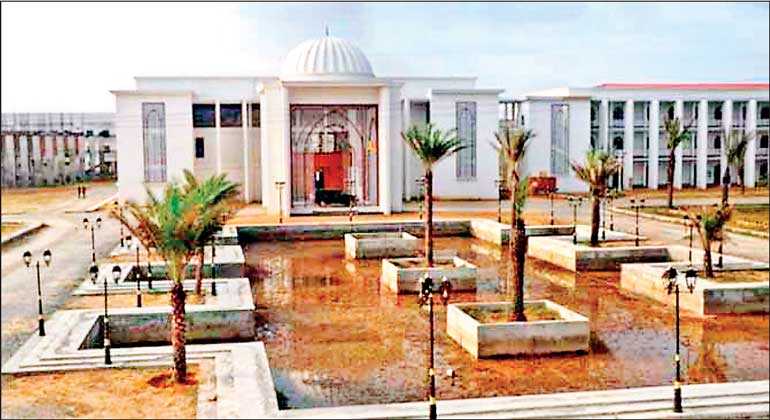

The other issue is about the sources of funding. Whether through interest-free loans or outright donations, all funds would certainly have some strings attached to them. What do these lenders and donors expect in return? This is where suspicion arises regarding the ultimate objective of this university. Even if all funds are channelled legally and through proper agencies in the country, the fact that the lion share of it is coming from Saudi Arabia leaves room for suspecting that the university would ultimately function as an intellectual centre for spreading Wahhabi ideology. To make the situation worse, the architecture of buildings and the appearance of the front yard planted with date palms add an Arab flavour.

This project is another instance where a Muslim leader has been blinded by his political clout and personal avarice to ignore ground realities. A university funded by Arab money with at least one faculty or department to teach Islamic sharia and cultural studies, which would be staffed by Arab scholars at least partially, would certainly be viewed by others as a conduit for religious propaganda. The founder obviously has bitten more than what he could chew. Not much consultancy with academics and Muslim intellectuals seems to have gone into the academic planning of this university.

Historically, Muslim leaders in this country had built and successfully managed educational institutions without provoking envy and suspicion from others. One could pick two instances where Muslim leaders in the past had built institutions of quality and prestige without inviting criticism from other communities. One was the establishment of Colombo Zahira College and the other was Naleemiya Institute.

The first was started at a time when there was a cultural awakening in the country where every community was trying to open educational institutions within its own religious and cultural ethos. Thus, when Muslims understood the national context and embarked on the Zahira project they received not the anger but blessing from other community leaders. Zahira went on to produce hundreds of Sinhalese, Tamil and Muslim scholars, many of whom were of poor economic background but went on to serve the country with patriotism and dedication while remembering with pride their debt to Zahira.

The second, Naleemiya Institute, although of a different genre and catering entirely to the needs of Muslims, was the brainchild of one patriotic local Muslim philanthropist, popularly known as Naleem Hajiar, whose generosity extended even to the government of the country, at a time when the nation as a whole was in dire straits to finance its imports.

There was no foreign donation or loan involved in that project, and there was no grumbling from any community when it was opened. Instead, the advice of Naleemiya’s founder was eagerly sought by the then socialist finance minister Dr. N.M. Perera, who ultimately became an admirer of the entrepreneurial spirit and patriotism of that founder. Naleem Hajiar, a businessman when entered the field of education knew his limitations, but was never reluctant to entertain with enthusiasm advice from prominent educationists of that time like A.M.A. Azeez and Bdiuddin Mahmud.

These were two instances where Muslim leaders worked within the national ethos while serving their own community. More importantly, both Zahira and Naleemiya, unlike the aborted Punanai University, were not institutions intended to make private profit. In a sense, those two icons bear silent testimony to the quality of leadership which Muslims were able to produce in the past.

The question now is what should be done with this aborted project? Its founder argues that the university cannot be taken over by the Government legally. With reasonable compensation the Government should be able to acquire it and utilise the facilities and preferably for educational purposes.

Why not turn it into an international institute of research and postgraduate studies in agricultural and veterinary sciences? The land is part of the Mahaveli Development Scheme and the area is suitable for agriculture and cattle farming. Hence, a research centre in that field will be apt. It can be an entirely independent institution or part of another existing university.

Having said that, there is still a need for an ‘Islamic’ university of a different type. Why not this aborted project be converted to such an institution in Sri Lanka? There had been a spurt of Islamic universities operating in various parts of the Muslim world. These universities are products of a petro-dollar era. Even though they are called Islamic there is hardly any difference between them and other non-Islamic universities particularly in respect of curricula taught and courses offered, except may be in the coverage of Arabic and Islamic studies.

Even in those studies they are unable break the hold of Islamic orthodoxy. Yet, not one of them so far had been able to attain a place within the top 100 universities in the world. Why therefore an ‘Islamic’ university and that too in Sri Lanka?

I want to refer to the thoughts of a Muslim internationalist, activist, thinker and intellectual, Eqbal Ahmad (1933/4-1999), whose proposed Khaldun University, named after Abdul-Rahman Ibn Khaldun, a 14th century historian and sociologist, and a secular and scientific figure, received international support from Muslim intellectuals who even wanted to work for this secular institution pro bono. After showing some initial enthusiasm and support by the Government of Pakistan under Benazir Bhuto, she and the forces of business and religious conservatism jointly sabotaged that project. I concur with his view that, “the Muslim people, or for that matter any people in the world, will not make a passage from a pre-industrial traditional culture and economy to a modern culture and economy without finding a linkage within finding forms and relationships that are congruent between modernity and inherited traditions … My argument is that we will not be able to fight fundamentalism until we produce a modern progressive secular educated class of people who know the traditions and take the best of it” (Eqbal Ahmad, Confronting Empire, Interviews with David Barsamian, Cambridge, Massachusetts: South End Press, 2000, p.22. Emphasis added).

A modern Muslim university to realise this vision of Eqbal somewhere in the world is an absolute need of our time. It will be a sound first step to reform even the madrasas eventually. However, given the prevailing climate of ultra-conservative Wahhabi hold on educational institutions, the very forces that sabotaged Khaldun University in Pakistan would do the same in any Muslim country. That is why had the politician and minister of the aborted Punanai project taken the bold step to establish from the outset a secular university based on Islamic rational tradition, he would have at least garnered support from intellectuals around the world to counter the criticisms that he is facing now.

Sri Lanka could have pioneered this venture and contributed immensely to restart a tradition lost by Muslims centuries ago. Such a university would have won a unique status and earned an unparalleled prestige to this country in the Muslim world. Unfortunately, the entire Muslim political leadership in Sri Lanka lacks that progressive vision. The aborted university project was a golden opportunity squandered by abuse of political power, subservience to Wahhabism and hunger for profit.

(The writer is attached to the School of Business and Governance, Murdoch University, Western Australia.)