Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Wednesday, 16 December 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

How we ended up with an executive presidency in this country is attributable to an idea conceived in the mind of by J.R. Jayewardene, apparently first expressed at a meeting of the Ceylon Association for the Advancement of Science in 1966

“For forms of government let fools contest. Whatever is best administered, is best” – Alexander Pope

With the adoption of the 20th Amendment to the Constitution, the office of the executive president has  once again assumed a decisive role in Sri Lanka’s social and economic excursion. Yes, it is no more than an excursion, a journey ought to have a clear destination.

once again assumed a decisive role in Sri Lanka’s social and economic excursion. Yes, it is no more than an excursion, a journey ought to have a clear destination.

If the 19th Amendment to the Constitution whittled down the powers originally conferred on the President, the amendment which followed immediately after (20th), restored and further strengthened presidential powers.

Constitutional pundits argue that the people gave a mandate for the 19th Amendment and few years later gave a second mandate for the 20th, in effect, two contradictory mandates within a span of about five years. Clearly, when it comes to constitution making, the people on this island are at sixes and sevens!

The preceding four decades have shown that the executive presidency, this controversial creature of the 1978 Constitution, has only further bedevilled the desolate landscape which is Sri Lankan politics. Some time or other, almost every segment of political opinion has damned the executive presidency, its abolishment has figured in nearly every election manifesto in the last 40 years. But once installed in office, the incumbent is less enthusiastic, becoming lukewarm on the idea of diminishment of self; but then, such is the temper of our politics; the person first, the country only a distant second, and election promises can be explained away.

It cannot be said that the office of the executive president was the result of an organic growth of our constitutional evolution; historically, we see no discernible trend towards such a concept; it is neither a product of the political maturity of the people, nor a symbol of their philosophies of good governance. It was not an idea that grew out of pressing necessity, there was no popular clamour for an executive presidency in the country. On the contrary, it is the singularity of the origin that strikes one; an idea conceived solely in the head of one man, eventually to be brought to fruition by himself, after being elected Prime Minister with a whopping majority in 1977; the UNP winning 139 seats in a 168-member Legislature.

J.R. Jayewardene

As with other Sri Lankan politicians, J.R. Jayewardene too did not leave behind an autobiography. Neither do we have any treatise or even essays wherein he expatiates on the relative merits of the hybrid system he proposed. There are a few recorded speeches where Jayewardene expounded the usefulness of a presidential system, as he saw it: but these are only speeches, made to a general  audience, fragmentary and imprecise.

audience, fragmentary and imprecise.

To fill in the blanks, we need to turn to other literature, particularly his biography, ‘J.R. Jayewardene of Sri Lanka’ by K.M. De Silva and Howard Wriggins. By far the best biography of a Sri Lankan politician, the two volume story of J.R. Jayewardene (1906-1989, when he retired from public life) is essential reading for a student of Sri Lankan politics; the hopeful decades before independence and the floundering years since. When an 83-year-old Jayewardene said farewell to public life in 1989, the country was virtually on fire, the LTTE marching defiantly in the north, while in the south the proscribed JVP had unleashed a reign of terror.

J.R. Jayewardene had begun his political life 50 years before, in the last decade of the British Raj. As the pace quickened towards independence in the 1930s, optimism was high: all things were possible, if only we were independent! Nascent capitalism introduced by the colonial powers had planted the seed of “primitive accumulation,” money flowed into the pockets of those who grasped the potential of the system, enriching a few willing families greatly.

Unfamiliar, but much enjoyed wealth, careers and opportunities opened up for them; an education at a missionary school, a new lifestyle, introduction to a much larger world than previously thought of in this small colonial backwater, emboldened the young men and women of these families to aspire to even greater things.

They will lead an independent country, having everything that England had: a parliament, judges, media, universities, industries, the possibilities were endless. J.R. Jayewardene was very much a part of that intoxicating optimism and also the subsequent atrophy; the slow descent from hope and promise to disillusionment, cynicism and degradation.

As observed by Kumari Jayawardena, the eminent academic, our biographers are inclined to eulogise their subject, it matters not the character’s true legacy. De Silva and Wriggins stand in another continent; although sympathetic towards a personality they had associated with for long years, the biography is objective, scholarly and by no means obsequious.

In the selection of his biographers we owe it to J.R. Jayewardene, perhaps his broader culture inclined him in that direction. The duo, K.M. De Silva, Professor of History, and Howard Wriggins, US Ambassador to Sri Lanka (1977-80) who had received his PhD from Yale and a recognised authority on South Asia, took a good 15 years to complete the J.R. Jayewardene biography. Subsequent leaders have preferred abject careerists, eager apprentices and young amanuenses to tell their story; shallow lives written of by callow hands.

The executive presidency

How we ended up with an executive presidency in this country is attributable to an idea conceived in the mind of by J.R. Jayewardene, apparently first expressed at a meeting of the Ceylon Association for the Advancement of Science in 1966:

“The executive is chosen directly by the people and is not dependent on the legislature during the period of its existence, for a specific number of years. Such an executive is a strong executive, seated in power for a fixed number of years, not subject to the whims and fancies of an elected legislature; not afraid to take correct but unpopular decisions because of censure from its parliamentary party. This seems to me a very necessary requirement in a developing country faced with grave problems such as we are faced with today.”

Although Jayewardene was Minister of State and in effect Deputy Prime Minister of the UNP Government (1965-’70), for this out of the blue idea, there was neither support from his party nor encouragement from his leader, Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake.

The idea hibernated to resurface six years later when in 1972 the Coalition Government (United Front) of Sirima Bandaranaike moved to adopt a republican constitution, arguing that a new constitution was a prerequisite for the social and economic regeneration the country desperately needed. J.R.  Jayewardene as Leader of the Opposition moved a resolution in the House of Representatives which then was sitting as a constituent assembly. His 1966 idea, had by that time taken definite shape:

Jayewardene as Leader of the Opposition moved a resolution in the House of Representatives which then was sitting as a constituent assembly. His 1966 idea, had by that time taken definite shape:

“The executive power of the state shall be vested in the president of the republic who shall exercise it in accordance with the provisions of the constitution…”

“The president of the republic shall be elected for seven years for one term only by the direct vote of every citizen over 18 years.”

“The president of the republic shall preside over the council of ministers.”

His resolution seconded by UNP MP R. Premadasa was given short-shrift by Colvin R. De Silva, Minister for Constitutional Affairs, who was presiding over the introduction of the 1972 Republican Constitution. Even the rest of the UNP caucus was unsupportive, the party’s Leader Dudley Senanayake (Senanayake retained party leadership, while Jayewardene led the small UNP parliamentary group, a repeating theme it seems in our ‘big man’ politics) was sceptical, observing:

“A presidential system has worked in the United States, where it was the result of a special historical situation. It worked in France, for similar reasons. But for Sri Lanka it would be disastrous. It would create a tradition of ‘Caesarism’. It would concentrate power in a leader and undermine parliament and the structure of political parties. Generally, it is a system for a Nkrumah or a Nasser, and not for a free democracy.”

J.R. Jayewardene was not to be denied, after gaining a steamroller parliamentary majority at the 1977 General Elections, he held the key (Dudley Senanayake had passed away in April 1973).

A mandate at a general election is one of those bewitching fictions of the democratic process. It is not a standalone, one issue vote. Whether the desperate voters were motivated by their wish to see an end to the tortures of the Sirima Bandaranaike Government (1970-’77), beguiled by the eight kilos of dry rations promised by the UNP, wanted to enter a kingdom of righteousness (‘Dharmista’) which J.R. Jayewardene prophesied, were enamoured of the new presidential system proposed by Jayewardene, or were tempted by all of these allurements or none of them, we will never know.

Our politicians are not inclined to ponder such ethical subtleties, declaring a mandate they went ahead with their presidential system project. Constitution making ought to be a deliberate process, requiring more than a mere working knowledge of the country and its culture, wide consultations are essential, much consideration must be given before formulating the primary law, which will also affirm our values, point to our future. Although lawyers have an important role to play, constitution making is a national effort, multi-disciplinary by its very scope.

Jayewardene was sworn in as Prime Minister on 23 July 1977 (elections were on 21 July); by September he had moved in Parliament an amendment to the then Constitution which was in effect the structure of the new constitution.

The procedure that was followed

A.J. Wilson, the respected legal academician and adviser to Jayewardene, summarised the procedure followed:

“It (the amendment) was only taken up at Cabinet level (it was not presented to the Government parliamentary group before it was placed before the Legislature for debate), duly approved, and in addition certified by the Cabinet as a bill that was ‘urgent in the national interest’. Under this procedure it was sent through the Speaker direct to the Constitutional Court for its verdict. The Court under the existing Constitution had to give its verdict within 24 hours. The Court conformed to the request and did not in any way fault any of the contents of the amending bill. It was then presented to the National State Assembly for debate and approval.”

When Jayewardene introduced the bill for debate in the National State Assembly on 22 September (1977) the procedure followed was unusual, debate on the bill was adjourned for two weeks, ‘to give the public an opportunity to express its views’. Even when possessed of an unassailable majority, subterfuge and manipulation comes as second nature.

Wilson further observes;

“Opposition circles were scornful of the Cabinet’s endorsement of the bill as being ‘urgent’ and then permitting time to intervene between JR’s speech, the discussion by the House and the decision to put off its coming into force until February 1978.”

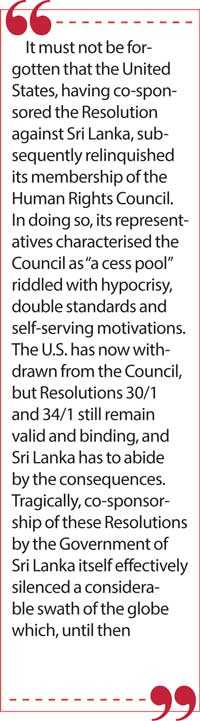

On 20 October 1977 the National State Assembly appointed (through the Speaker) a Select Committee with J.R. Jayewardene as Chairman to consider the revision of the Constitution and other written law as the committee considered necessary. As happened, the Select Committee lacked broad representation, the TULF, the main Opposition (in that skewed Parliament) absorbed in ethno/regional issues refused to participate on the committee. Subsequently, the SLFP, carrying the second most voter base (Sirima Bandaranaike) also withdrew from participation.

Controversial from the beginning

The passage of the executive presidency was not propitious; the office has been controversial from the beginning. Based solely on one person’s concept of effective governance, Jayewardene’s notion that an elected president can act irrespective of Parliamentary support has been proved to be fallacious. Every time the President lacked Parliament support, he/she had become ineffective. Contrary to Jayewardene’s expressed wish to see a president empowered to act independent of the Legislature, in practice, he appears to have limited the scope of the president.

Quite early in his tenure of office as President, JR decided against establishing a powerful Presidential Secretariat. In a letter dated 9 February 1978 to A.J. Wilson who had advised him to establish a powerful secretariat as an essential feature of a presidential system, Jayewardene wrote:

“I must say I am very reluctant to appoint advisers who will be around the President. The reason is that I wish the President to have only his Prime Minister and the Cabinet of Ministers as advisers because they represent the people as Members of Parliament.”

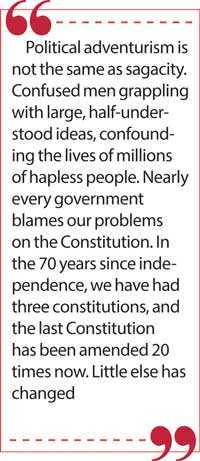

An opinion which runs counter to what he said at the Ceylon Association for the Advancement of Science. Obviously, the ramifications of an executive president had not been fully digested, political adventurism is not the same as sagacity. Confused men grappling with large, half-understood ideas, confounding the lives of millions of hapless people. Nearly every government blames our problems on the Constitution. In the 70 years since independence, we have had three constitutions, and the last Constitution has been amended 20 times now.

Little else has changed.