Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday, 8 January 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A Sri Lankan think tank, Pathfinder Foundation, has drafted a Code of Conduct for nations in the Indian Ocean Region which are tackling threats to maritime security from “non-state actors” like terrorists, pirates, human and narcotics smugglers and those indulging in unauthorised and illegal fishing.

Realising the difficulties and complications involved in devising a comprehensive maritime security system in an atmosphere of great power rivalry and fears and suspicions between states in the region, the Pathfinder Foundation embarked on a task to devise a security system to tackle a bunch of threats which all countries face, namely, threats from “non-state actors”.

In fact, now, much of the problem in the seas is created by non-state actors. But nations, primarily concerned about fighting inter-state naval wars, are not equipped, trained and organised for fighting the small enemy, the intrepid and elusive non-state actor.

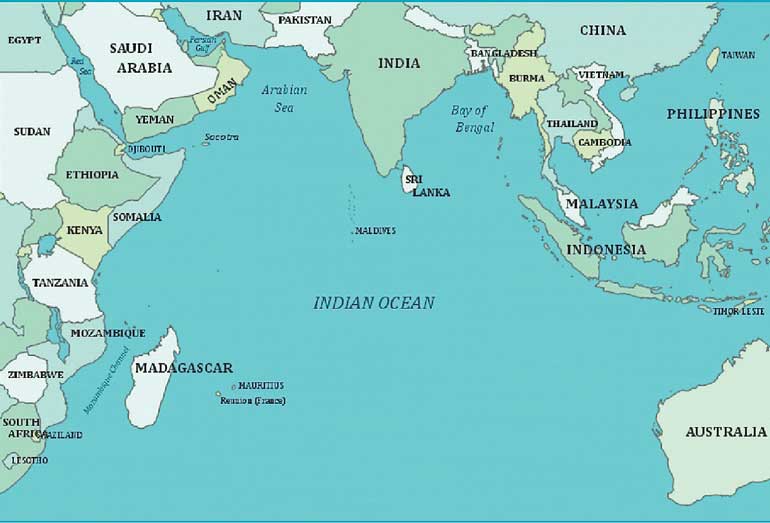

And the Indian Ocean is an area which is crying for protection from aggressive non-state actors. It is through the Indian Ocean that 70 % of world trade and 80% of the world’s maritime trade in crude oil passes. Therefore, ensuring security in these waters is of primary importance to all trading countries. The fact that the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) is thickly populated with 2.7 billion persons (35% of the world’s population), further heightens the need for security.

But ensuring security has been problematic, firstly because of great power rivalries, and secondly because of the existence of “chock points” such as the Strait of Hormuz, Bab el-Mandab and the Straits of Malacca.

Sri Lanka’s geographically central location in the Indian Ocean and its proximity to the major sea routes have, down the years, inspired its political leaders to be pro-active in initiating, from time to time, imaginative measures to ensure its security.

As early as 1971, the then Sri Lankan Prime Minister Sirima Bandaranaike along with the President of Tanzania, got the UN General Assembly to declare the Indian Ocean as a “Zone of Peace”. The declaration was adopted at the 26th session by 61 votes in favour, none against and 55 abstentions.

But efforts to implement the declaration were fruitless because the big powers as well as emerging regional powers kept using the ocean to build and buttress their power. The US, which had been the dominant power in the IOR, had abstained from the UNGA vote on the Zone of Peace. More recently, China’s expansionist policies under President Xi Jinping, and Indo-US resistance to the Chinese moves, have jeopardised security in the Indian Ocean. However, the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) has been at the task of devising a security system, and had designated Sri Lanka as the Lead Country to devise a maritime security system. But Pathfinder Foundation felt that it would be better to start work in an area where cooperation and consensus could be obtained more easily and that area is the threat to all from non-state actors, Adm. Dr. Jayanath Colombage, the maritime security expert at the Foundation said.

The Foundation has drafted a “Code of Conduct” which is now being circulated for comments and suggestions. The Code of Conduct, unlike the 1982 UN Convention of the Law of the Sea, will not be a legally-binding document, but would prescribe rules to be observed in organising cooperation in the pursuit of a common set of objectives. It is the first step towards creating a binding convention, Adm. Colombage said.

Pathfinder Foundation’s effort has the full backing of the Sri Lankan Government. Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe had said in his speech at the Deakin University in February 2017 that any maritime security agreement, “needs to recognise the escalation in human smuggling, illicit drug trafficking and the relatively new phenomenon of maritime terrorism.”

Wickremesinghe was backed by Indian Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj at the 2nd Indian Ocean conference in Colombo in September 2017. She said: “The Indian Ocean is prone to non-traditional security threats like piracy, smuggling, maritime terrorism, illegal fishing, and trafficking of humans and narcotics. We realise that to effectively combat transnational security challenges across the Indian Ocean, including those posed by non-state actors, it is important to develop a security architecture that strengthens the culture of cooperation and collective action.”

Code of Conduct

The following are the main objectives of the Code of Conduct (CoC): sharing and reporting relevant information; interdicting ships and/or aircraft suspected of engaging in transnational organised crime in the maritime domain, maritime terrorism, Illegal, Unauthorised and Unregulated (IUU) fishing and other illegal activities at sea; ensuring that persons committing or attempting to commit in transnational organised crime in the maritime domain, maritime terrorism, IUU fishing and other illegal activities at sea are apprehended and prosecuted; and facilitating proper care, treatment, and repatriation of seafarers, fishermen, other shipboard personnel and passengers subjected to transnational organised crime in the maritime domain, particularly those who have been subjected to violence. The CoC has said that signatories should carry out their obligations and responsibilities under it in a manner consistent with the principles of sovereign equality and territorial integrity of states. Non-intervention in the domestic affairs of other States is a must; The CoC should not violate the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982.

Operations to suppress transnational organised crime in the territorial sea of a signatory (a country which has signed the CoC) are the responsibility of, and subject to, the sovereign authority of that signatory.

The signatories should ensure that, in seeking the fulfilment of the above objectives, a balance is maintained between the need to enhance maritime security and facilitation of maritime traffic and to avoid any unnecessary delays to international maritime trade when navigating through the Indian Ocean.

Measures at national level

The signatories should develop and implement: (a) appropriate national maritime security policies to safeguard maritime trade from all forms of unlawful acts; (b) bring about national legislation, practices and procedures, which together provide the security necessary for the safe and secure operation of port facilities and ships at all security levels; and (c) national legislation which ensures effective protection of the marine environment.

The signatories should establish a national maritime security committee or a system for coordinating activities between departments, agencies, control authorities, and other organisations of the government, port operators, companies and other entities concerned with, or responsible for the implementation of, compliance with, and enforcement of, measures to enhance maritime security and search and rescue procedures.

The signatories should establish a national maritime security plan with related contingency plans (or other systems) for harmonising and coordinating the implementation of measures designed. The signatories should prosecute, in their domestic courts, and in accordance with relevant domestic laws, perpetrators of all forms of piracy and unlawful acts against seafarers, ships, port facility personnel and port facilities.

The CoC says that the organisation and functioning of this national system is exclusively the responsibility of each State, in conformity with applicable laws and regulations.

Protective measures for ships

The signatories should encourage states, ship owners, and ship operators to take protective measures against transnational organised crime in the maritime domain, taking into account the relevant international Conventions, Codes, Standards and Recommended Practices, and guidance adopted by the International Maritime Organization (IMO).

Tackling piracy

The CoC says that the signatories should extend the fullest cooperation for (a) arresting, investigating, and prosecuting persons who have committed piracy or are reasonably suspected of committing piracy; (b) seizing pirate ships and/or aircraft and the property on board such ships and/or aircraft; and (c) rescuing ships, persons, and property subject to piracy.

Limits to hot pursuit

A signatory may seize a pirate ship beyond the outer limit of any state’s territorial sea, and arrest the persons and seize the property on board. Any pursuit of a ship, where there are reasonable grounds to suspect that the ship is engaged in piracy, extending in and over the territorial sea of a signatory is subject to the authority of that signatory. No signatory should pursue such a ship in or over the territory or territorial sea of any coastal State without the permission of that State, the CoC says.

Consistent with international law, courts of the signatory which carries out a seizure, may decide upon the penalties to be imposed, and may also determine the action to be taken with regard to the ship or property, subject to the rights of third parties acting in good faith.

The signatory which carried out the seizure, subject to its national laws, and in consultation with other interested entities, waive its primary right to exercise jurisdiction and authorise any other signatory to enforce its laws against the ship and/or persons on board.

Unless otherwise arranged by the affected signatories, any seizure made in the territorial sea of a signatory should be subject to the jurisdiction of that signatory.

Embarked officers

A signatory may nominate law enforcement or other authorised officials (called embarked officers) to embark in the patrol ships or aircraft of another signatory (called host signatory). The embarked officers may be armed in accordance with their national law and policy and the approval of the host signatory.

When embarked, the host signatory should facilitate communications between the embarked officers and their headquarters. Embarked officers may assist the host signatory and conduct operations from the host signatory ship or aircraft if expressly requested to do so by the host signatory, and only in the manner requested. Such a request may only be made, agreed to, and acted upon, in a manner that is not prohibited by the laws and policies of both signatories.

Asset seizure and confiscation

Assets seized, confiscated or forfeited in consequence of any law enforcement operation pursuant to this code, undertaken in the waters of a signatory, should be disposed of in accordance with the laws of that signatory.

To the extent permitted by its laws and upon such terms as it deems appropriate, a signatory may, in any case, transfer forfeited property or proceeds of their sale to another signatory or an inter-governmental body specialising in the fight against maritime crime.

Coordination/information sharing

The CoC says that each Signatory should designate a national focal point to facilitate coordinated, effective, and timely information flow among the signatories. In order to ensure coordinated, smooth, and effective communication between their designated focal points, the signatories should use the piracy information sharing centres.

Each Centre and designated focal point should be capable of receiving and responding to alerts and requests for information or assistance at all times.

Incident reporting

The signatories should undertake development of uniform reporting criteria in order to ensure that an accurate assessment of the threat of piracy and armed robbery in the Indian Ocean is developed taking into account the recommendations adopted by IMO.

Consistent with its laws and policies, a signatory conducting a boarding, investigation, prosecution, or judicial proceeding pursuant to this CoC should promptly notify the results thereof to any affected flag and coastal States and the Secretary-General of the International Maritime Organization and the Secretary General of Indian Ocean Rim Association.

The signatories’ National Centres should (a) collect, collate and analyse the information transmitted by the signatories and (b) prepare statistics and reports on the basis of the information gathered.

Cooperation

A signatory may request any other signatory, through the centres, or directly, to cooperate in detecting criminal and unauthorised activity. Cooperation, as appropriate, may be undertaken as determined by the signatories concerned.

A signatory may request any other signatory, through the centres, or directly, to cooperate in detecting crimes. A signatory may also request any other signatory, through the centres or directly, to take effective measures in response to reported transnational organised crime in the maritime domain.

Co-operative arrangements such as joint exercises or other fours of cooperation, as appropriate, may be undertaken as determined by the signatories concerned.

Legal action

Signatories are encouraged to incorporate in national legislation, transnational crimes in the maritime domain, as defined in Article 1 (3) of this Code of Conduct, in order to ensure effective indictment, prosecution and conviction in the territory of the signatories.

Dispute settlement

Signatories should settle by consultation and peaceful means amongst each other any disputes that arise from the implementation of this CoC.

Within three years of the effective date of the CoC, the signatories should to consult, at the invitation of the Inter-Regional Coordination Centre to: a) eventually transform this Code of Conduct into a binding multilateral agreement; b) assess the implementation of this Code of Conduct; c) share information and experiences and best practices; d) Review activities which National Maritime Security Centre; e) review all other issues concerning maritime security in the Indian Ocean.

Claims

Any claim for damages, injury or loss resulting from an operation carried out under this CoC should be examined by the signatory whose authorities conducted the operation. If responsibility is established, the claim should be resolved in accordance with the national law of that signatory, and in a manner, consistent with international law.