Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Wednesday, 10 February 2021 00:25 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

As Sri Lanka celebrated the 73rd Independence anniversary with much pride, her economic status has remained unimpressive in many fronts for decades, in spite of the initial social progress that was achieved in terms of health, education and social welfare, far ahead of many developing countries. The policies adopted by the successive governments since independence have had much do with this economic plight.

As Sri Lanka celebrated the 73rd Independence anniversary with much pride, her economic status has remained unimpressive in many fronts for decades, in spite of the initial social progress that was achieved in terms of health, education and social welfare, far ahead of many developing countries. The policies adopted by the successive governments since independence have had much do with this economic plight.

Economic hardships from COVID-19 pandemic

The country’s longstanding economic fallout is compounded now by the COVID-19 pandemic which has afflicted the entire globe. There are signs of inflation knocking at the door. The impending inflation will not only worsen the living standards of the people, but also severely restrain the post-pandemic economic recovery.

The underlying inflationary pressures emanate from demand-side factors such as the budget deficit and monetary expansion, coupled with supply-side effects including domestic production setbacks, import restrictions and rupee depreciation.

Price controls have good intentions but ineffective

The poor who have lost their means of living due to the pandemic are the worse affected by the price hikes of essential consumer goods.

In order to overcome their hardships, the Government has introduced a series of price controls on essential consumer goods on several occasions in recent weeks. Although such measures have been implemented with good intentions, their success will largely depend, inter alia, on the capacity of the authorities to ensure that the market prices do not exceed the gazette price ceilings. Historical evidence proves that such administered measures are not viable, particularly in a free market economy.

CCPI shows low inflation

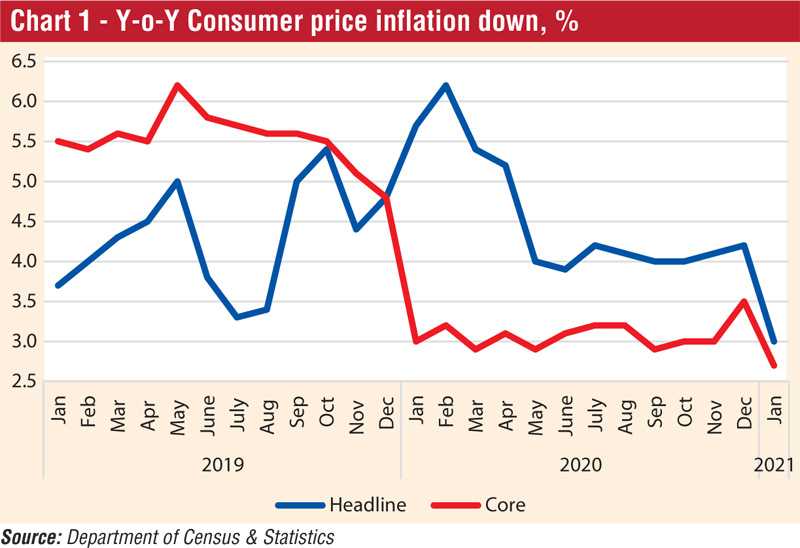

The Colombo Consumer Price Index compiled by the Department of Census and Statistics (DCS), which is frequently used for policymaking purposes, shows that inflation is decelerating (Chart 1). Accordingly, the headline inflation was down to 3.0% in January 2021 from 5.7% a year ago, and the core inflation (excluding food, energy and transport) declined to 2.7% in January this year from 3.0% a year ago.

Rise in food prices

Although the CCPI indicates lowering of inflation, rapid price increases of certain essential consumer goods, particularly those of food items, are evident in recent months. For instance, the average price of Samba rice went up by 15% to Rs. 116.83 last month from 101.72 a year ago, according to DCS’s own data.

The price of Nadu rice has risen by as much as 18% to Rs. 115.00 from last year’s price of Rs. 97.15. The difference between the price of these two varieties seems to be too low as the price of Samba rice is usually higher than the other variety in the market.

Problematic CCPI does not gauge inflationary pressures

The accuracy of any consumer price index depends on the weights assigned to different commodities in the consumer basket used for compiling the index and data collection methods.

The weights given to certain commodities in the consumer basket of the CCPI seems to be problematic. For example, the weight given to rice, which is the country’s staple food, in the basket is as low as 2.94% whereas relatively higher weights of 1.47% are given for chicken and 2.16% for milk powder. Even within the rice varieties, Samba rice carries a higher weight of 1.47%, in comparison with a weight of only 0.46% for Nadu rice, which is widely used by low-income households.

Considering such drawbacks, it is doubtful whether the CCPI, which is used as the main inflation indicator for policy purposes, reflects the underlying inflationary pressures ignited by high money growth and supply-side shocks in the backdrop of COVID-19 pandemic.

No consumer price index is perfect, and therefore, it is desirable to look at alternative inflation indicators rather than blindly using a single indicator, as discussed below.

Producer prices going up

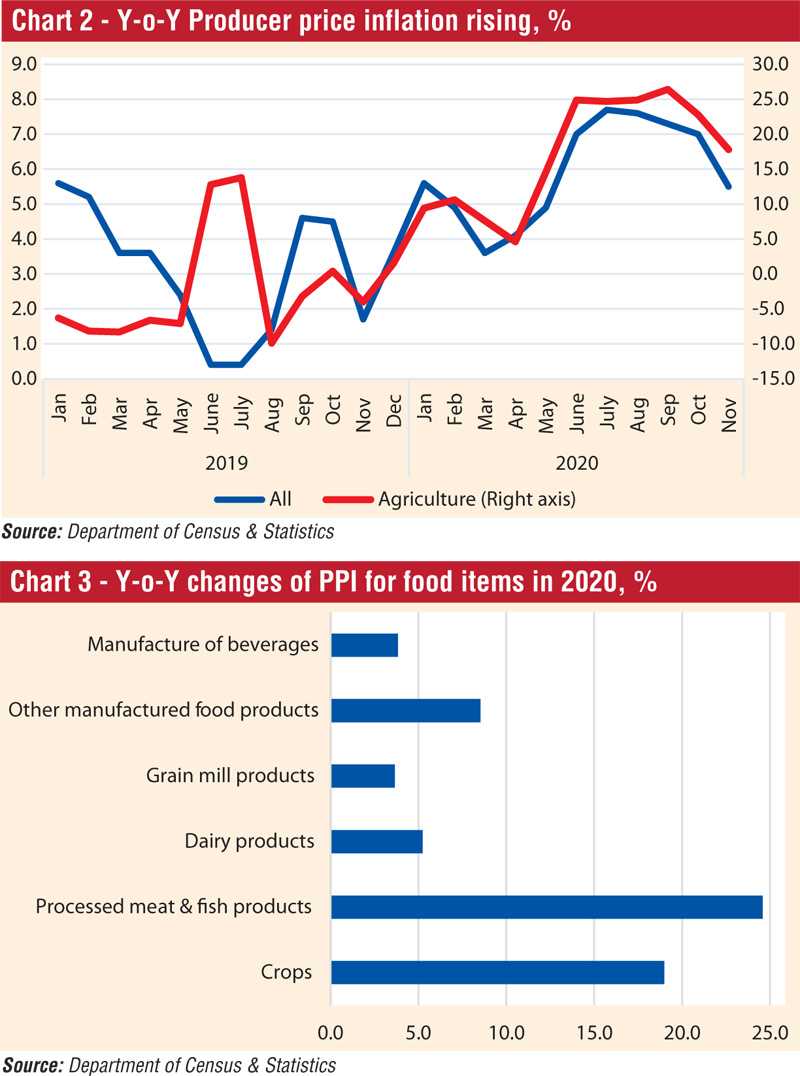

A complementary indicator that can be used is the Producer Price Index (PPI), which is also computed by DCS. It measures what is known as farmgate prices or the average prices received by domestic producers of goods and services. PPI gives an indication of the underlying trends of consumer prices.

The PPI rose by 5.5% Y-o-Y in November 2019 as against 1.7% a year ago (Chart 2). The PPI for the sub-group of agriculture for agriculture which is the major source of country’s food supply, rose by as much as 17.8% Y-o-Y in November last year as against minus 4.0% a year ago.

Producer prices for crop products, fish and meat and processed food recorded substantial increases in 2020 (Chart 3).

Such price increases are not reflected in CCPI, and hence, PPI seems to represent inflationary trends more realistically.

Demand-pull effects

The rapid increase in bank credit to the Government and State-Owned Enterprises led to raise the money supply by as much as 23.4% in 2020, compared with 7.0% in 2019. Money supply as a ratio of GDP, which reflects market liquidity, rose from 46% in 2019 to around 54% in 2020. It is likely to be as much as 63% of GDP this year, according to my projections.

However, bank credit to the private sector is picking up at slow pace, as elaborated in my article in Daily FT (http://www.ft.lk/columns/Bank-credit-to-private-sector-picking-up-at-slow-pace-in-response-to-monetary-easing/4-712502).

The monetary expansion has resulted in excess liquidity in the market pressurizing aggregate demand. In the backdrop of supply shortages due to the pandemic, such excess demand is bound to accelerate inflation soon.

These adverse trends clearly show the imminent danger in adopting the so-called Modern Monetary Theory-styled policy by the Central Bank to finance the government debt by printing money, as I argued out in a previous FT column (http://www.ft.lk/columns/Money-printing-to-repay-Govt-debt-worshipping-MMT-is-likely-to-magnify-economic-instability/4-710612).

Cost-push effects

The ongoing depreciation of the rupee is a major factor pushing up inflation from the cost side. With the rupee depreciation, imports are getting costlier and as a result, the prices of consumer goods which form a significant portion of the consumer basket will continue to rise thus, accelerating inflation.

Apart from such direct effects of currency depreciation, further rounds of money growth are going to take place as a consequence of possible increases in the budget deficit due to exchange rate depreciation-led government expenditure hikes. Meanwhile, workers in certain sectors are already agitating for wage hikes to compensate for inflation.

There are also indications of an upward revision of the country’s fuel prices soon due to fuel price increases in international commodity markets. Such price increase will have spill-over cost effects on the entire economy causing enormous inflationary pressures in all sectors.

Higher inflation calls for further rupee depreciation to sustain the real exchange rate at realistic levels so as to ensure balance of payments equilibrium. Eventually, it has already become a vicious circle of rupee depreciation, inflation, budget deficit, money growth, wage increases and so on.

Savers are losers

In the backdrop of annual inflation running over 5%, a three-month Treasury bill which has an ongoing yield rate of 4.7% per year gives a negative real of interest rate (nominal interest rate minus inflation) to investors. Savings and fixed deposits of banks and other financial institutions also remained around such low level. Thus, savers are the losers in the present low interest rate episode.

As a result, a large number of low and middle-income households who solely depend on fixed deposit earnings are badly hit by low interest rates.

Meanwhile, the affluent investors tend to shift to alternative instruments including company shares, real estates and various risky speculative deals.

Bullish stock market driven by excess liquidity

The Colombo Stock Exchange (CSE) gained momentum during the last two of weeks supposedly becoming the world’s best performing bourse. The bullish market has been entirely driven by local investors while foreign investors exiting the market.

The buying spree of local investors is largely a reflection of the excess liquidity in the economy prompted by the monetary easing policy measures adopted by the Central Bank since last year to recover the economy from the fallout caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Such unusual asset price hikes, which seem to be incompatible with market fundamentals, enable the rich to gain enormous profits even during this pandemic time through trading in the stock market and engaging in various other speculative and illicit dealings while the poor are suffering silently without even having their basic human needs.

The ultimate result is that the poor get poorer while the rich get richer worsening income disparity during these difficult times.

Wakeup call for policymakers

Given the fast money supply growth, rupee depreciation, world fuel price hikes and supply shortages in the backdrop of the pandemic, there are signs of high inflation in the coming months.

The CCPI, which is frequently used as the single most important inflation indicator for policymaking purposes does not seem to reflect such demand and supply-side inflationary pressures accurately. As discussed in this article, therefore, supplementary indices such as PPI might be helpful at policymaking levels. PPI shows an upward movement of inflation in contrast to CCPI.

While it is imperative to adopt expansionary fiscal and monetary policies during this crisis period as practiced in many other countries, precautionary measures need to be taken to counter the impending inflationary tensions.

The recently introduced price controls might be useful in a limited manner to ease inflationary tensions during the pandemic, but concrete economic strategies are essential to deal with the root causes of inflationary pressures, as discussed above. Correction of the disarrayed macroeconomic fundamentals must be an essential component of such strategies.

(Prof. Sirimevan Colombage is Emeritus Professor in Economics at the Open University of Sri Lanka and former Director of Statistics, Central Bank of Sri Lanka.)