Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Wednesday, 30 May 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

You may have heard that Sri Lanka is intent on drumming up more Foreign Direct Investments up to $ 5 billion by 2020. At the same time, the Government aims to improve the lives of Sri Lanka’s citizens by generating one million new and better jobs.

This isn’t a pipedream. Thanks to its many advantages, like a rich natural resource base, its strategic geographic position, highly literate workforce, and fascinating culture, the island nation is ripe for investment in sectors such as tourism, logistics, information technology-enabled services, high-value added food processing, and apparel.

What is Foreign Direct Investment and why does Sri Lanka need it?

Very simply, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is an investment made by a company or an individual in a foreign country. Such investments can take the form of establishing a business in Sri Lanka, building a new facility, reinvesting profits earned from Sri Lanka operations or intra-company loans to subsidiaries in Sri Lanka.

The hope is that these investment inflows will bring good jobs and higher wages for Sri Lankan workers, increase productivity, and make the economy more competitive.

Sri Lanka’s Government has recognised the need to foster the private sector and beef up exports to attain the overarching objective of becoming an upper-middle-income economy.

Attracting more FDI can help achieve that goal and fulfil the promise of better jobs.

Here’s five reasons why:

FDI and domestic investment are at the heart of economic growth

FDI could help accelerate Sri Lanka’s arrival at upper middle-income country status. Annual real GDP per capita growth averaged a bit above 4% in Sri Lanka over the past three decades. Accelerating this to 6% would speed up reaching upper-middle-income status – imagine reaching Singapore standards of living roughly a generation early. To get there, higher investment is needed.

FDI can boost economic growth

In many developing countries, FDI has overtaken aid, remittances, and portfolio investment as the largest source of external finance. In 2017, public sector investment in Sri Lanka was at an all-time high. However, Sri Lanka’s public investment is still low when compared to its peers. The island’s fiscal budget is rigid with almost 60% of the expenditure being pre-determined. Public investment is low and private investment needs to take up its share of the burden. FDI and private investment from domestic sources can help accelerate growth and create jobs.

FDI can drive technology exchange and innovation

FDI can enable the introduction of new technologies and innovative ways of production and service provision, which can then be replicated by local firms increasing their productivity and competitiveness, and plugging them into domestic and global value chains.

Particularly useful could be establishing innovation partnerships between firms in developing countries who have much in common and can easily transfer production and managerial strategies that are relevant to their country context.

FDI can diversify and increase exports

Boosting exports can help with the trade balance – Sri Lanka has had a persistent problem with its trade deficit. In addition, FDI here has largely been concentrated in traditional sectors with the composition of Sri Lanka’s basket of exported goods having remained largely unchanged for around 25 years.

Greater FDI would enhance the access of Sri Lanka’s producers to global production networks and facilitate the development of new activities within existing value chains, thereby increasing added value in production and accelerating economic growth. It would also diversify the economy’s composition as new sectors are introduced alongside traditional sectors, making Sri Lanka more resilient to external shocks.

New investments can help with Government revenue and foreign exchange reserves

FDI also helps governments boost tax revenues, providing the space for reduced borrowing — Sri Lanka’s borrowing is high — or for further budget spending on social benefits such as health and education. Since FDI comes in foreign-denominated currency, it is always useful in a country with external borrowing.

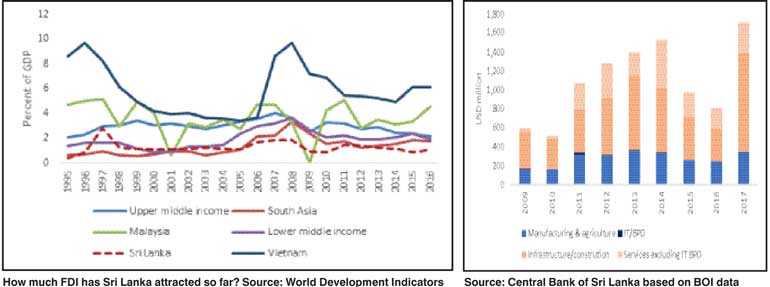

For now, FDI into Sri Lanka has been lower than in peer countries despite its location and access to major markets – hovering at less than 2% of GDP, as compared with Malaysia and Vietnam, for example.

To keep and increase FDI flows, Sri Lanka will need to make concerted and ambitious efforts to address gaps and play to its strengths.

Six ways Sri Lanka can attract more foreign investment

Sri Lanka’s war derailed the country’s growth. Before 1983, companies like Motorola and Harris Corporation had plans to establish plants in Sri Lanka’s Export Processing Zones. Others including Marubeni, Sony, Sanyo, Bank of Tokyo, and Chase Manhattan Bank, had investments in Sri Lanka in the pipeline in the early 1980s. All this changed after riots convulsed the country. The companies left and took their FDI with them.

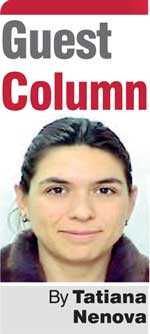

Nearly a decade after the civil conflict ended in 2009, Sri Lanka is now in a very different place. In 2017, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into Sri Lanka grew to over $ 1,710 million including foreign loans received by companies registered with the BOI, more than doubling from the $ 801 million (1) achieved the previous year.

Still, Sri Lanka can attract more FDI than 2% of its GDP – compare with Malaysia at 3-4% and Vietnam at 5-6%. FDI into Sri Lanka has been also, more importantly, skewed away from high value-added global production networks (see Figure).

The larger share of FDI inflows have been focused on infrastructure, which helps with jobs and growth temporarily during the construction period but not over the long term – compare a factory or a new IT service firm which would employ people as long as it makes profit, and export, pay taxes, and contribute to Sri Lanka’s growth for decades.

Moreover, high infrastructure FDI relies on few and large infrastructure deals that are unlikely to be replicated sustainably over time. Manufacturing and services hold a better promise for the long run, but even there, a large share of FDI is related to traditional sectors and local market-oriented activities with low value-added, where productivity gains are small. Only a relatively small proportion in export-oriented manufacturing and service activities, reaching sectors of the economy that are associated with global production networks.

To keep and increase FDI flows, Sri Lanka will need to make concerted and ambitious efforts to address gaps and play to its strengths. Simply put, Sri Lanka can improve FDI by having a more hospitable environment for investments. Taking steps in this direction is essential for domestic investment as well, not only FDI. GoSL reforms have already begun targeting problem areas, but more is needed. Here are six areas Sri Lanka has to focus on to improve FDI:

Reworking trade policy

Reforms in Sri Lanka’s trade policy saw eliminations or reductions of some 1200 para-tariff lines in late 2017, and further liberalisation is expected with the Budget in 2018 and beyond with a view to boost trade. More trade will help diversify the economy and exports, and lift a burden off of the public sector to drive growth. It can also actively promote technology absorption, skill upgrading, and increased competitiveness; workers, consumers, producers and the state will benefit in the long-run as a result.

Improving logistics and trade facilitation

Sri Lanka can leverage its unique location and trade agreements to overcome the diseconomies of its small scale. The Colombo Port, which already sees 80% of its volume come from transhipment cargo, is poised to grow. However, Sri Lanka cannot take its position for granted with high growth in other ports in Pakistan and India.

Another way to compete is on speed and cost of trade processing. While domestic logistics are inefficient, internationally Sri Lanka is performing better. Currently, it ranks 57.7 out of 100 on the BMI Logistics Risk Index, and places 15th on the UNCTAD Liner Shipping Connectivity Index, which ranks countries according to their level of connectedness to international maritime networks.

The per-container cost for exporting and importing to and from Sri Lanka are much lower than the South Asia average but not at world class level (respectively, $ 560 and $ 690 – South Asian average is $ 1,923 and $ 2,118, 2015 data). To go the extra mile to a regional logistics hub, the Government has started reforms including establishing a Trade Information Portal and the National Single Window which will streamline trade processing across the 20-plus agencies involved.

Promoting investments and enabling regulations while avoiding policy uncertainty

The island was ranked 111th out of 190 economies in the Ease of Doing Business Index 2018 which shows opportunity for improvement. The Government has carried out some focused reforms since 2016 to improve investment climate, and with the expected lag, reforms are cropping up. In 2017, trade across borders was made more efficient, and this year improvements are expected relating to starting a business, property registration and construction permits.

Reforms are needed to address critical challenges in areas like land ownership. Currently, land is primarily state-owned in Sri Lanka, and land administration is weak and cumbersome. Anecdotal evidence points to discouraged FDI projects due to land issues. A large share of exports and most export innovation has occurred in a few Export Processing Zones, primarily in the Western Province, that are now generally at capacity, new SEZs are being planned. Further water treatment capacity in SEZs is also needed. Some reforms are planned in foreign ownership (and one already passed in 2017 but more needs to be done).

Further, the BOI (the main FDI facilitation body) is being actively reoriented towards modern investment promotion. Internal Revenue Act streamlined and improved the efficiency and transparency of incentives applicable to foreign investments in Sri Lanka. GoSL is also liberalising the foreign exchange controls.

Policy uncertainty in Sri Lanka has proven daunting for investors, with a lack of information on regulations, high fragmentation in policymaking, frequent policy changes and slow policy implementation. Long-term policy strategies can serve as path-setters and expressed commitment to policy continuity in support of the GOSL vision.

Boosting innovation by way of competitive product and financial markets

Sri Lanka has seen little transformation in what it exports over the last 20 years. There’s been limited innovation and diversification even into “nearby product” space (new products closely related to existing ones) which is an easier step that happens organically with investment. This difficulty moving into new space has also left the country out of step with regional and global production networks. Where innovation exists, it has been limited to a handful of industries. A national innovation strategy seeks to address gaps and support start-ups and SMEs.

Financial products have also remained behind the firm needs – e.g. SMEs need factoring and leasing, supplier finance mechanisms and export-related financial instruments. Now the Secured Transactions Act is being amended to allow one of those innovative products – the use of movable collateral.

Addressing labour related issues and getting women to work

Efforts are also needed to expand the pool of labour, relax constraints in labour laws such as long and costly termination procedure, and equip Sri Lankans with skills in demand in the marketplace. In particular, Sri Lanka can benefit tremendously from boosting its female labour force participation rate – that can be done for example by addressing issues such as a lack of quality childcare, skills mismatch, unsafe transport and poor working conditions that keep women away from the labour force.

Sri Lanka could also ease the access of local companies to foreign expertise through introducing simpler visa procedures, which are currently complex and burdensome for foreign employees in Sri Lanka, limiting FDI especially for smaller ventures such as in tourism.

Providing enabling logistics and the right infrastructure environment

Nationally, Sri Lanka needs to address transportation shortfalls, which have seen inequitable development with some regions disconnected from growth, increasing issues of congestion, and poor safety for women. Different areas face different transportation gaps in roads, air travel and marine transportation infrastructure while rail infrastructure is outdated and limited, especially for the transport of goods.

Tatiana Nenova is a Program Leader for Sri Lanka and Maldives at the World Bank, responsible for financial markets, trade and competitiveness, macro and fiscal, governance, and poverty. Her operational work has focused on several financial sector areas of work (capital markets, access to finance for the poor, housing finance, and infrastructure finance and PPPs) as well as investment climate and institutions, trade policy and facilitation, and public sector institutions strengthening, and macro/fiscal policy. Before Sri Lanka, she has worked as Program Leader in Indonesia, with the World Bank CFO, as operational staff in South Asia, in the International Finance Corporation and in academia. Dr. Nenova has also published in leading US and international journals and co-created several innovative World Bank publications such as the Doing Business Report. She holds a Ph.D. in Economics from Harvard University.

Footnote:

1 These figures includes loans, excludes inflows to non-BOI companies and direct investment in listed companies in the CSE not registered with the BOI