Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Monday, 18 January 2021 00:30 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The great shrinkage of young people and old people taking their place is a dangerous signal because it portends an ominous old-age social security issue for all Sri Lankans. It is like a time bomb now clicking for the reach of the explosion level in every passing second. Unless it is addressed today, all Sri Lankans are set to meeting its bitterest consequences – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

Sri Lankans are ageing fast

Sri Lankans are ageing fast

Prime Minister and Minister of Finance Mahinda Rajapaksa in the Budget 2021 had made two proposals relating to old-age social security of people. One is for the introduction of a contributory pension scheme for the self-employed. The other is to extend the retirement age of workers covered under the Employees Provident Fund or EPF up to 60 years.

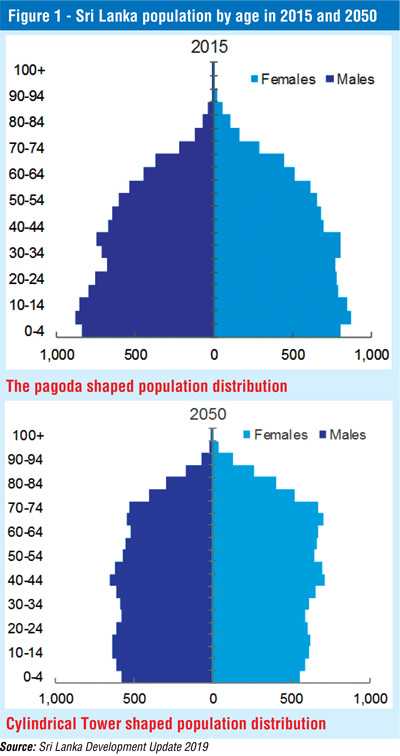

Both are marginal improvements in the present system and from that point are desired. However, they are short of the actual requirement of the old-age security of the Sri Lankans who are aging fast. According to the Sri Lanka Development Update, released by the World Bank in February 2019, the traditional triangular shape of Sri Lanka’s population pyramid began to change its shape in 1990.

Says the World Bank: “Its base, representing the young cohorts of the population, was already shrinking. This trend became more apparent in 2015, with both the body where the middle-aged population (or working-age population) and the elderly were already gaining significant mass. By 2050, it is expected that this process will translate into a further narrowing of the base and an evening out of the relative weight of the different age brackets, which will result in the pyramid taking a more rectangular shape. The number of elderlies is expected to catch up and then exceed the number of young children.”

This great shrinkage of young people and old people taking their place, presented in figures 1 and 2, is a dangerous signal because it portends an ominous old-age social security issue for all Sri Lankans. It is like a time bomb now clicking for the reach of the explosion level in every passing second. Unless it is addressed today, all Sri Lankans are set to meeting its bitterest consequences.

IPS: Gaps in the present pension schemes

Five years ago in 2015, two researchers attached to the Institute of Policy Studies or IPS, Shanika Samarakoon and Nisha Arunatilake, had warned Sri Lanka’s policy makers of this eventual catastrophe in a report titled ‘Extending Adequate Pensions for all in Sri Lanka – where are the gaps?’

The report, completed under the auspices of the International Labour Organisation or ILO, had considered the projected demographic changes in Sri Lanka in the next 40 years or so and compared what should be the desirable system which the country should have considering the present system of income security in the country.

Sri Lanka had had a plenty of pension schemes introduced from time to time. They have been fully or to a large extent funded by either the taxpayers or the employers of the affected workers. Samarakoon-Aruntilake had identified 16 of such schemes prevailing in the country and 12 of them had been introduced since independence. Out of them, six schemes had been introduced during the last 10-year period. But, all these schemes, except EPF and ETF, have not been self-supporting, needing heavy government subsidies to keep them floating.

Furthermore, even when all these schemes are lumped together, they do not provide adequate social security to the ageing population of the country. Hence, the due had proposed the introduction of a universal pension scheme covering those employed in the formal public and private sectors as well as those in the informal sectors.

A holistic social security system is the need of the day

Many analysts are of the opinion that Sri Lanka should have an income security system for the old. Income security is a narrow concept. A much broader one would be to look at the social security of the ageing population. Income security assumes that if one has money income, one can afford to have everything he desires once he becomes old and feeble. It then presupposes that there is a market system that would keep supplying all his requirements at the old age.

Social security on the other hand looks at social protection of old people at every stage. That protection encompasses social networks that would care, love, and take control of old people who are otherwise unable to attend to their own requirements.

In a traditional culture, this is done by the family and kinship system in society. In such a system, a two-way family relationship is built. The old people look after the offspring of their offspring till such time they are physically capable of doing so. Once they become feeble, their own offspring or the offspring of their offspring would look after them. All their needs – foods, shelter, clothing, healthcare, and spiritual enlightenment – are provided through the family support system. This is a sustainable system with no guilty feeling on either side. Each side helps each other through a social bond which is inviolable in terms of the ethos and norms of society.

Breakdown of the traditional social security system

However, this system has partly broken down mainly due to the entry of female offspring to labour force. It is partly because one side of the social bond still operates. That is, old-aged parents still support their offspring to bring up their grandchildren. This is an important contribution made by them in a background where services of caring and protective housemaids have become increasingly expensive. Thus, female workers have been able to contribute to the national economy by supplying their labour due to the in-house production of maids’ services by parents.

However, when parents become feeble and are no longer able to make a positive contribution to the family unit, looking after them becomes an extremely difficult task for children who had once got their free services to bring up their children. They are being constrained by lack of adequate time as well as lack of adequate income. In the current labour market system, children, if they desire, make available their time for feeble parents only by under-producing at workplaces.

But the market system does not permit them to do so. To hire nurses to look after feeble parents, they must work more to earn the needed income. That is not a viable option because their time is then not available not only for the feeble parents but also for the other family members. In such a situation, ensuring adequate income security for people who are ageing becomes a crucial necessity.

Key issues

But there are three issues in developing such a system. One is who would bear the cost. Another is how it could be made sustainable and viable. The third is how it could be managed with least cost to society and those who fund it.

Savings a must

In any society, the viable and sustainable method of ensuring social security is to get the people to save enough for the old age. This is consistent with life cycle income theory in which the income over time is posited to move in the fashion of an upturned U curve. This is due to the higher productivity in the young age and lower productivity in the old age.

However, the consumption grows steadily over time generating a surplus when the productivity is high and a deficit when the productivity slows down. Hence, the challenge for the market system is to collect the surplus into a long-term investment so that it would be available for use when the person reaches the old age.

There are some pockets of people in society who would resort to this tactic to safeguard their own old age. But that is rare and it presents an exclusive system of old age income security. What is needed is an inclusive saving system so that all those at young age would save for their old age. But the challenge is how to incentivise the young to get into long-term saving and investment.

Loss of family support

This was not a problem in traditional societies where savings were valued as a social habit. To some extent, this is true even today for the Chinese and the Japanese who are reported to be notorious savers. However, in Sri Lanka, there are two developments – one long-standing and the other emerging – which would impede society’s desire to make long-term savings for old age. The long-standing one is the obviation of the necessity for making savings for the old age because the government was supposed to meet that once a person becomes old.

Further, the universal supply of education and health care through community funding too made it unnecessary for a person to save for himself or the other family members. The emerging one is the emergence of the generation called Generation Y which is pro-consumption even at the expense of others. They expect parents and governments to meet all their current as well as future requirements. Hence, to build up systems where individuals would save for themselves have become a challenging issue.

Freak interest rate policies of governments

Governments’ interest rate policies too have impeded the long-term savings habits of people. All governments in Sri Lanka since independence, except in 1954 and 1955, have been running state affairs with deficit budgets.

To cut the interest costs to the government when they borrow money from the market, interest rates have been kept deliberately at a low level. If there was pressure for the interest rates to go up due to perceived high inflation expectations, the rates were moderated by meeting the governments’ financing requirements through the central bank. The result was self-defeating since it further augmented the inflation expectations and dried up even the available savings flows. Hence, governments had to get the central banks to print more and more money to supply itself with needed funds and it exacerbated the prevailing inflationary-savings situations.

This is where Sri Lanka today and it has forced the government to introduce various types of pension schemes targeting both the formal and informal sector workers, fully or to large extent, funded by the taxpayers or employers.

MMT and money printing

The present Government which follows the breakaway economic ideology called Modern Monetary Theory or MMT is in full use of the banking sector funds under a subjugated interest rate environment. Its own follies relating to tax reforms have cut deep into its revenue base.

During the first nine months of 2020, Government’s tax revenue has been lower by Rs. 386 billion compared to its record in the previous year. When prorated, this amounts to a loss of Rs. 514 billion during the full year. At the same time, government expenditure has ballooned partly due to the COVID-19 pandemic related expenditure programmes and partly due to its own policies that had been introduced without regard for income requirements. The gap has been filled by resorting to borrowing from the banking sector.

According to the Central Bank data, during the first 11 months of 2020, its borrowings from the banking system, that is, from the Central Bank and commercial banks, have increased by Rs. 2,019 billion. Of this, borrowings from the Central Bank alone have been at Rs. 437 billion. When the borrowings of the public corporations from commercial banks are added to the central government’s borrowings, the total public sector borrowings have amounted to Rs. 2,548 billion. At the same time, interest rates have nearly halved making consumption preferable to saving. This will adversely affect the saving for the old age as well.

Sustainability of pension schemes

This gives rise to the second issue, namely, the sustainability of the pension schemes in operation. If pension funds are to be supplied by persons other than those direct beneficiaries, there is always incentive for them, no matter whether it is the government or the private sector, to avoid the responsibility. Governments do not allocate adequate money in time to make the pension schemes viable.

A good example is the unfunded public servants pension scheme which is being funded by current and future taxpayers through a ‘Pay-As-You-Go’ system. Estimates by various analysts have put the unfunded gap in the pension scheme between Rs 1500 to 2000 billion. If the government decides to fund in one go, it will amount to about 10-13% of current GDP. Obviously, the current financial position of the government does not allow it to do so. In the case of both EPF and ETF, the scheme has acted as a tax levied on the private sector.

Hence, in the absence of an effective supervisory system, private sector enterprises are forced to evade the payments through devious methods. The result is the non-accumulation of a sufficient amount of funds in the system to gain capability of meeting the on-time financial obligations.

Management of pension systems

The management of pension schemes to provide an efficient service to beneficiaries is the third issue. In schemes which basically depend on manual methods, the costs have become enormously high on one hand and service efficiency low on the other.

Hence, digital systems in which the whole range of operation of the system must be computerised have become the necessity of the day. This is not a serious issue since there are already systems available off the self. All that is needed is to acquire and customise them. There will be teething problems in view of the need for training officers to operate, upgrade and maintain the systems. However, such problems are time-bound and would disappear over time.

With 16 different pension schemes in operation in Sri Lanka today, there is duplication of the work. It is necessary to amalgamate all these schemes into a general social security board that would operate on high technology to cut the management costs and provide an efficient service.

Hence, the necessity today is to have a holistic social security system rather than attempting at piecemeal solutions.

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected] )