Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Monday, 22 January 2018 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The nominal market in which workers find paying work, employers find willing workers, and wage rates are determined is defined as the labour market. Labour market outcomes result from a combination of the demand for labour by firms and the labour that workers supply. Firms are the focus of trying to understand labour demand, whilst workers are the focus of trying to understand labour supply. Holistic understanding of the current supply and demand for skills is required to analyse how the two interact and to inform policies to support an inclusive economic growth path. With the ever-changing labour market and economy, timely and relevant labour market information is critical for decision making. It is also essential for career development, locating employment opportunities and sourcing skilled workers. Such information should also guide educational and training programmes to suit the demands of the labour market, and more importantly to influence such demands for the benefit of the country.

Labour Supply

The working age population, labour force, economically active population, economically inactive population, potential labour force, employment, underemployment, main and second job, unemployment, et cetera, are key determinants of labour supply. Information on these aspects has been compiled by the Department of Census and Statistics (DCS) on a quarterly and annual basis since 1990 through the Sri Lanka Labour Force Survey (SLFS). The SLFS provides detailed information on characteristics of the labour force such as age sex and education qualification. This information is necessary to understand the supply side of the labour market which is essential to fully understand the labour market situation in the country. However, there has been a lack of information on the demand side of the labour market. Therefore, the DCS conducted its first ever Enterprise Labour Demand Survey (ELDS) in July 2017 and a report containing the key findings of the ELDS was released recently.

Enterprise Labour Demand Survey

The need for conducting ELDS 2017 was driven by recognition of the importance of ensuring adequate and reliable information on the fit between the skills and competencies of the workforce and the requirements of employers. There was also the concern of a mismatch between the availability of and the demand for skills. This can negatively impact the level of employment and productivity in the workplace.

Specifically, the objective of the ELDS was to gather more information from businesses about their workforce, nature of their business, recruitment patterns, vacancies, hard-to-fill positions, and training for employees. The ELDS 2017 includes a detailed disaggregation by occupations, hiring patterns, difficult-to-find skills, and some comparisons of first-time job seekers with different educational backgrounds. Disaggregation of occupation in labour market data in a standardised manner is essential in the analysis of labour market data. Therefore, the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-2008) was used to classify occupations in this survey.

Survey Methodology

According to the findings of the Economic Census 2013/14, there are little over one million private sector economic units in the country. Among those, there are 189,000 economic units with more than three employees. The ELDS 2017 was carried out as a survey of 3500 enterprises from across the country. The sample was selected using a stratified random sampling technique, to ensure that all categories of enterprises are included in the sample and that it is nationally representative. A structured questionnaire was used to gather and record the data from the enterprises.

Information gathered

Information gathered in this survey was of three types: characteristics of the current stock of employment, labour demand or unfilled vacancies, and the number to be recruited within the next twelve months. This information was collected (a) to ascertain the distribution of workers by key demographics, educational attainment, occupation, skill type, and work experience, (b) to examine the unfiled vacancies by type of occupation, sector etc. in order to identify employment opportunities in the private enterprises, and (c) to ascertain the extent to which employers experience difficulty in recruiting appropriate staff to fill vacancies. Information gathered on recruitment drive during the next twelve months provide an opportunity, not only to identify employment opportunities in the short-term, but also to adjust educational and training programs offered by different institutions.

Employment by sector and age group

The estimated total number of employees in the private sector is approximately five million. The leading categories are service and sales workers (28.8%); elementary occupations (16.9%); plant and machine operators and assemblers (14.6%); and clerical support workers (10.5%). These are skilled or semi-skilled worker categories. Shares reported for managers, professionals and associated professionals were smaller: 7.8%, 8.6%, and 6.2% respectively.

The vast majority (59.3%) of employed persons in the private sector are in the age group of 25-45 years, followed by less than 25 years (21.2%) and 45-60 years  (17.8%). Nearly 2% of current employees in private sector enterprises are past the retirement age of 60 years.

(17.8%). Nearly 2% of current employees in private sector enterprises are past the retirement age of 60 years.

Preparedness of first-time job seekers

The employers were asked to report the job-preparedness of first-time job seekers, in terms of vocational and educational backgrounds, as first-time job seekers varied in this regard. The highest ‘above-average’ preparedness was reported for the first-time job seekers having university degrees with vocational training (94.7%), and the lowest reported for those having only technical and vocational training (60.4%). The percentages vary from 67% to 81% for those having only secondary education, university degree, secondary education or vocational training qualifications.

Problems of labour resources

Enterprises experience difficulties in filling vacancies due to lack of applicants and dissatisfaction of job-seekers with the offered salary. A brief analysis on unfilled vacancies, known as labour demand is presented below. Analysis has been carried by sector, province, occupation, difficult-to-fill vacancies etc.

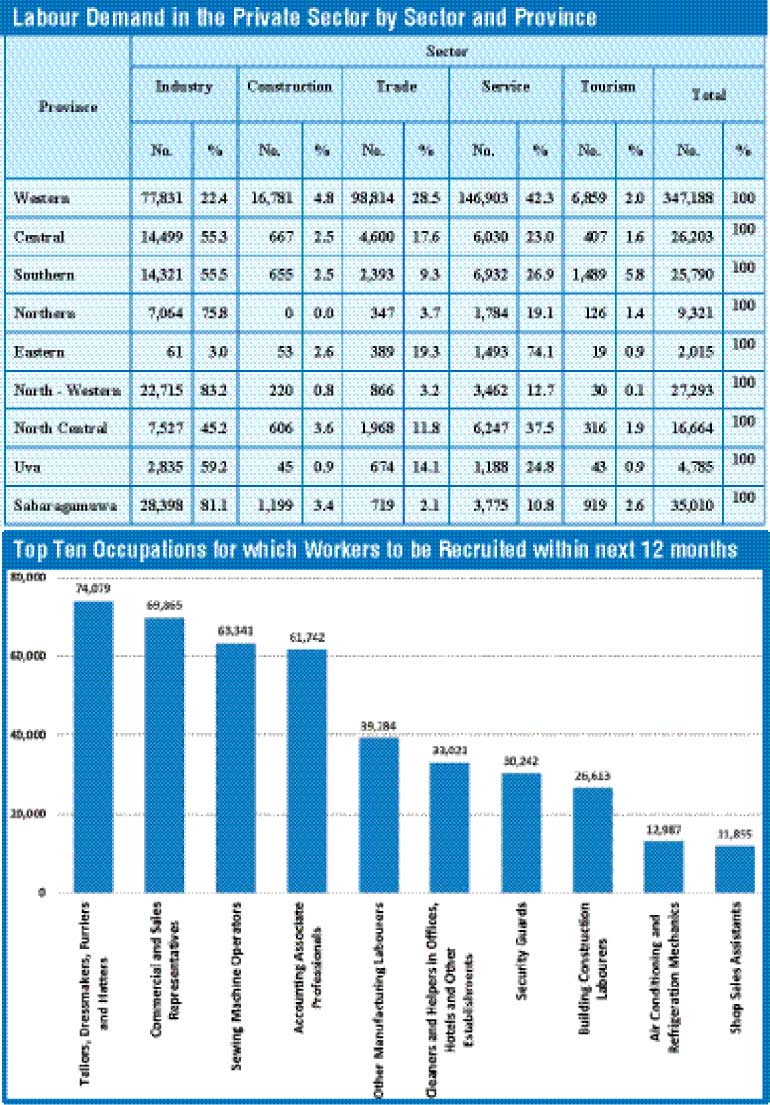

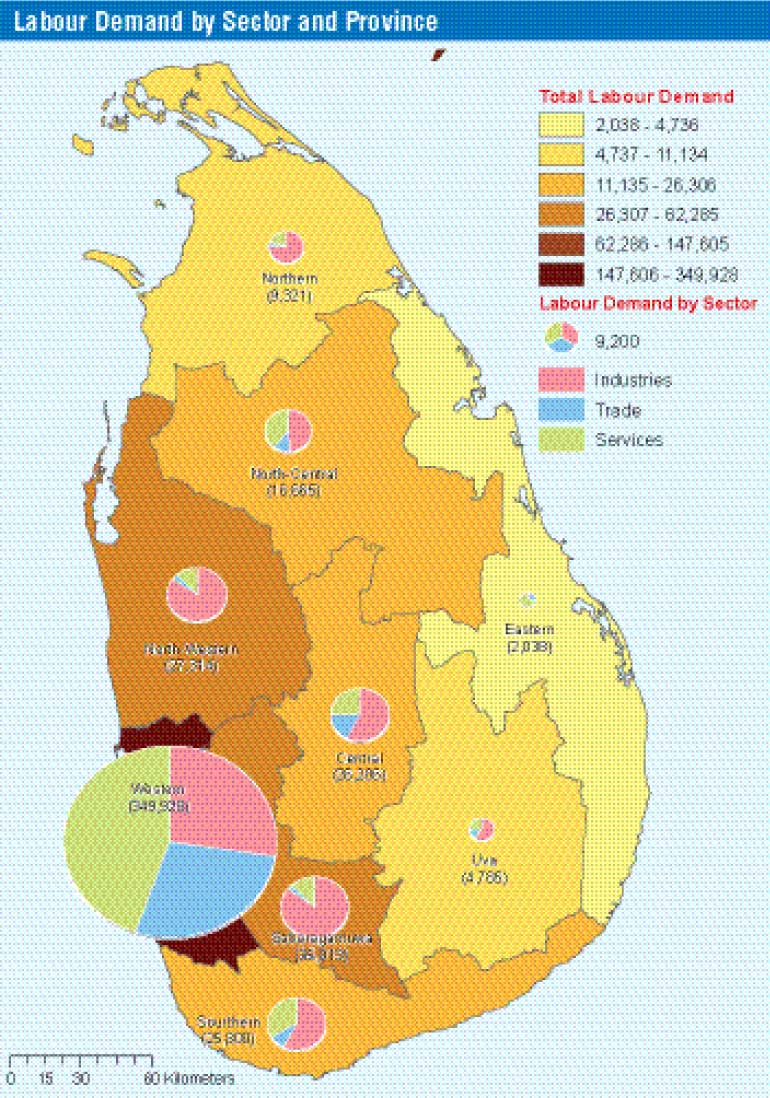

Enterprises were asked to report the vacancies they were unable to fill. The estimated labour demand was 497,300. The service sector reported the highest demand (177,813), followed by the industry sector (175,250) and the trade sector (110,770). Labour demand reported for construction, tourism and agriculture (plantation) sector was 21,000, 20,224, 10,207, and 3,033 respectively.

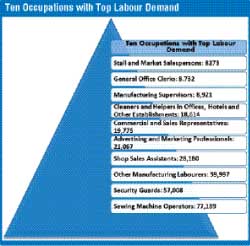

The top five shortages were reported for: sewing machine operators, security guards, other manufacturing labourers, shop sales assistants and advertising and marketing professionals. Reported demand for these occupations was approximately 77,200, 57,000, 39,400, 28,200 and 21,000 respectively.

The labour demand varies very widely across provinces. Of the 497,302 unfilled vacancies the giants’ share (70%) was in the Western province with the smallest share being in the Eastern province (0.4%). Labour demand in different sectors also varies considerably across provinces. For example, the labour demand in the industry sector varies widely from 3% in the Eastern Province to 83.2% in the North-Western province.

Labour demand by sector

Labour demand in the plantation sector was mainly for tea pluckers (2,474), followed by rubber tappers (437). The demand reported for all other occupations of this sector was less than 25.

The total labour demand in the industry sector was 175,250. The majority of over 134,321 were in the formal sector and it was mainly for sewing machine operators (59,659). The same occupation had the highest demand (13,858) in the informal industries sector as well.

In the construction sector, the total demand was 20,000, almost all of it (18,000) in the formal sector. The highest demand was for building construction labourers (4,300), other manufacturing labourers (4,200), and heavy truck and lorry drivers (1000). For all other occupations, the demand was less than 900. In the informal construction sector, the highest demand was for Building construction labourers (671) and masons (647) and it was less than 380 for all other occupations.

Shop sales assistants (22,255) and advertising and marketing professionals (20,744) had the highest labour demand in the trade sector. Shop sales assistants (4,143) were most in demand in the informal trade sector as well, followed by waiters (1,730).

The service sector has been expanding widely in the economy of Sri Lanka, reporting the highest labour demand. The three occupations that reported highest demand were security guards (56,674), commercial and sales representatives (14,360) and cleaners and helpers in office, hotels and other establishments (13,712). In the informal service sector, the highest demand was for hairdressers (4,182).

Difficult-to-fill vacancies

The survey attempted to find out the occupations for which the employers found it difficult to fill. The reported top four difficult-to-fill occupations in the formal sector were sewing machine operators, security guards and other manufacturing labourers. The number of vacancies which they were unable to fill numbered 46,576, 45,316, 31,277 and 17,568 respectively. In the informal sector, the top four difficult-to-fill occupations were sewing machine operators, other manufacturing labourers, creative and presenting artists and carpenters and joiners. Numbers reported were 14,667, 7,800, 3,347 and 3,229 respectively.

Difficulties in filling vacancies

When asked why they could not fill the vacancies, one-fourth of surveyed enterprises reported that people were not willing to do the jobs offered to them, while a little more than one-fifth reported competition from other employers as a reason. Other reasons given were ‘salaries/payments demanded for this occupation are too high’, ‘low number of applicants qualified for the job’, ‘poor terms and conditions (e.g. pay) offered for post’, ‘job entails shift work / unsociable hours’, ‘remote location / poor transport’, ‘seasonal or time limited work’ and ‘other’, with the percentage of employers who selected those reasons were 13.5%, 13.5%, 9.5%, 5.2%, 5.1%, 3.4% and 3.7% respectively.

Plans for hiring workers

Another important area investigated in this survey was the planned recruitment drive during the next 12 months by the employers. In the formal sector, the highest number of workers to be recruited (74,079) was for the occupation of tailors, dress makers and hatters. Following this was commercial and sales representatives and the expected number was 69,865. In the informal sector, the highest number to be recruited (22,400) was reported for building construction labourers.

Skills improvements

In this survey, information was also gathered from the employers on what skills of their workers needed to be improved. Almost 40% of the employers identified team work as the skill that most needed to be improved. Oral communication came second (30%) followed by taking initiative (26%), and literacy (20%). Advanced IT application, management responsibilities and taking leadership was mentioned by 9% - 10% of the employers.

Conclusion

A key finding of this survey is that there is a labour demand of nearly half a million in the private sector institutions having more than three employees. However, the Sri Lanka Labour Force Survey, 2016 has shown that there is a potential labour force of 210,480 who are not actively seeking employment but ready to work given the opportunity. There is also an unemployed population of 363,000. Thus, there are over half a million people who can be employed. However, to do so they need to be provided with knowledge, skills and opportunities as identified by the employers in the ELDS reported above. By doing so, enterprises may obtain the human resources they need. Equally importantly, half a million people who are not productively engaged may be given employment. Appropriate action to bridge the disconnect between the supply and demand in the labour market can have major economic and social benefits directly affecting half a million people, and a large number of enterprises.

The report on the “Enterprise Labour Demand Survey of Sri Lanka” recently released by the DCS is an important resource to inform the planning and provisioning of vocational and training, as well as to assist individuals to make appropriate career and educational choices. The report is expected to contribute to the improvement of the responsiveness of the post-school education and training system to the needs of the economy and society more broadly, by supporting decision-making on matters pertaining to skills planning.

(The writer is Director General – Department of Census and Statistics.)