Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Tuesday, 14 November 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

It would be a suicide mission for the Central Bank to undertake inflation target-based monetary policy without strictly enforcing budget discipline by the Government, as I cautioned in my article appeared in the Daily FT of 30 October (see http://www.ft.lk/columns/The-political-economy-of-central-banking-in-Sri-Lanka/4-642422). Although I anticipated it would spark a heated debate, several writers have expressed similar sentiments favouring my argument in their subsequent newspaper articles.

It would be a suicide mission for the Central Bank to undertake inflation target-based monetary policy without strictly enforcing budget discipline by the Government, as I cautioned in my article appeared in the Daily FT of 30 October (see http://www.ft.lk/columns/The-political-economy-of-central-banking-in-Sri-Lanka/4-642422). Although I anticipated it would spark a heated debate, several writers have expressed similar sentiments favouring my argument in their subsequent newspaper articles.

The point that I raised is that the Central Bank alone cannot tackle inflation whilst the fiscal authority, which is the Ministry of Finance, continues to fuel inflation by financing its budget deficit through bank borrowings. The problem becomes acute when such borrowing is obtained from the Central Bank, which is known as seigniorage. It causes an increase in the monetary base accompanied by new money printing and multiple expansion of the total money supply leading to speed up inflation. Hence, reduction of the budget deficit becomes crucial in inflation targeting.

Since the 1980s the Central Bank has been conducting monetary policy with a targeted monetary aggregate. Globally, monetary targeting is found to be problematic due to the instability between monetary aggregates and goal variables such as inflation. As a result, monetary targeting frameworks have been downplayed or abandoned in several countries.

A number of monetary authorities have begun to use inflation targeting for the conduct of monetary policy following the success in New Zealand which launched inflation targeting in 1990. Accordingly, the central bank assumes the responsibility of maintaining a pre-announced inflation target using a monetary policy tool such as interest rates. In this case, the Central Bank is totally accountable to keep inflation within the target. The success of inflation targeting depends on several factors. In particular, fiscal policy considerations should not dictate monetary policy.

The Central Bank is to embark upon a monetary policy framework in due course with an inflation target of 4-6% envisaging a decline in the budget deficit to 3.5% of GDP by 2020.Leaving aside the practical difficulties in attaining such an optimistic fiscal target, a disturbing feature in the Budget 2018 is that it makes no reference to the critical need of adhering to strict fiscal discipline in the context of the envisaged inflation targeting framework.

The theme of the Budget 2018 is ‘Blue-Green Budget: The Launch of Enterprise Sri Lanka’. In my opinion, fiscal rules aiming at inflation target-based monetary policy should have been the underlying theme of the present budget speech rather than peripherals such as ‘blue ocean’ and ‘green environment’ that are given prominence in the Budget speech, though they may be important in their own right.

But as far as macroeconomic stability is concerned, nothing is important than enforcing fiscal rules so as to bring down the budget deficit, which has given rise to multiple economic hazards – to name a few, inflation, high cost of living, low real interest rates, overvalued exchange rate, anti-export bias, import rise, balance of payments deficits, uncertain investment climate and asset bubbles.

The projected budget deficit for 2018 is 4.8% of GDP, according to the Budget speech. It is doubtful whether the actual budget deficit could be retained within this target next year, given the poor track record in the past and the possible spending spree with the upcoming elections. The projected deficit for 2017 was 4.7% of GDP as per last year’s budget speech, but the actual deficit has gone up to 5.2% of GDP.

A major reason for overstepping the deficit target is the accommodation of a large number of supplementary estimates each year to cover up huge amounts of additional expenditure, which were not in the original budget estimates. The most recent example is the seeking of parliamentary approval for supplementary estimates just two days ahead of the budget speech to the tune of Rs. 11,206 million to cover up the contingent liabilities incurred by several Ministries for foreign trips, vehicle maintenance, etc. A series of such supplementary estimates were approved this year for purchasing of new vehicles for parliamentarians and similar extravagant expenses.

In order to satisfy the voters so as to retain power at each election, politicians have a tendency to offer various welfare benefits to households such as handouts, cash transfers and food subsidies, and also to create jobs for them in the public sector. Such populist policy preferences invariably lead to raise the Government expenditure, budget deficit, public debt, money supply, inflation balance of payments deficits. The outcomes are high cost of living, food shortages, subsidy cuts and various other hardships. This is the kind of political culture nurtured in this country throughout the post-independence period.

By and large, the society has got accustomed to the habit of depending on such benefits provided by the Government to meet their basic needs. This dependency syndrome has led to inefficiency, corruption and various other economic ills pulling down the economy over the decades.

This process is continuing even now in the midst of the Local Government elections to be held soon. Just two days ahead of the Budget speech, for instance, the Government reduced import duties on selected food items – potatoes, big onions, dhal, dry fish and sprats.

Tax revenue is the main source of Government revenue accounting for 88% of the total receipts projected for 2018. The entire burden of fiscal improvement falls on indirect taxes imposed for goods and services consumed largely by the ordinary people. The additional tax revenue expected for 2018 is Rs. 285 billion, of which as much as Rs. 218 billion or 77% is to be collected from indirect taxes consisting of taxes on goods and services and tariffs on foreign trade.

The increased revenue to be generated from income tax in 2018 is only Rs. 67 billion accounting for 23% of the tax revenue hike. The generous tax concessions granted to investors and widespread tax evasion have restricted the growth of income tax revenue over the years.

As a result, the indirect tax component will continue to remain high at 82% of the total tax revenue in 2018, in contrast to the repetitive policy announcements made by the government to reverse the indirect to direct tax ratio to 60:40. The Government expects that the ongoing Inland Revenue reforms including the new Inland Revenue Act would raise the revenue in years to come facilitating fiscal consolidation.

The recurrent expenditure is expected to account for 75% of the total Government expenditure (15.8% of GDP) in 2018 leaving the balance 25% for public investment (5.4% of GDP).

As in the previous years, the bulk of the recurrent expenditure in 2018 will go to interest payments, salaries and wages, subsidies and transfers. The interest payments on accumulated public debt will be Rs. 820 billion. The widening fiscal deficits have compelled the successive governments to rely on extensive domestic borrowings and foreign commercial borrowings augmenting the debt service burden to unsustainable levels.

The expenditure on salaries and wages will amount to Rs. 705 billion next year. The Government’s wage bill has gone up mainly due to an unprecedented expansion of the public sector with a huge work force running into over 1.3 million employees. In other words, one person out of every 15 persons is a Government employee.

Welfare subsidies to households and transfers to loss-making State-Owned Enterprises amount to Rs. 507 billion. The populist concessions introduced in successive budgets have contributed to augment the subsidies and transfers continuously.

In 2018, the banking system will be compelled to finance as much as Rs. 120 billion accounting for 18% of the budget deficit. This figure is likely to go up further in the background of this year’s phenomenal increase in actual bank borrowings to the tune of 170 billion as against the original estimate of only Rs. 32 billion indicated in the Budget 2017.

A part of the anticipated bank borrowings will undoubtedly be raised from the Central Bank by way of printing new money causing a multiple rise in the total money stock. The expansionary financing by fiscal authorities goes against the Central Bank’s transition towards inflation targeting.

This brings us to the problem of fiscal dominance over monetary policy, in which the fiscal authority prepares the annual budget on its own compelling the Central Bank to finance the unbridged portion of the budget deficit by way of printing money so as to secure fiscal solvency. In such a situation, the space available to the Central Bank to conduct independent monetary policy is extremely limited, and as a result, inflation targeting becomes unviable.

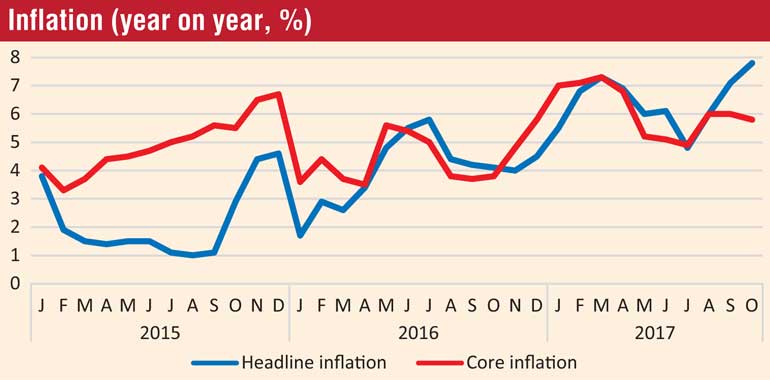

The expansionary borrowing by the Government from the banking system has been a major source of core inflation, which shows an increasing trend in recent years, as shown in the Chart. The core inflation, which is calculated by removing the temporary price effects of supply shocks from the headline inflation, reflects the underlying inflation caused by monetary factors.

The present fiscal consolidation initiatives are limited only to the revenue side leaving the expenditure side intact. Inflation targeting calls for robust fiscal policy reforms to reverse the fiscal deterioration not only by mobilising more revenue but also by rationalising the expenditure structure for which unwavering political commitment is imperative.

The Central Bank cannot fight a lonely battle against inflation. Its inflation targeting drive would become futile unless it is effectively supported by stringent fiscal rules with a long-term economic focus putting aside short-sighted political motives, as I reiterated in my previous columns. This approach is lacking in the present Budget speech too.

(The writer is Emeritus Professor, Open University of Sri Lanka.)