Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Saturday, 7 October 2017 00:34 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

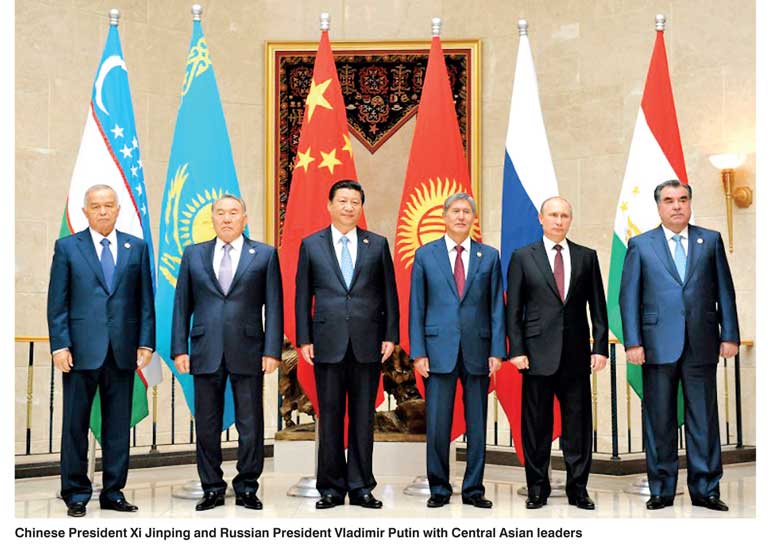

China and Russia are both trying hard to establish themselves in Central Asia for economic as well as politico-strategic reasons. Although China has thrown a lot of money into the region and has many high value projects to its credit, and Russia has had a long history of close association with the region as a constituent of the USSR, the going has not been easy for them.

China and Russia are both trying hard to establish themselves in Central Asia for economic as well as politico-strategic reasons. Although China has thrown a lot of money into the region and has many high value projects to its credit, and Russia has had a long history of close association with the region as a constituent of the USSR, the going has not been easy for them.

China’s instrument in the Central Asian region is the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) and Russia’s is the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU).

Though these two schemes have been devised for different reasons, and there is an element of rivalry built into them, they are not necessarily in conflict. They can be integrated. In fact, China wants such an integration, and Russia has expressed an interest in responding positively. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s participation in the One Belt One Road (OBOR) summit in Beijing in May 2017 was indicative of that.

The SREB is linked to the EEU through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) which has as its members Russia, China, India and Pakistan.

However, there is a subtle turf war going on at the same time. Russia feels that Central Asia is its legitimate strategic and economic backyard having been a key determining factor in it since Tsarist times. It would not be incorrect to say that the EEU is but a means to re-establish Russia’s control which it had lost because of the crack up of the USSR in 1991.

However, there is a subtle turf war going on at the same time. Russia feels that Central Asia is its legitimate strategic and economic backyard having been a key determining factor in it since Tsarist times. It would not be incorrect to say that the EEU is but a means to re-establish Russia’s control which it had lost because of the crack up of the USSR in 1991.

Russia sees good prospects of re-entry in the region because Central Asian countries (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan) still have friendly feelings towards it, sharing some cultural characteristics thanks to a long association. At the very least, in comparison with China, Russia is viewed in a more favourable light by Central Asians.

But in economic terms, China scores over Russia in Central Asia by its ability to pour money on a scale which Russia can never match. The Chinese also execute projects faster than the Russians.

China’s SREB

China’s economic flagship in Central Asia is the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB).It is part of the One Belt One Road Initiative (OBORI). The other part is the 21st Century Maritime Silk Route.

The Maritime Silk Route envisages the building of a string of ports linking China with Western countries through the Indian Ocean, and is meant to prevent vital sea lanes from being blocked by hostile forces like the US and Japan.

But the SREB is meant to provide an alternative land route from China to Europe, a route which had existed in ancient times.

The SREB, along with its developmental projects, is also meant to improve the economies of the Central Asian counties; reduce local frustrations; and prevent the population from taking to Islamic terrorism to vent their grievances against an uncaring world.

However, a more immediate and pressing objective of the SREB is to improve the economies of the Western regions of China like Xinjiang which are backward compared to the Eastern and Southern provinces. Frustrations with Han Chinese rule in Xinjiang have led to violent agitations.

With Muslim Uighurs being 46% of the population of Xinjiang, Islam and Islamic practices are matters of conflict with the mainstream Han Chinese. And being ethnic Turks, the Uighurs have ties with the Turks of Central Asia. Beijing’s control over Central Asia is therefore necessary to minimise Xinjiang’s potential to trouble Beijing.

Though China’s commitment to the SREB is a minuscule $ 3.5 billion as compared to $ 890 billion currently committed to the OBOR as a whole, projects worth several hundred million dollars have been signed with the Central Asian countries.

Among China’s major projects in Central Asia are the Moscow-Kazan high speed rail link, with a future plan to extend it to Beijing. China is very keen on building the Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor linking China to the Caspian Sea which is bounded by Kazakhstan to the North East, Russia to the North West, Azerbaijan to the West, Iran to the South, and Turkmenistan to the South East.

The China-Iran rail line materialised in February 2016, and in September the same year, a rail link was established between China and Afghanistan. . In August 2016, the China-Afghanistan train, hauling 100 containers of goods worth more than $4 million, reached Mazar-i-Sharif in Afghanistan, via Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. A single trip is 7,500 km long and takes 15 days, but it is half the time needed for maritime transportation.

China has already concluded $ 8 billion worth of deals in Kazakhstan including a 49% stake in a dry port. In June 2016, Chinese President Xi Jinping inaugurated a rail link between Ferghana Valley and Tashkent, funded by China’s Exim Bank as well as the World Bank.

By 2012, China had taken control of 25% of the oil produced by Kazakhstan and built the Kazakhstan-China pipe line. Turkmenistan uses the China-Central Asia pipeline to export gas.

Between 2013 and 2015, China had invested in several cement plants in Tajikistan. It built a power plant in its capital Dushanbe in 2016. China has also built a power transmission line linking north and south Kyrgyzstan.

Sinophobia

However, there is an ingrained anti-China or anti-Chinese feeling in Central Asia. While the power elite sees China as a source of much needed money for investment, the people see China as a threat. Sinophobia is palpable particularly in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Polls reveal that Russia is seen as a friend and China as a threat.

In Kyrgyzstan in 2011-12, there were complaints about Chinese managers ill-treating local workers. In 2015, there was violence between Chinese and Kazakh workers. There is also complaint that Chinese companies hire Chinese workers in preference to locals. The gap between the locals and the Chinese is made worse by the latter’s tendency to avoid mixing with locals.

Grant of scarce agricultural land to foreign, especially Chinese, companies, is a big issue in Central Asia. In 2016, there were agitations on the issue in several cities of Kazakhstan.

Getting projects by corrupt means is another problem plaguing Chinese investments in Central Asia. While China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) follows international norms, other Chinese companies and institutions, have been accused of entering into shady deals to swing plum projects.

This stems from China’s desperate need to get projects abroad to utilise excess capacities in its industries. But the Chinese may be having no option but to grease the palms of officials and ministers in developing countries given the fact that nothing will get done there unless under-the-counter payments are made.

China’s lack of concern for the environment in the developing countries is another cause of conflict. In 2012 in Kyrgyzstan, there was an agitation against a Chinese built cement plant. A US$ 300 million oil refinery ran into a storm on environmental grounds, as did a cement plant in Tajikistan.

One of the main grievances against Chinese investments is that they are not designed to meet the felt needs of local people. Projects are proposed, accepted and implemented for reasons other than the welfare of the common man from the point of view of that common man.

But China and Chinese companies are now revising the theory that deals with the elite or the power brokers of the recipient country are enough and public sentiment could be ignored. There is now a growing sense of corporate social responsibility.

The Chinese may also be rethinking on the policy of assuming that political stability is given, as it is in China. Experience has told them that governments and policies change in other countries, and that these may adversely affect Chinese projects.