Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Thursday, 2 April 2020 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

This space is named the ‘Lanka Guardian column’. The title Lanka Guardian is from the two-decades-defunct magazine of which my father was Founder-Editor. I was Assistant Editor, Associate Editor and  (for two years) Editor of that once-celebrated fortnightly journal.

(for two years) Editor of that once-celebrated fortnightly journal.

I realised that the conjuncture in which I was commencing this new column in February 2020 upon (collective) recall from Moscow where I served as Ambassador, is rather reminiscent of that in which Mervyn de Silva chose to launch the Lanka Guardian on 1 May 1978, and especially evocative of what Kumari Jayawardena judged “the best…the first ten years of the LG” (as it was dubbed by readers).

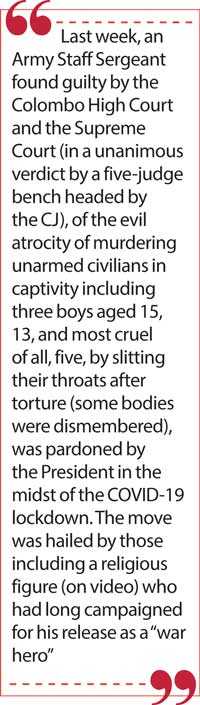

Last week, an Army Staff Sergeant found guilty by the Colombo High Court and the Supreme Court (in a unanimous verdict by a five-judge bench headed by the CJ), of the evil atrocity of murdering unarmed civilians in captivity including three boys aged 15, 13, and most cruel of all, five, by slitting their throats after torture (some bodies were dismembered), was pardoned by the President in the midst of the COVID-19 lockdown. The move was hailed by those including a religious figure (on video) who had long campaigned for his release as a “war hero”.

In a colourful set of slides dated 30 March 2020, Gevindu Cumaratunga, longstanding Alt-Right ideologue, Chairman of the Yuthukama national organisation, Editor, ‘Yuthukama’, and SLPP National List nominee whose allegedly vanguard, catalytic ideological contribution to the MR Movement’s speedy revival in 2015 was publicly felicitated by the SLPP chairperson recently, poses the questions:

“Mass murderers? Barbaric child killers? Mass murder by the courts?” and follows up with “Barbaric child slayers? When little children are used for war, intelligence gathering and covering up intelligence gathering and are slain as a result, who are the real child-slayers?... Mass murder by the courts? Who can say that the court verdicts of the past five years were not political ones? Who can say that these verdicts saying our Army committed war crimes were not delivered in accordance with the Geneva betrayal? Were the honourable courts a weapon of mass murderers?... Who can say that the previous wicked government did not tempt the honourable judges into becoming mass murderers?” (www.yuthukama.com, 30 March 2020)

Contrary to such conspiracy theory, the process of Military Police inquiry and arrest (2000), prosecution by the AG’s Dept. and Court proceedings (Anuradhapura Magistrate’s Court 2002, Colombo High Court trial-at-bar 2003) commenced well over a decade, and two Presidencies, before Yahapalanaya and the Geneva 2015 Resolution.

In a courageous act, 22 civil society organisations condemned the Executive pardon. The pardon was not only morally abhorrent, it was counterproductive. The repeatedly confirmed judicial verdict furnished GoSL the argument that such atrocities were an exception, not the norm for the Army—indeed the initial arrest/inquiry in 2000 was by the Military Police on a Brigadier’s instructions.

By overriding the verdict of the Supreme Court in the case concerning so ghastly a war crime, the release succeeded in perforating the dense corona shroud to make the international media, prompting the New York Times to report, The Hindu to editorialise, and reputed global institutions on Human Rights to protest, that expectations of justice through domestic Sri Lankan processes have been conclusively, irrefutably, shattered. Ironically, the Presidential override seemed to vindicate Zaid al Hussein’s damaging assertion that in the matter of possible war crimes and crimes against humanity, purely domestic judicial processes in Sri Lanka were foredoomed.

The whole issue triggered in my memory the brutal extrajudicial execution of the (unarmed) brothers Inbam and Selvam Vishvajothiratnam in the late 1970s/early 1980s, and the courageous protest by the Movement for Inter-Racial Justice and Equality (MIRJE) —of which I was a founder signatory/member—an organisation born the same year as the Lanka Guardian, which unfailingly carried MIRJE statements and serialised its reports. Another ethical horror around the same time was President Jayewardene’s pardon of child rapist Gonawela Sunil.

Coming back to the present, what could possibly exonerate or extenuate the quite deliberate cutting of the throat of a five-year-old child? If there is to remain even the most fundamental foundation of ethics and morality, the most basic sense of right and wrong, good and evil, in State, society and leadership, should the Supreme Court’s unanimous verdict have been overthrown?

Is the 2013-2015 ethos perceived as the juridical gold standard, with subsequent judgments somehow deficient in legitimacy?

Prequel

I saw the scorecard of winners of the 2019 Annual Journalism Awards in a Lankan Sunday newspaper while I was in Moscow, and there it was, top of the chart, the Mervyn de Silva award for the Journalist of the Year, named after my late father, won this time by a Veerakesari staffer.

Having been the Editor-in-Chief of the two major newspaper groups in the country during his lifetime, Mervyn was dismissed by successive, ideologically contrasting governments. Regi Siriwardena summed it up: “Before the decade was out, Mervyn had twice been deprived of his editorial chair, once by the management of Lake House, now State-owned, and once by the privately-owned newspaper enterprise he joined thereafter. Both found him too independent, too little content to be the docile slave.” (Foreword, ‘In His Time: Selected Tributes to Mervyn de Silva 1929-1999’, ICES Colombo.)

Mervyn founded the Lanka Guardian magazine which he edited until his death, except for a two- year interregnum, 1996-1998, during which I edited it at his insistent request. When he died 20 years ago, I suppose I could have tried to restart the magazine, but I was always a Prodigal Son and had other ‘projects’ of ‘intervention’—adventures, experiments, endeavours—to embark upon. Now a cycle is over, a new one begins.

The LG was born one year after the UNP swept away the SLFP—reducing it to not even the largest Opposition party—decimated the Left evicting it from Parliament, and won not merely a two-thirds but a five-sixths of the Parliamentary seats. The LG emerged in a new historical conjuncture, when the UNP government had promulgated a new Constitution and changed the model of the State to one of an overcentralised executive Presidency, devoid of the separation of powers and checks-and-balances that characterise the US Constitution and its Presidential system.

A strong leadership striving to catch up for lost time in swiftly developing the country along Far East/East Asian Cold War authoritarian lines, a Cabinet comprised of the “best and the brightest” of the Sri Lankan political Establishment and containing a strong Sinhala ultranationalist component led by Industries Minister Cyril Mathew were the characteristic features and collective self-image of a new, determined dispensation. The milieu was one of expansive elite confidence, disciplinarian authoritarianism, coercive political intolerance, a Sinhala nationalist streak, and a tough-minded, hard-charging regime poised for economic takeoff. Takeoff there was indeed, with the first year of the new government clocking an 8% growth rate.

For its part, the LG editorially emphasised that there was a looming crisis, the crux of which was the unresolved ethnic or nation-building question, exacerbated by an authoritarian ethos and “the concentration and centralisation of power” in a top-down model.

The founder-editor repeatedly cautioned that the ethnic issue was no longer a purely internal one and the inextricable interface of the ethnic and external dimensions would cause a crisis in the island’s relations with the world, including and most importantly with the neighbour. The LG’s prognosis proved dramatically correct.

National Security State

As early as 26-27 May 1984, the United Nations University (UNU) South Asian Perspectives Project in association with the Lanka Guardian, held a symposium, which included a cluster of workshops, on “Ethnic Relations and Nation Building in Sri Lanka”, attended by 25 religious leaders, scholars, journalists and trade unionists. Professors Shelton Kodikara, Karthigesu Sivathamby and Dr. Newton Gunasinghe (who coordinated the symposium) were among them. I was one of those 25 participant-signatories.

The Final Report of the seminar recommended that “political structures” be “reformed” so as to make for autonomous Regional councils. Federalism was never on the table. Part IV of the four-part report was on ‘The International Context’ and drafted primarily by co-chair of the seminar, Lanka Guardian Editor Mervyn de Silva. The full report, carried in the LG, was republished in the UNU volume ‘The Challenge in South Asia: Development, Democracy and Regional Cooperation’ edited by Ponna Wignaraja and Akmal Hussain (United Nations University Press/SAGE publications, 1989).

Mervyn’s Report on the ‘International Context’ cautioned that: “In the event of a total failure to achieve a negotiated political settlement…the cumulative effects of these already discernible processes will see the Sri Lankan state acquire some of the structural characteristics of the State of National Security, a familiar Latin American phenomenon”.

This was the development and conclusion of Mervyn de Silva’s oft-repeated observation in his columns that in Ceylon/Sri Lanka, a State of Emergency, which by definition was a regrettable exception, had become the norm. Today in 2020, when a Presidential-military bureaucratic framework, inevitable and imperative for intervention in the country’s current situation during a horrific global pandemic, is ideologically touted as a model of State and governance superior to the civilian democratic political model, Mervyn’s astute observation assumes a grim contemporary relevance.

The LG and its Editor were far more critical of the hawks, Sinhala hardliner Industries Minister Mathew and National Security Minister Lalith Athulathmudali—the intellectual antithesis of what the LG stood for—than of President Jayewardene. Mervyn debated the National Security Minister in several forums and mounted a sustained critique of his policy paradigm, including in lectures and conference papers. An Oxford-educated lawyer whom fellow Oxfordian contemporary Chris Hitchens reprovingly quoted as saying in his new Ministerial capacity that “we have to smash heads”, Athulathmudali had taught at Tel Aviv University and was a friend of US Secretary of Defence Casper (‘Cap’) Weinberger. The powerful, articulate National Security Minister’s doctrine was that Israel was both a desirable model for Sri Lanka as well as an omnipotent partner/ally who could intercept and deflect all external pressures.

The Lanka Guardian was a trenchant critic of the foreign policy deviation from Non-Alignment of the new Sri Lankan government. Deriving from a sophisticated awareness and sure sense of world affairs, the journal’s Founder-Editor was scathing about the ignorance of “geopolitical realities” and the delusional folly of the blinkered National Security ideology when applied to complex, “kaleidoscopic” ethnic, external and ‘intermestic’ (Kissinger’s coinage for the interface of ‘international’/‘domestic’) problems. Mervyn defined these “geopolitical realities” as “who we are, what we are, where we are”. The ‘seismic shock’ (Mervyn’s words) of Sri Lanka’s international isolation during the external intervention of 1987 proved the LG had a greater grasp of geopolitical Realism than did the National Security elite and its ideologues. (‘Crisis Commentaries: Selected Political Writings of Mervyn de Silva,’ ICES, Colombo 2001.)

The LG’s exception

The LG was critical of the accentuated asymmetry and inequity of the economic development model. Interestingly for 20 years its pages hardly contained criticism, if any, of Prime Minister Premadasa and/or his programs, and was far more sympathetic editorially to the populist Premadasa presidency than it had been in its first decade of publication towards the predecessor Jayewardene conservative centre-right dispensation.

That striking exception in a journal of critique was on a continuum with Mervyn de Silva’s sympathy dating back at least to the early 1970s for Premadasa, at the time a maverick populist Opposition MP heading a third tendency in a defeated party which was split three ways. D.B.S. Jeyaraj’s well-researched recent feature provides the evidence:

“…Ranasinghe Premadasa came out with a proposal that the UNP should be restructured as a grassroots party from the village upwards. Dudley dismissed the suggestion rudely and refused to put it to the vote or entertain it further…Premadasa quit the UNP Working Committee but not the parliamentary group or the party. He formed an independent people’s organisation … ‘Puravesi Peramuna’ or ‘Citizens Front.’… Premadasa had raised three issues. One was about the UNP not holding the party convention for many years; the other was about the UNP Working Committee functioning for years without renewal of membership or mandate; the third was on the lack of progress in implementing party reform proposals. Furthermore, excerpts from the letter sent to the UNP Working Committee by Premadasa were published in the Daily News of 31 March and 1 April 1973. The Daily News was then edited by renowned journalist Mervyn de Silva…Dudley was shocked further when a harsh rejoinder from Premadasa was published in the Daily News of 9 April.” (http://www.dailymirror.lk/opinion/Ranasinghe-Premadasas-Citizens-Front-revolt-in-UNP/172-184986)

“…Addressing the Colombo West Rotary Club on 4 April 1973 in a speech titled ‘A plan for Sri Lanka,’ Premadasa boldly outlined his vision for the future of the country; a vision that was not to the liking of many UNP heavyweights then…” (Jeyaraj, Ibid)

When Mervyn was the sole editor to publish Premadasa’s letters in 1973, he was a figure of the Colombo 7 elite and (ostensibly) a pillar of the Establishment, the Editor-in-Chief of Lake House newspapers and a Director of Lake House, promoted while Editor Daily News by the Bandaranaike Government, while Premadasa was a rebellious outsider taking a radical-populist line against the entire Establishment, both Government and UNP, with little-to-no prospect of success.

Thus, in the early 1970s Mervyn sympathised with a Lankan version of the Third World’s nationalist-populist and broadly social democratic outsiders/underdogs who as eventual leaders of their nations were to become the archetype and drivers of the Non-Aligned Movement, neither “neutral” nor members of competing Cold War military blocs.

Another opinion

The situation that prevailed in the mass media at the time of the launching of the Lanka Guardian, and its possible relevance to our present time, is evidenced in this excerpt from the Editorial in the journal’s inaugural edition:

“The proper functioning of a pluralist democracy pre-supposes the free interplay of diverse opinions. The freer and more active, the better. Given the structure of the major media, the dominance of the official and the conventional view is no aberration. What is unnatural and therefore unhealthy, is the conspicuous absence of other opinions and perspectives which by calling into question or openly challenging the all-too easily accepted orthodoxies, stimulate intelligent discussion…If we may dignify this exploratory venture in Sri Lankan journalism and embellish our ordinary wish with the formal ostentation of a motto, it is: OTHER news, and ANOTHER opinion.” (“Other News, Another View”, 1 May 1978, Lanka Guardian)

“... However miniscule, ours is a corrective, the corrective of a countervailing force.” (Mervyn de Silva, Lanka Guardian, ‘The First Year’, 1 May 1979)

This column will contribute by providing “Another Opinion”. It is not only the rulers who are born into a legacy which they consciously assume at some point. Everybody has his or her legacy; their inheritance, of which they must never be prisoners but must, at some stage, recognise, shoulder, carry forward, apply and add to in their own manner, while facing the challenges of their time.