Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Tuesday, 24 December 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

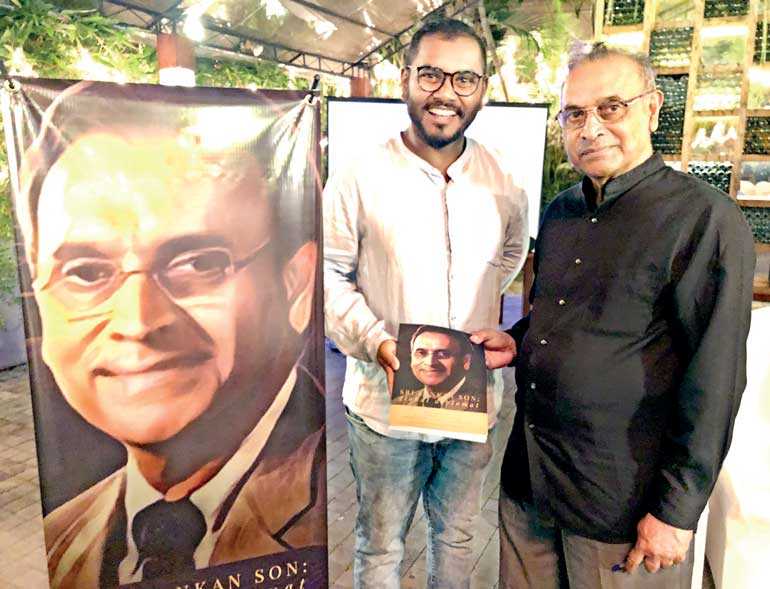

Ambassador Jayantha Dhanapala at the launch of his book ‘Sri Lankan Son and Global Diplomat’

It is an honour and a pleasure to be here on this occasion, marking the launch of the book ‘Sri Lankan Son and Global Diplomat’ about one of our most outstanding public servants and internationally recognised diplomats, Ambassador Jayantha Dhanapala.

The volume is a treatise on a range of international and national matters. It reminded me of just how much we learned from Ambassador Dhanapala, and indeed from his peers, some of whom are present here today, as our generation started our own diplomatic careers over four decades ago.

It has been a complex but rewarding learning curve. Believe me, it was taxing too. He set high bars – frustrating for a few but enriching for the most. Working with Jayantha Dhanapala left something special about him etched in my mind. He is an assiduous builder of common ground – a difficult but indispensable part of effective diplomatic craftsmanship. Our work in Geneva and New York during some of the most testing times for Sri Lankan diplomacy made one thing clear. It is that consensus building is a fine art of engineering decisions that endure, and are seen as win-win solutions for all – not winner takes all solutions.

Paradoxically, a win-win is also based on the pragmatism that consensus-making is not about crafting perfect happiness in a negotiated outcome, but essentially an equitable distribution of some unhappiness among all stakeholders. This applies equally to international diplomacy as Ambassador Dhanapala had ably demonstrated, as well as to pressing national challenges like the ethnic conflict and accountability issues. In this latter case, our political leaders have demonstrably failed to build consensus, thereby making such national responsibilities migrate abroad to become international challenges.

The controversial Human Rights Council Resolution 30/1 which is hotly debated on many national platforms is a case in point. The recent elections in Sri Lanka showed how unwise and impractical such an approach to consensus building was, especially on the sensitive and contentious issue of accountability.

These reality checks bring me to the substance of the volume being launched today. It touches on a range of national and international issues. Although made at different forums at different times during his distinguished career as a national and international civil servant, Jayantha Dhanapala’s articulations resonate with much relevance to some of the ongoing national debates concerning governance, human rights, diplomacy and foreign relations.

But to truly appreciate the message, one must touch upon the messenger.

Jayantha Dhanapala has been a multi-purpose resource for the Sri Lankan public service, particularly for the Sri Lanka Foreign Service. He has been a guru, mentor, counsellor, an intellectual test bed, and above all, a decent and humane friend to many of the Foreign Service folks of my generation. His career has been truly multi-faceted, encompassing both private and public sectors at the national level, and high level role playing in the international arena. He rendered distinguished service as our Ambassador to various nations as well as to the United Nations, admirably safe-guarding Sri Lanka’s national interests at critical junctures of recent Sri Lankan history. As an international civil servant, rising to the level of the Under Secretary General of the United Nations, he made significant contributions in the fields of policy, practice as well as research in the realm of international peace and security.

His retirement has been a pretty active one as he became the President of the acclaimed Pugwash Conference and a thought leader at coveted international entities like Stockholm Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), the Asia Pacific Leadership Initiative (APLN) and many more.

Interestingly, Jayantha Dhanapala began and ended his international career in a youth-inspired fashion. He was already an internationalist when as a 17-year-old he won the prestigious Herald Tribune competition for his writing titled ‘The World We Want’ that put him in touch with likes of young American Senator John F. Kennedy. Nearly a half a century later, he retired from national and international service to undertake the important mentoring job for yet another dynamic youth organisation in Sri Lanka—‘Sri Lanka Unites’, a live wire behind this book launch.

As this volume points out, human rights are not a Western concept. Sri Lanka therefore need not and cannot be defensive on human rights. They are in perfect harmony with our ethos, Buddhist and other. Our Constitution enshrines them. Our soldiers have bravely fought to restore them to apart of our country victimised by mono-ethnic terror. All countries are burdened with human rights issues in one form or other and Sri Lanka is no exception. What we need to do is to prevent those issues from migrating abroad due to our leaders’ inability or unwillingness to work together and reach a domestic consensus on accountability of the kind advocated, for example, by the LLRC. The process can thus be transformed from an intrusive and externally driven one to a locally driven consensual one. When human rights issues migrate abroad they become foreign policy problems, generally rendering the dialogue with certain foreign interlocutors contentious, if not adversarial. Sri Lanka is a case study on this score.

At the international level, he was acclaimed as a consensus builder. That appellation is quite consistent with the longstanding profile of Sri Lankan diplomacy seeking consensual outcomes in critical international endeavours, be it in the UNCLOS (Law of the Sea), the Indian Ocean as a Peace Zone (IOPZ), Common Fund for Commodities, the regulation of armaments etc.

Ambassador Dhanapala was the choice of the international community to be the President of the 1995 Conference on the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). After he guided that contentious Conference to a successful conclusion, the respected international journalist Barbara Crossett wrote in the New York Times “A star is born” to pursue consensual diplomacy. Jayantha Dhanapala in his customary modesty will of course be the first to disclaim any stellar status, but the journalist was simply acknowledging what was already obvious – his work had made its mark on the world stage.

When he was our Ambassador to the United National at Geneva, he led a diplomatic team that was able to steer the deliberations of the UN Commission on Human Rights to a consensual conclusion on the post 1983 situation in Sri Lanka. That was done without entailing the kind of controversial and even undeliverable obligations such as those in the last Resolution of HRC on Sri Lanka. It was executed professionally and appreciated institutionally. There were no roadside bill boards announcing victory or proclaiming triumphalism as was the case with some other Resolutions later.

Turning again to the substance of the book, given time constraints, I would comment only on two matters dealt with in the volume – human rights and disarmament/security.

Dhanapala’s critical comments about double standards in the international discourse on human rights is accompanied by his cogent observation that it would not be smart governance or smart diplomacy to portray human rights as a ‘white man’s burden’. This is of particular relevance at a time when Sri Lanka, under a new electoral mandate and a new President, searches for options to deal with the controversial decisions of the Human Rights Council in Genva. As the new Government explores options to review and possibly modulate the Resolution that enjoys the ill-advised co-sponsorship of the former Government, preventive diplomacy in Geneva and robust and independent functioning of the judicial and law enforcement processes at home would facilitate a co-operative, rather than contentious, way to deal with the UN in general and the HRC Resolution in particular.

As this volume points out, human rights are not a Western concept. Sri Lanka therefore need not and cannot be defensive on human rights. They are in perfect harmony with our ethos, Buddhist and other. Our Constitution enshrines them. Our soldiers have bravely fought to restore them to apart of our country victimised by mono-ethnic terror. All countries are burdened with human rights issues in one form or other and Sri Lanka is no exception. What we need to do is to prevent those issues from migrating abroad due to our leaders’ inability or unwillingness to work together and reach a domestic consensus on accountability of the kind advocated, for example, by the LLRC. The process can thus be transformed from an intrusive and externally driven one to a locally driven consensual one. When human rights issues migrate abroad they become foreign policy problems, generally rendering the dialogue with certain foreign interlocutors contentious, if not adversarial. Sri Lanka is a case study on this score. The Dhanapala commentary brings forth some home truths about this matter.

The bulk of the book is of course devoted to Jayantha Dhanapala’s seminal contributions to our national endeavours as well as international co-operation in the field of peace, security and disarmament.

The content is full of eloquent expressions as to why humanity should treat nuclear disarmament as a global question – even an existential one – and not a discretion reserved for a few bomb wielding states. He explains how sustained disarmament is fundamentally important to progress towards sustainable development for all nations, and why the world must make a choice between continuing the arms races or pursuing development, as it would obviously be untenable to try to pursue both at the same time. The commentary on the relentless militarisation of technology makes it clear that humankind is facing unprecedented dangers posed by the potential abuse of artificial intelligence, its weaponisation in particular.

Will ‘Artificial Intelligence’ (AI) escape the biological control of the human being and occupy the driving seats of war machinery? This is no idle science fiction fantasy. Two prestigious British universities have committed serious research resources to explore ways to counter this potential danger.

I wish the editors had included further work by Ambassador Dhanapala on this important subject. Artificial intelligence could represent a grave escalation in technology weaponisation affecting all countries, both rich and poor. Referring to the work of more than 3000 experts, he pointed out to an international conference more than three years ago, that the so called “AI weapons” do not require costly or hard to get raw materials, thus making them cheap and most likely to spread fast. Experts warned that those killing machines could end up in the hands of despots, terrorists and war lords. This indeed is a chilling prospect especially for smaller vulnerable countries – the so called soft targets – given our own experience in the horror of the Easter Sunday attacks a few months ago.

The much acclaimed Israeli scientist and historian Professor Yual Noah Harari in his latest work ‘21 Questions for The 21st Century’ says humankind is faced with three clear and present dangers, namely, nuclear war, climate change and the potential abuse of Artificial Intelligence.

These are the dangers that early responders like Jayantha Dhanapala tried to flag to the states and the internationals even before the work of the likes of Harari became headlines. It is both ironic and paradoxical that even as humans’ life expectancy expands, humanity’s own life expectancy seems to progressively contract, thanks to our wanton assault on nature, our unsustainable lifestyles and weaponisation of technology.

When our generation began its working life about half a century ago, our computing power was confined to the heavily wired crude calculator or the very noisy mechanical counting machine. The IT explosion that followed has now grown to an ever expanding array of powerful algorithms and super computers that are both mind-boggling and manipulative. Given our proven propensity to militarise technology and knowledge, the younger generation must manage these powerful tools with care, prudence and vision. The thoughts and words of Jayantha Dhanapala and Yual Hariri can come in handy.

Grandstanding is not a strong point for Jayantha Dhanapala. Many expected his memoirs but many also heard that he did not want to produce and market self-centred documents, or to “blow one’s own trumpet” as he puts it. The volume instead seeks to capture his insights, comments and interpretations on a broad range of issues of national and international relevance as seen by his editors.

On the whole, the volume carries a simple but stark message: International cooperation with broad-based participation is not a matter of choice but the imperative of our time. Neither disarmament nor human rights is a burden or a luxury of one particular group of countries because all of humanity has profound stakes in these challenges. The Dhanapala commentary illuminates choices available clearly.

I therefore thank the youth organisation that undertook this initiative, the editors who did a good job of contextualising the commentary and the affable Dhanapala family who supported the effort.

May I also thank you for your patience in listening to these random utterances.