Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Thursday, 12 July 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The recently-published ‘Sri Lanka Development Update 2018’1 by the World Bank focuses on creating more and better jobs for an upper middle-income Sri Lanka. It usefully analyses the state of Sri Lanka’s labour market and identifies challenges to attaining this development goal. The World Bank report’s deep dive into the issue of women’s labour force participation in Sri Lanka, including in post-conflict areas, is particularly thought-provoking. The report also reiterates the World Bank’s usual macroeconomic narrative about slow growth and lacklustre progress in economic reforms.

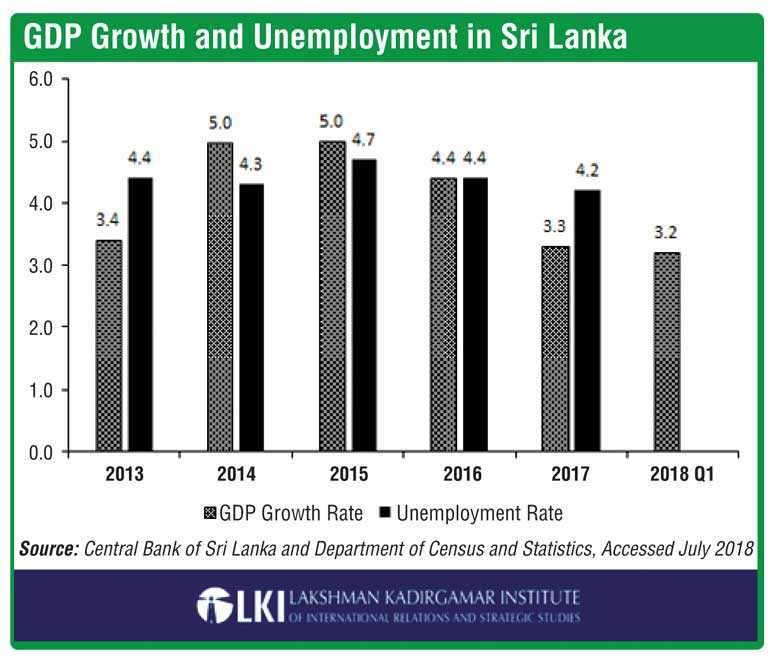

In my view, Sri Lanka’s experience does not tally with the typical Arthur Lewis model, in which surplus labour moves from the low-productivity rural sector to drive the expansion of a high-productivity modern sector. Today, Sri Lanka has a paradoxical combination of slow growth (3.2% in the first quarter of 2018)2 and labour scarcity (a low unemployment rate of 4.2% in 20173). A tight labour market means that the private sector is increasingly starved for skilled labour. Although several international and domestic factors are shackling Sri Lanka’s growth, the labour market deserves special attention. The time is ripe for a few well-implemented measures to increase labour market flexibility and boost growth. The private sector has to raise its game too.

Four kinds of labour market issues merit serious discussion in Sri Lanka. First, the World Bank report rightly identifies the need to raise female participation rates to increase Sri Lanka’s labour supply amidst its transition to an aging population. Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen candidly observed that investing a dollar in girls’ secondary education provides the best social return4 on development finance. In this vein, Japan is trying to increase female participation rates as a part of the so-called “Abenomics” structural reforms. Affordable child care is a key need, including in subsidised nurseries at large private firms and community-run crèches at the village-level, to encourage mothers to return to work. The top Sri Lankan firms should unilaterally set the example and others are likely to follow. Another need is ending harassment of women at the workplace and on transport through a “#MeTo” social media movement, with compulsory workplace training in both the private and public sectors.

Second, while the mismatch in available and required skills in the private sector is mentioned in the World Bank report, a missing issue is the poor English language ability of workers, which hampers labour productivity in the country’s growing services sector. When wages rose in Bangalore’s global IT hub a decade ago, Indian firms did not come to neighbouring Sri Lanka, partly due to a shortage of ample supplies of English speaking graduates. Instead, Indian IT firms went to the Philippines to set up shop.

The language problem is compounded by a lack of competent English teachers. A radical solution from East Asia is to import low-cost but competent English teachers from the Philippines on short-term work visas under a technical cooperation arrangement. A similar scheme may be developed for importing Chinese teachers given a growing Chinese tourist and investor presence in Sri Lanka and a dearth of Chinese-speaking local workers and managers.

Third, the World Bank report discusses the unemployment of arts graduates. Almost half (48%) of university graduates in 2016 were from an academic programme in the arts.5 This indicates a poor return on costly educational investments at the tertiary-level and a source of social distress, which have propelled two youth insurrections in Southern Sri Lanka. As a part of their recruitment efforts on university campuses, the private sector should offer paid internships during university holidays, to provide a taste of what it really means to work in a competitive business. These internships should also become a compulsory part of all degree courses. University careers services should be properly resourced and forge links with the private sector and State institutions.

Furthermore, charging even affordable, modest fees for university education would attune young minds to job market prospects. It might also reduce incentives for antisocial behaviour like ragging and unjustified student protests.

Finally, the cost of a bloated public sector—accounting for 14.4% of employment6—receives scant mention in the World Bank report. The public sector has historically been the employer of choice for the average graduate, due to lifetime employment and a pension. But fiscal constraints linked to a high debt to GDP ratio of about 77%7 means that this is increasingly unsustainable. The New Zealand example of trimming the public sector may be instructive—reforms there included a combination of a national public-sector employment audit, natural departures due to early retirement, a redundancy/retraining scheme, increased lateral entry from outside, and introducing new technologies. Salaries were also raised for remaining civil servants that provided incentives for improved productivity and service delivery. Whatever reform is possible within current political circumstance, it should be gradually implemented over a decade.

Decades of providing free education and health care, along with food subsidies, gave Sri Lanka a reputation for being a success story among developing countries in providing basic needs—with an ample supply of cheap, literate, and productive labour. This helped to attract export-oriented foreign investment to the clothing industry and created about 900,000 jobs8 after the country opened up in 1977. But the reputation of Sri Lankan labour may be at risk following a 30-year civil war, alternative spending priorities, and growing institutional imperfections. Combining private sector action with labour market reforms can help put Sri Lanka firmly on the road to upper-middle income status.

[Dr. Ganeshan Wignaraja is Chair of the Global Economy Programme at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies (LKI). The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and not the institutional views of LKI, and do not necessarily reflect the position of any other institution or individual with which the author is affiliated.]

Footnotes

1 World Bank. (2018). More and Better Jobs for an Upper Middle-Income Country. Sri Lanka Development Update. [online]Available at https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/29927

2 EconomyNext. (2018). Sri Lanka GDP grows 3.2-percent in 2018 first quarter. [online] Available at: http://economynext.com/Sri_Lanka_GDP_grows_3.2_perent_in_2018_first_quarter-3-10953.html

3 Central Bank of Sri Lanka. (2018). Unemployment Rate | Central Bank of Sri Lanka. [online] Available at: https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/en/economic-and-statistical-charts/unemployment-rate-chart

4 UNDP. (2018). Empowering women is key to building a future we want. [online] Available at:http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/presscenter/articles/2012/09/27/empowering-women-is-key-to-building-a-future-we-want-nobel-laureate-says.html

5 University Grants Commission Sri Lanka (2017). Sri Lanka University Statistics 2016. [online] Available at:http://www.ugc.ac.lk/en/home/54-statistics/1905-sri-lanka-university-statistics-2016.html

6 Central Bank. (2018). Central Bank Annual Report 2017. [online] Available at: https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/sites/default/files/cbslweb_documents/publications/annual_report/2017/en/14_Appendix.pdf#page=49

7 Central Bank. (2018). Central Bank Annual Report 2017. [online] Available at: https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/sites/default/files/cbslweb_documents/publications/annual_report/2017/en/14_Appendix.pdf#page=7

8 Madurawala, S. (2017). Talking Economics - The Dwindling Stitching Hands: Labour Shortages in the Apparel Industry in Sri Lanka. [online] Ips.lk. Available at: http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/2017/04/03/the-dwindling-stitching-hands-labour-shortages-in-the-apparel-industry-in-sri-lanka/