Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Monday, 16 September 2019 00:40 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Disruptive technology

Technology has always been disruptive. When a new technology is introduced, it changes the way the humankind lives, behaves, earns, interacts and communicates. Some 10,000 years ago, when agriculture and animal breeding were domesticated through the technology available at that time, Homo sapiens stopped moving from place to place on a daily basis for hunting animals and gathering other eatables.

About 200 years ago, the invention of steam power helped mankind to mechanise both agriculture and industry. It reduced the labour input, added another input to production process called physical capital and facilitated Homo sapiens to work on improving their brain power. This was followed by the commercial use of electricity and innovation of assembly line for producing mass consumption goods some 100 years ago. Some 50 years ago, this was revolutionised by the use of new information and communication technology or ICT for production, distribution and consumption.

Industry 4.0

Now, the world has moved to another era in which a new industrial revolution is taking place on the basis of the continuing ICT revolution. This is termed the Fourth Industrial Revolution, also known as 4IR or Industry 4.0 and credit goes to the convenor of Davos based World Economic Forum, Klaus Schwab who coined it in a book published under the same title in 2015. Industry 4.0 deals with the changes in the global economy in terms of artificial intelligence or AI, machine learning, automation and robotisation. All these are digital technologies and therefore, there are three core areas of digital developments that have contributed to usher 4IR. They are the digitisation of value chains, product and service offerings and business models and accessing customers.

Digital divide on top of income divide

Globally, developed nations have moved to 4IR in a significant way. Since the emerging and developing nations have been laggards in this race, there is a clear digital divide between nations in the world on top of the income divide that has been there for some time.

4IR will become a real disruptive technology since it is expected to change the global production system completely. Having realised this threat, some of the emerging nations like Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines, Brazil and Mexico have already prepared roadmaps to get them attuned to it. Sri Lanka is yet to come up with a viable strategy and an effective roadmap to get on to the bandwagon of the fourth industrial revolution.

Singapore, the nation of proactive strategies

It seems that Sri Lanka is waiting, like other backward countries, till the problem would hit it and then take some reactive measures. But good economic management requires the country to be proactive in this game if it is to be a winner. For instance, in 1999, there was no mention of the onset of 4IR. But, Singapore had correctly judged that the future world will be driven by new technologies and it should be an active partner of that disruptive world. Hence, it got its higher learning institutions and universities to concentrate on four areas – the emerging technologies at that time, namely, genetic research, ICT including AI and robotisation, nanotechnology and digitised entertainment – with support from best of the best US universities. New technologies have been added to this list since then, but after mastering the above four, it will simply be a topping up exercise for Singapore to catch up with global developments.

Disruption to Sri Lanka’s apparel industry

In this context, the imminent disruption to Sri Lanka’s apparel industry due to technological advancements and changes in the global markets is a case in point. Textiles and apparels were a new industry that got rooted in Sri Lanka’s economy after 1978 when it went for an open economy policy system. Prior to that, Sri Lanka had both these industries as import substitution industries catering only to the local market.

Apparels were the saviours of Sri Lanka

Apparels being a labour intensive industry began to suffer due to the increases in the manufacturing wages in the Western world around late 1960s. It prompted manufacturers in these countries to locate manufacturing plants in developing countries where quickly trainable cheap labour was abundantly available. This process was known as ‘off-shoring’ or locating manufacturing facilities off to the shores of the mother countries.

Sri Lanka got a new apparel industry on its shores due to its cheap labour plus the textile quota under the previously ruled Multi Fibre Agreement or MFA. The results were dramatic and over the next two decades, its industrial sector could easily beat the hitherto leader in export earnings – the traditional plantation sector consisting of tea, rubber and coconut – to the second place. In the new industrial sector, the textiles and garments grew in export earnings as well as in value addition to the total GDP of the country.

Today, it brings in about $ 5.5 billion of export earnings amounting to nearly a half of total such earnings. It also contributes 17% to industrial value addition and 5% to the country’s total GDP. Nearly a half of the industrial direct employment is also generated by this sector.

Game changer in apparels

But all this is going to be changed in the future. In the near to short-run, the apparels will shift from Sri Lanka to newcomers like Bangladesh, Myanmar, Vietnam and some of the East African countries due to two reasons. One is the rising wages in Sri Lanka compared to its competitor countries. The other is the loss of preferential treatment to Sri Lanka’s garments by EU’s GSP + due to the country moving to an upper middle income country. This latter factor which is expected to become operative as from 2023 will compel Sri Lanka to compete with other countries by improving its productivity rather than relying on tariff concessions. In the medium to long run, Sri Lanka’s apparel sector is going to be disrupted by changes in market preferences and enabling technological developments.

Apparel manufacturing coming home

In a survey report published by McKinsey Research Institute in 2018 under the title ‘Is Apparel Manufacturing Coming Home’, apparel industry is being lured back to major markets in Europe and the UK, on one side, and North America, on the other, due to two facilitating developments.

One is the automation of industry through robotic development and machine learning supported by advancements in AI. The other is the need for keeping the markets supplied within the shortest time possible. The first development has caused the apparel industry to be located in major markets, known as on-shoring or re-shoring. The second has caused the industry to be located in countries close to major markets, a process known as near-shoring.

Sewbots and Cobots taking over production

It seems that Sri Lanka is waiting, like other backward countries, till the problem would hit it and then take some reactive measures. But good economic management requires the country to be proactive in this game if it is to be a winner. For instance, in 1999, there was no mention of the onset of 4IR. But, Singapore had correctly judged that the future world will be driven by new technologies and it should be an active partner of that disruptive world. Hence, it got its higher learning institutions and universities to concentrate on four areas – the emerging technologies at that time, namely, genetic research, ICT including AI and robotisation, nanotechnology and digitised entertainment – with support from best of the best US universities. New technologies have been added to this list since then, but after mastering the above four, it will simply be a topping up exercise for Singapore to catch up with global developments.

Under re-shoring, the industry is now being relocated in the UK, Portugal and USA. Under near-shoring, it is being shifted to Turkey, Macedonia, Tunisia and Morocco to supply the European markets and to Haiti, Honduras, El Salvador, Mexico and Guatemala to supply the North American markets. Both these relocations are to be supported by sewing robots or Sewbots and collaborative robots or Cobots.

According to McKinsey, by 2025, about 74% of the North American markets and about 61% of the European markets will be supplied by both re-shoring and near-shoring manufacturing outlets. The re-shoring activity is being done by European countries in an accelerated phase. A report published by European Foundation or EuroFound in 2019 under the title ‘Future of Manufacturing in Europe’ has tracked that between 2014-18, more than 210 new production facilities have been re-shored in Europe. Of them, 44 had been re-shored in the UK, followed by 39 in Italy and 36 in France. Since about 92% of Sri Lanka’s apparels goes to EU, USA and Canada, this emerging development is absolutely disruptive to Sri Lanka.

Unbundling is the solution

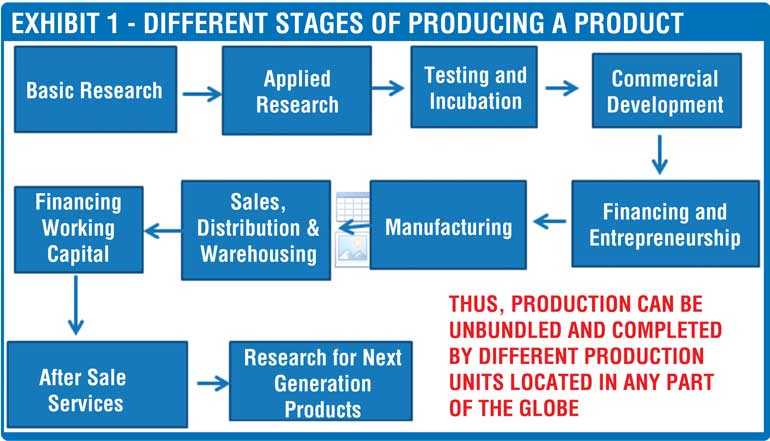

In this dreadfully threatening situation, Sri Lanka should necessarily have a proactive strategy to take it seamlessly to the next stage of global development. In the present global production model, a country does not seek to produce a whole product within a single manufacturing facility. Instead, they produce different components which will finally be assembled into a whole product at an assembling facility. This process has been facilitated by the separation of a production process into different stages as given in Exhibit 1. It has helped manufacturers to unbundle production and assign it to numerous production facilities located throughout the globe.

Global production sharing networks

Since the components come from many countries, a product today is shared by the global community rather than a single country. This is known as ‘global production sharing model’. Tony Hines has documented in his 2004 book ‘Supply Chain Strategies’ that though Ford Escort car is being finally assembled in the UK, the components for the car had come from 14 different countries. Hence, adding ‘Made in England’ tag to that car is a misnomer.

Similarly, parts for iPhone 6 had come from 785 different factories in 31 countries, though it is finally assembled in Foxconn factory located in China. Another emerging development is Ceylon tea. Sri Lanka exports orthodox black tea in bulk form, tag-lined Ceylon Tea, to Dubai and Vietnam. In those two destinations, Ceylon tea is blended with other teas coming from India, Malaysia, Indonesia, tea producing East African countries, converted to value-added products and supplied to the market.

Sri Lanka’s entry to the new production model

Two Sri Lankan manufacturing outlets have joined the global production sharing networks in a big way. One is the Lanka Harness which supplies sensors for the activation of life protecting airbags in motor vehicles. How this industry came into being was covered in an article in this series published previously (Available at: http://www.ft.lk/columns/Rohan-Pallewatta-Man-who-has-proved-that-Sri-Lanka-can-also-do/4-654568). The other is MAS Holding’s arrangement with Nike, sports shoe manufacturer, to supply the canvas for its running shoes and materials for sportswear through a production facility called MAS Matrix located in its Fabric Hub in Thulhiriya.

MAS Group strategy: Stay ahead of competitors through innovation

Deshamanya Dr. Mahesh Amalean, one of the co-founders of MAS Holdings, in delivering Professor Uditha Liyanage Memorial Oration in Colombo recently, narrated how the group was created with a strong value system based principally on trust. He revealed that, in the formative years, there had been occasions where multi-million dollar partnerships had been operated smoothly by the group with foreign collaborators, without being interrupted even by a hiccup, purely on verbal agreements.

The current thrust of the MAS Group, according to Amalean, has been to adopt strategies to stay ahead of competitors by continuously renewing strategies and investing in the future. It wants to be identified ‘synonymous with innovation’ and has therefore, created a robust ecosystem – an interlinked, interacting and interdependent network – within the group to foster innovation. That innovation may come from its own research arms and from technologically more advanced partners out there. Its partnership with Nike has been in line with this strategy.

Using yarn made of recycled PET

“We started our Nike partnership on a very modest scale with just 8 machines and 8 people in 2012,” Chaminda Mirando, Operational General Manager of MAS Matrix, explained to me and a group of students from the University of Sri Jayewardenepura who visited the factory recently. “We got the technology for manufacturing the upper canvas of Nike’s sports shoes. The basic raw material is the yarn manufactured from recycled polyethylene terephthalate, commonly known as PET. We got the award for recycling 1 million PET bottles last year. But the current local supply is sufficient to meet only about a fifth of our requirements. Hence, the balance is being imported from China,” he said.

Graduation from 8 to 1,600 machines

At present, MAS Matrix is equipped with some 1,600 machines which are fully automated and it employs about 3,200 young talents. Floor workers who are provided with free meals and free transportation are also paid a decent salary going by the standards of the industry. “Our production is unique in the sense that it has zero waste landfill strategy,” its floor manager Rangana Guruge explained to us. “What it means is that we further recycle defect items and cut-pieces. Over our roof, we’ve installed solar panels that supplies about 1 megawatt of electricity to CEB per annum. But that’s about 10% of our energy requirement. We, therefore subscribe to green manufacturing,” he elaborated.

Carbon footprint should be measured from end to end

Of course, attempt by MAS Matrix to adopt green manufacturing is laudable. However, to earn the full green certificate, a manufacturer should ensure green technology from one end of the production to the other. In the case of apparels, it should start from raw materials, continue through manufacturing, distribution, wholesaling and retailing, using and finally disposing. The reduction of carbon footprint should be attempted at all these stages. A path-finding study by Nobel Laureate Mohan Munasinghe and others on the carbon footprint of garment manufacturing in Sri Lanka has revealed that a common brassiere causes end to end carbon emission equal to the driving of a passenger car by 3.4 miles (Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287406614_Supplyvalue_chain_analysis_of_carbon_and_energy_footprint_of_garment_manufacturing_in_Sri_Lanka).

Expansion of product range

“In addition to manufacturing top canvas of sports shoes, we also produce two other items for Nike,” Mirando told us. “One is the sports bra for women, known as FlyKnit bra. It is a joint creation of both MAS Matrix and Nike research teams. The other is a pneumatic active compression wrap that improves blood circulation and helps relieve muscle aches due to athletic performance. This product is called SPRYING and it’s a unique creation of our research teams.”

Taking into account the emerging developments in the apparel sector, MAS group has also moved out. It has set up factories in USA by way of re-shoring factories and in Honduras, Haiti and El Salvador as near-shoring factories. In addition, design centres have been set up in USA, UK and Italy. Thus, MAS Group has taken Sri Lanka to the global production sharing network effectively.

MAS Group and Lanka Harness have undoubtedly shown the way forward strategy which Sri Lanka should follow. But, for Sri Lanka to prosper and become a wealthy nation, it should have a critical pool – a sufficient number that can influence its behaviour – of new innovative entrepreneurs. Proactive action should be taken as a top priority to deliver this critical pool to the nation.

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)