Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Wednesday, 15 November 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

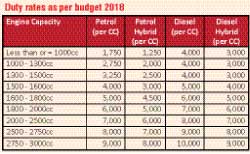

The key change in the Budget of 2018 is that motor vehicle duty is no longer calculated on values, but on the cubic capacity (CC) of the engine, be it petrol, diesel or hybrid, and the Kilo Watt (KW) output of the electric motor for an electric vehicle (EV)

Background

Historically, Customs duty on motor vehicle imports has been calculated on the CIF value of the vehicle. In Customs terminology, the value for Customs duty is assessed on the price “paid or payable” by the importer.

The assessment of value for duty computation has a significant impact on the selling price of a vehicle, because duty in Sri Lanka is so high. Duty for a 2,000 CC1 petrol vehicle used to be an effective rate of 184% of the price paid or payable. Thus, if the value for duty purposes were to drop by one rupee, the cost of the car would drop by Rs. 1.84.

The assessment of the value for customs duty purposes has always been a challenge, and in my assessment, the complexity of making this assessment has historically lead to a loss of revenue to the Government.

The key change in the Budget of 2018 is that motor vehicle duty is no longer calculated on values, but on the cubic capacity (CC) of the engine, be it petrol, diesel or hybrid, and the Kilo Watt (KW) output of the electric motor for an electric vehicle (EV).

I feel this system is much more equitable to all segments of the industry, including the customer. From the Government point of view, the system is transparent and easy to administer.

What did the Government set out to achieve from the Budget?

Reading the Budget speech, and studying the relevant appendices, it seems the Government set out to achieve the following:

If these were the objectives of the Government, I feel the Budget has been very successful. Infact, I feel it has been one of the most successful budgets for the automotive industry in recent times.

Create transparency and a level playing field for various segments of the industry

The table defines the import duty on any vehicle to be imported into Sri Lanka. All you need to know to work out the import duty of a vehicle to be imported is the CC of the engine, and whether it is petrol, diesel, petrol hybrid, diesel hybrid, or electric. Once you define which of the four sources of power the vehicle to be imported is powered by, and you define the power of the vehicle, the table allows you to simply and easily calculate the duty payable. This is the easiest system of duty calculation that has ever been implemented in Sri Lanka.

This system is transparent to everyone. The system is absolutely easy to implement. It is not open for interpretation and thus not open for abuse.

Maximise revenue and minimise leakages

The transparency of this system will stop the leakages that were prevalent to this point. These leakages existed because some importers could benefit from the complexity of motor vehicle valuation and get away with lower duty payments. Thus, the Government will be able to collect greater revenue through the recommended system. Infact, the estimated revenue collection from import duty is Rs. 25 billion. I feel this target could be exceeded.

Limit outflow of foreign exchange

If you look at the steep cascading of the duty rates applied to vehicles with more powerful engines, it shows a steep cascading of duty applicable for more powerful engines, and even within a CC band, the smaller engine pays significantly less import duty than a more powerful engine.

Take for example a 1,000 CC petrol car compared to an 800 CC petrol car, the more powerful 1,000 CC car would attract a customs duty of Rs. 1,750,000 (Rs. 1,750 x 1,000) compared to the 800 CC car attracting a duty of Rs. 1,400,000. Rs. 350,000 is a very material sum of money in this market segment. Most people buying the smaller  cars buy them on lease. An average four year lease repayment would cost Rs. 1,500 per Rs. 100,000 borrowed. This, the 800 CC car would cost Rs. 5,250 per month less on a lease. This again, is a material sum of money in this market segment and hence the policy will be effective to drive consumers to purchase less powerful engines.

cars buy them on lease. An average four year lease repayment would cost Rs. 1,500 per Rs. 100,000 borrowed. This, the 800 CC car would cost Rs. 5,250 per month less on a lease. This again, is a material sum of money in this market segment and hence the policy will be effective to drive consumers to purchase less powerful engines.

Whist a 1,000 CC petrol vehicle attracts a duty of Rs. 1,750,000 a 1,300 CC petrol vehicle will attract a duty of Rs. 3,536,000. This further proves the budget will persuade consumers to purchase smaller engine vehicles.

nEncourage fuel efficiency via encouraging the import of hybrids

The table shows that a hybrid vehicle below 1,000 CC petrol attracts a duty of Rs. 1,250 per CC and hence the duty of a petrol hybrid would be Rs. 100,000 less than that of a compatible petrol non-hybrid.

The benefit of pushing consumers towards smaller engines and hybrids will lead to a significant reduction in expenditure of fuel. Hybrid vehicles are atleast 25% more fuel efficient than non-hybrid vehicles. So, if all vehicles in Sri Lanka were to move to hybrid, we could save 25% (or more) on the total import value of fuel for motor vehicles.

The total value of fuel imported for transport is approximately $ 1,700 million2.This is around 9% of total imports and one of the largest imports for the country. Comparatively, the total import value of “transport equipment” which is not just motor vehicles but all transport related equipment including agricultural equipment, earth moving equipment and may even be rolling stock3 is $ 931 million. This means that the foreign exchange outflow from the import of vehicles is much less significant than the foreign exchange outflow from the purchase of gasoline.

Assuming the entire fleet of Sri Lanka’s motor vehicles were to move to hybrid, which could bring a 25% saving in fuel imports, this saving would translate to $ 439 million. This value would be 4% of our total exports. The point being made is that any possible saving in fuel is significant in the context of import reduction and balance of payments.

In context of reducing fuel imports, the benefits given for the import of electric vehicles is very significant.

The arguments presented above show that the Budget 2018 has actively targeted the balance of payments improvement in a two-pronged manner. On one side, it is actively discouraging the import of expensive motor vehicles through an import duty that cascades steeply for more expensive vehicles (through the increase of import duty in relation to CC) and on the other side, though the encouragement to import more efficient transport equipment and thus reducing the import of fuel.

The benefit of EVs are not merely derived from the benefit of reduced fuel imports. The main benefit of an EV is that the vehicle, in terms of its design, is fundamentally more efficient than an Internal Combustion Engined (ICE) vehicle. In terms of energy efficiency, an ICE vehicle is estimated to transfer only around 50% of the input energy to the vehicles driven wheel. An EV is estimated to be able to transfer over 90% of the input energy to the driven wheel. This is a significant difference in efficiency.

The argument that Sri Lanka’s national grid is powered by fossil fuel and hence EVs don’t bring efficiency is thus negated. Further, the potential to capture more solar and other alternative energies in Sri Lanka support the strategy that we should actively promote EV adoption.

Professor Ashok Jhunjhunwala, of the Department of Electrical Engineering, IIT Madras, and automotive advisor to the Indian Prime Minister, addressing the Automotive Component Manufacturers Association (ACMA), at their annual sessions 2017 in New Delhi stated that research showed that if all the vehicles in the world were to immediately convert to EV’s, the world would only need to increase its electricity generation by 10% and this increase could easily be generated by sources of alternate energy without resorting to using more fossil fuel.

the Indian Prime Minister, addressing the Automotive Component Manufacturers Association (ACMA), at their annual sessions 2017 in New Delhi stated that research showed that if all the vehicles in the world were to immediately convert to EV’s, the world would only need to increase its electricity generation by 10% and this increase could easily be generated by sources of alternate energy without resorting to using more fossil fuel.

Many countries have announced that all vehicle registrations will be electric by around 2025 onwards. Sri Lanka has made the announcement in this budget, with an announced date of 2040. This target I feel is conservative, but at least we have a target.

Reduced EV duty for brand new vehicles

It is noteworthy that the Budget has an increased rate of duty for used vehicles, and a cheaper rate for new vehicles. This makes a lot of sense, as the lithium ion battery in EVs have a life of around five years. At the end of its life, the battery needs to be responsibly recycled. Sri Lanka is presently developing the battery recycling infrastructure and hence, the Government granting an added benefit for new vehicles is a sound strategy.

Some importers argue that the agent for Nissan doesn’t import the Nissan Leaf as a brand new vehicle and in order for this vehicle to be imported, this criteria should be deleted. The issue is if this criteria is deleted, it allows for older vehicles to be imported, and this is not in the best interest of the country.

Set direction for the industry

The Budget 2018 is encouraging the import of smaller engines, encouraging the import of hybrids which are more efficient and encouraging the adoption of EVs. One hopes that the Government will keep reinforcing these objectives so that the industry will take the cue from the government and present the consumer with transport solutions that are cleaner and greener. The Government’s sustained assertion of these objectives will also spur the provision of the infrastructure required to promote and facilitate accelerated EV adoption.

Safety congestion and underemployment

The Budget has, for the first time, introduced minimum safety standards for motor vehicle imports. The Budget requires all vehicles being imported into Sri Lanka to have airbags, anti-locking brakes (ABS) and three-point seat belts.

With the introduction of highways and better quality roadsthat increase the driving speeds in the country, these import restrictions must be welcomed. I feel the adoption of these minimum safety standards are well timed and one hopes that the Government will not alter these restrictions during the Budget debates.

The Budget imposes import surcharges of trishaws and concurrently gives significant encouragement for the import of electric trishaws. I personally feel that the trishaw has provided yeoman service to the people of Sri Lanka by supporting public transport when the Government could not afford to upgrade it. However, I feel the product has reached the end of its product lifecycle. The road conditions and the traveling speeds make the trishaw unsafe, particularly when they travel on inter-city A roads.

We have also been reading about the shortage of labour in Sri Lanka. We have 1.1 million trishaws, which also means the same number of our workforce are driving trishaws. If we are in need of a trishaw, in most cities in Sri Lanka, we don’t need to wait more than two to three minutes to hail one. Have we reached the point of saturation of trishaws and do they bring about underemployment4?

Permits

Permitshave become an integral part of the Sri Lankan motor industry. Permits allow Government employees to purchase a vehicle at a reduced duty. Given our high duty environment that has been in effect for the over the past decade, ‘permits’ presents a significant benefit to the recipient. Most Government employees do not avail themselves of this benefit and instead pass on their benefit to a third party.

In the broader usage, the concept of the permitcould be interpreted as the Sri Lankan publicmaking a transfer payment to Sri Lankan Government employees. In return, the public are able to purchase a vehicle at a reduced duty. This transfer payment does make sense as it enhances the remuneration of the Government employee, without increasing the Government wage bill and thus Government recurrent expenditure.

Permits have historically caused distortion within the industry. The reason for the distortion is that in effect, one US dollar can change the effective rate of duty from 100% to 200% or even more. The permits had limits to the CIF value of vehicle that can be imported under its cover. This distorted the industry in terms of giving significantly increased sales volumes to vendors whose products came under the purview of the permit, and adversely disadvantaging those whose products didn’t come under this purview.

The present Budget does away with the CIF limit on the permit and gives a specific rupee discount on duty payable. The fact that permits are recommended to be transferable takes away the previous circumvention of this somewhat dubiously.

Which cars are cheaper and which are more expensive?

The Budget has not made vehicles that much cheaper. Infact, many vehicles are more expensive than they were. But, the difference in many cases is not hugely material.

The 2,000 CC syndrome – regressive taxation

The best example to explain the problem of regressive taxation, is as an example a Mahendra Scorpia. It is a robust and utilitarian 4x4, with a 2,523 CC diesel engine. The CIF price of this vehicle should be around $ 17,000. That isaround Rs. 2,635,0005. The duty, based on the present system is Rs. 22,707,000. This is an effective rate of duty of 861%. This probably beats all world records of the highest incidence of duty. So, obviously the Scorpio won’t be attractive in Sri Lanka.

Does this example serve to discredit this method of levying Customs duty?

Looking at this question from the point of view of the Mahendra Scorpio, on one hand, the prevalent duty mechanism renders the product unsellable. However, if we were in the regime of CIF based duty, and a competitor selling a similar product imported in at a cost for duty purposes of $15,000the Scorpio would again have been uncompetitive. This sort of issue was prevalent during the previous form of valuation.

Another point to note is that many European manufacturers have luxury vehicles like Mercedes S Classes, BMW 7 Series, and the Range Rover with sub 2,000 CC petrol and petrol hybrid engines. These vehicles will now be cheaper than they were because of the CC based duty. On the other hand, the duty on some of the larger engine vehicles could be higher than before.

The point I am making is that the methodology adopted by this budget is not infallible. Like any proposal, it will see some winners and some losers. But, in an overall sense, based on my experience in the automotive industry in Sri Lanka, I feel the method of calculating duty as per the suggestion of the 2018 Budget will be the more equitable to all industry stakeholders, than any other methodology implemented.

The regressive nature of the duty incidence, as explained with an extreme example in the above paragraphs, could occur in the category of petrol vehicles upto 2,000 CC and petrol hybrid vehicles upto 2,000 CC. Today, most manufacturers’ flagship models are available in a 2,000 CC engine format.

Take for examplethe BMW 7 series, available in 2,000 CC petrol. So is the BMW 5 series and so is the BMW 3 series, and also the BMW X3, and X5. All the listed models will attract the same Customs duty. Rs. 12,000,000. Since the CIF prices of the listed vehicles are very different, the dutyas a percentage of CIF will vary. Some may argue that this is unfair and regressive.

If one were to look at this issue from the purview of the Government, a 2,000 CC engine consumes similar amounts of oxygen and emits similar amounts of carbon monoxide into our environment. The listed cars take very similar amounts of space on our roads. They consume nearly identical amounts of fuel. So, then, why shouldn’t the Government levy a uniform tax on any 2,000 CC engine?

The problem in Sri Lanka is that we are used to a cheaper model differing from a more expensive model by a large rupee differential, because we are used to the price difference being a function of price multiplied by duty. If we were buying a car in the US, where duty is near non-existent, then, the difference in price of the vehicles in the above example would be merely a function of the difference in the manufactures’ price of the listed models and the sellers’ margin. The price difference would be small. With the CC based duty system, the price differences for different models with the same CC engine will be smaller that we are accustomed to. I don’t think it is fair to attribute this change as a demerit of the CC-based duty system.

Summary

I reiterate that I feel the proposed system of levying duty on motor vehicles is more transparent, easier to administer and broadly more equitable for the industry. The transparency and the added competition that this methodology will bring will ensure the consumer gets the best possible deal. The system will ensure that the Government collects stable revenue with no possibility of leakage.

(Sheran Fernandois the Managing Director of Innosolve Lanka Ltd., a company focused on promoting the adoption of electro mobility in Sri Lanka.Innosolve is a partnership between MMBL-Pathfinder, the Peninsular Group Australia, the Tissa Jinasena Foundation and Sheran and Roshni Fernando – automotive industry specialists, with experience in growing brands such as Land Rover, Jaguar, Suzuki and Citroen.)

Footnotes

1Cubic Centimeter

2An approximation based on data from CBSL Annual Report 2016 and Petroleum Corporation published data.

3The definition of the term transport goods is not clear

4is the under-use of a worker due to a job that does not use the workers skills, or is part time, or leaves the worker idle.[2] Examples include holding a part-time job despite desiring full-time work, and overqualification, where the employee has education, experience, or skills beyond the requirements of the job.[3][4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Underemployment

5at Rs. 155 to the US$