Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Friday, 30 March 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

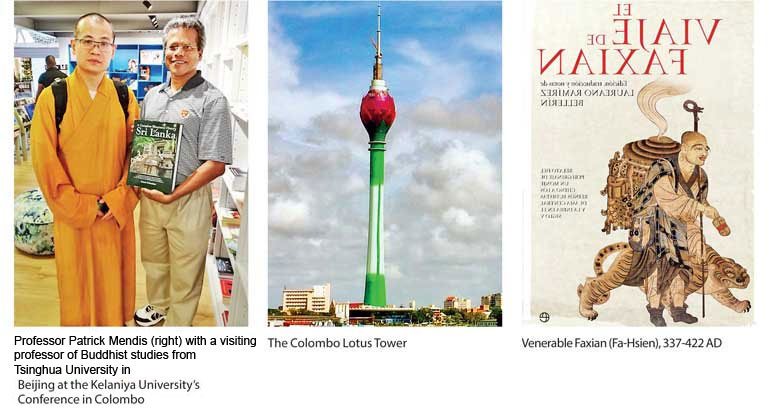

In China’s foreign policy in Asia, Beijing has already rejuvenated the Buddhist diplomacy in Sino-Sri Lankan relations that began in the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD). Over two millennia later, Sri Lanka will soon inaugurate the Chinese-built 350-metre-high Lotus Tower in Colombo, a symbol that manifests the ancient Buddhist peace and diplomatic intercourse between the two nations.

The Buddhist tower, which is seen from predominantly Hindu neighbour India, is a hallmark of China’s geostrategy associated with its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This purpose-driven skyscraper with its sophisticated telecommunications technology is the tallest in South Asia.

The Chinese re-engagement with the Buddhist “Kingdom of the Lion,” as the famous Chinese scholar-monk Faxian (337-422) had called the island in his Records of Buddhist Kingdoms, began the first recorded profile of Sino-Lanka religious foundation. Before arriving in the Anuradhapura Kingdom (377 BC-1017 AD) of Sri Lanka, Faxian travelled across India in search of Buddhist manuscripts. After the reign of Indian Emperor Ashoka the Great (304-232 BC), Buddhism had long departed its birthplace, but Sri Lanka remained the epicentre of Buddhist learning and teaching, attracting pilgrims from China, India, and elsewhere. This enduring Sino-Lankan Buddhist and diplomatic relationship continued—except for the period of European colonialism.

The undercurrent of that long history of civilisational cultures is still pervasive in the mindsets of strategic thinkers. With this legacy, my interests have naturally deepened over the years as the United States, China, and Sri Lanka have triangulated their diplomatic and trade relations. The Sino-Lanka connection has also increasingly drawn American attention, especially after The Kerry-Lugar Report (2009) in the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee where I once worked. Thus, I ventured out to find this ancient history to get a glimpse at a possible future for the United States in the Indo-Pacific region, as past is prologue in Sino-Lanka relations.

Rediscovering roots

Born in Sri Lanka, but later naturalised a US citizen, I developed an intense curiosity about the United States first, and China second. American Peace Corps and 4-H Volunteers visiting my village in the late 1960s had an enduring impact on my childhood views on the United States and its spirited sojourners in freedom. But the teenage years in the 1970s were progressively influenced by China and its ancient connections to Sri Lanka - especially my birthplace of Polonnaruwa, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It was the second capital (1056-1236) of the Buddhist nation after the Anuradhapura Kingdom.

My formative years were filled with the free propaganda literature of the “victorious” Cultural Revolution and its powerful images of industrial and agricultural China, promoted by the Socialist Government (1971-77) of Sirimavo Bandaranaike, the first woman prime minister of the world. I was then a farmer’s son (a Catholic father and a Buddhist mother) adopted by my paternal Catholic grandparents in rice-growing Polonnaruwa, and attended the Sunday mass at the Holy Rosary Church and went to a Buddhist high school. I had the best of both worlds as I developed my affinity for a “Christian America” with political freedom and a “Buddhist China” with economic development.

All that changed when I arrived in Minnesota on an American Field Service (AFS) high school exchange scholarship in 1978.

The latent interest in Sino-Sri Lankan affairs was revived when I became a visiting professor of the University of Maryland in Xian, the ancient capital of China. After my government service in the US Department of State, I began to visit China and travelled to all the provinces and climbed every major Sacred Mountain of Buddhist, Confucian, Daoist heritage that collectively forms the perennial Chinese culture and national identity.

While climbing the Sacred Buddhist Mountain of Mt. Emei, I had a satori (awakening) moment. I suddenly realised the enduring and purpose-driven Sino-Lanka connection, which is at last manifested in the Colombo Lotus Tower—the “crown jewel” of BRI.

Mt. Emei and Sri Pada

Mt. Emei, another UNESCO World Heritage Site in Sichuan province, is one of the four leading Holy Mountains of Chinese Buddhism, known as Chan Buddhism. Samantabhadra is revered as the patron bodhisattva of the Buddhist monasteries associated with the Sacred Mountain. Samantabhadra means “universal virtue” in Sanskrit; Mt. Emei is known as “the greatest beauty under Heaven.” Built in the first century on the location of an originally Daoist temple, it is the home of the first Buddhist temple in China, which has a historical significance as the birthplace of introducing Buddhism to the Middle Kingdom.

In Sri Lanka, the ancient Theravada Buddhists (the tradition of the Elders or the “Lesser Vehicle,” or Hinayana) venerated “Samanta” as the guardian deity of their land and the religion long before Buddhism arrived—with the monk Mahinda, son of Emperor Ashoka—in Sri Lanka in 246 BC. With the northward spread of Mahayana Buddhism (the “Greater Vehicle”), Samanta evolved into Samantabhadra (Puxian in Chinese), one of the four principle bodhisattvas dedicated to the four Sacred Buddhist Mountains in China.

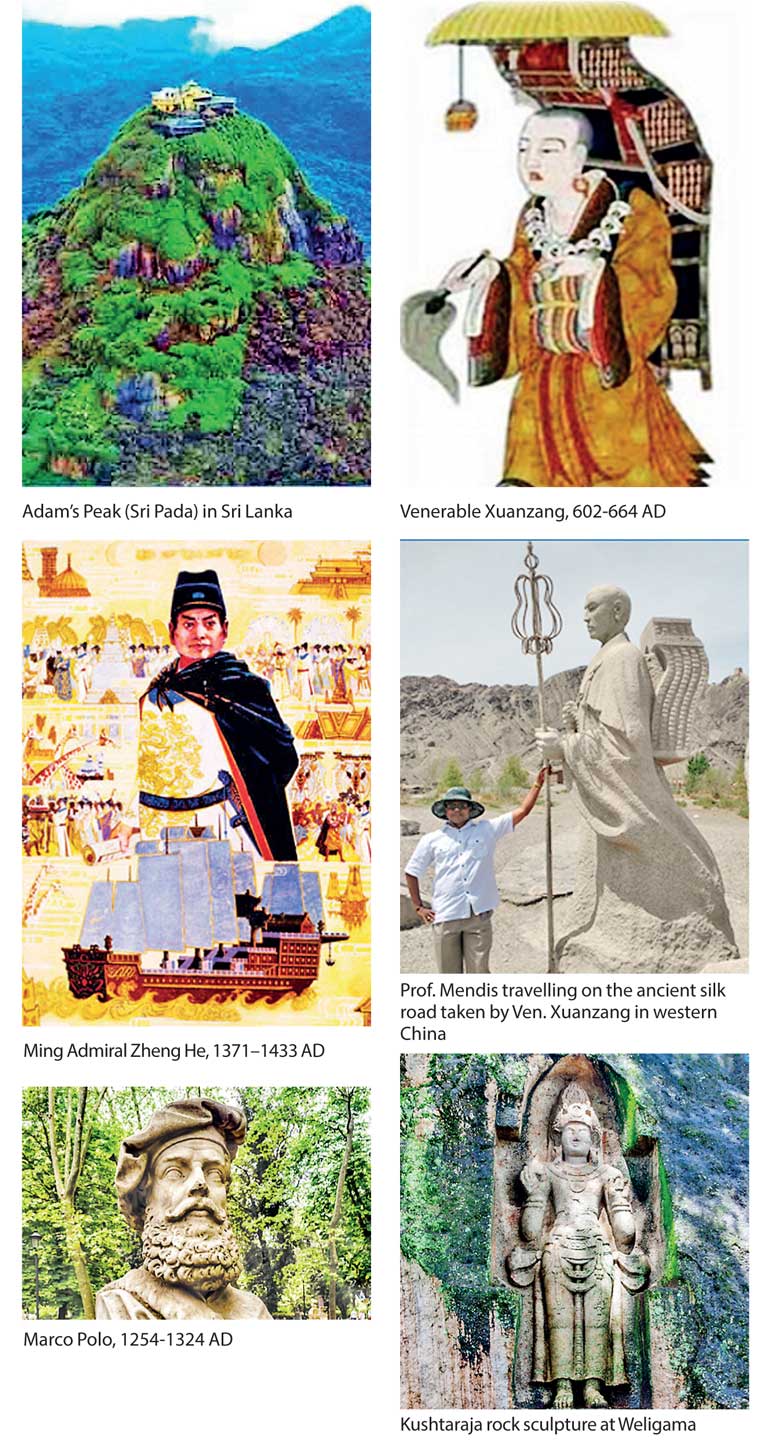

The visiting scholar-monk Faxian in the Kingdom of Anuradhapura wrote that Buddha’s footprint was carved “on the top of a mountain” of the Samanala, referring to Adam’s Peak or Sri Pada (the Holy Footprint) in Sri Lanka. Buddhists believed the Buddha visited the mountain peak and left the footmark while Christians, Hindus, and Muslims equally claimed their own connections—with Adam, Shiva, and Mohammed—to the sacred place for their faith.

Faxian also gave the first-recorded eyewitness account of Buddhist practices, numerous pilgrims, and various foreign merchants in the island, as the Chinese monk stayed at several places, most notably at the legendary Fa-Hien Cave (also Pahiyangala Cave). The erudite monk stayed two years (411-12) at the Abhayagiri Monastery in the capital city, and described Buddhist rituals, drew the pictures of images, and most importantly copied Buddhist sutras.

The Lotus Sutra

Among all Buddhist sutras, the Lotus Sutra is central to Mahayana tradition; the Samantabhadra Bodhisattva is the patron deity. The Lotus Sutra is collectively called the “Threefold Lotus Sutra,” in which the bodhisattva is depicted in holding a lotus flower—a symbol of purity rising from muddy waters—in his hand and travelling with a white elephant that appeared to Queen Maya, the mother of the Buddha. This shared image of elephant—a symbol of wisdom and strength—in various forms is widely displayed in the monasteries of Mt. Emei as well as on the way to Adam’s Peak.

Within the threefold discourse, the Prologue to the Lotus Sutra is the Innumerable Meanings Sutra that explains the true nature of all things in the universe. The Epilogue to the Lotus Sutra is the Samantabhadra Meditation Sutra that refers to the Bodhisattva of Universal Virtue. In totality, the Lotus Sutra holds the final teaching of the Buddha for salvation from human suffering in the present life.

The Lotus Sutra had a momentous impact on China’s hierarchical Confucian culture because it revealed that women, evil doers, and even animals have the potential to become Buddhas or reach Nirvana—the ending of the karmic rebirth and human suffering. In a nutshell, the sutra pronounces equality and freedom, especially among men and women.

Buddhism over Confucian values

The Lotus Sutra was originally translated to Chinese from Sanskrit by scholar-monk Dharmaraksa of Dunhuang in 286 during the Western Jin Dynasty (265-317). The earliest and later translations were revised and completed by Kumarajiva (a son of Brahmin father from Kashmir in India and Kuchan princess in China) in 406. Yale University Sinologist Arthur Wright writes that the equal status of women and mothers in Indian Buddhism was, for example, changed in the earlier translations from “husband supports wife” to “the husband controls his wife” as well as “the wife comforts the husband” to “the wife reveres her husband.”

The prolific monk Kumarajiva, however, revolutionised the evolving Chinese Buddhism without relying on the earlier translations, through the concepts of Confucianism and Daoism, during the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317–420). The surviving Indian manuscripts were nevertheless fragmented but the learned Kumarajiva abbreviated the Sanskrit and Prakrit versions of available Buddhist texts into Chinese.

Like the pioneering scholar-monk Faxian, when Xuanzang (602–64) from Luoyang in Henan province travelled to India in search of sacred books, the Tang envoy was equally concerned about the misinterpreted and incomplete nature of Buddhist manuscripts in China. Even though he never visited Sri Lanka, Xuanzang, who returned to the White Horse Temple in Luoyang, described the ancient capital of Anuradhapura and its Buddhist monasteries, monks, and manuscripts from the eyewitness accounts of travelling pilgrims and merchants. In his Great Tang Records on the Western Regions, Xuanzang—referring to Sri Pada as “Mount Lanka” in the “Sorrow-less Kingdom”—wrote that “the Tathagata [Buddha] formerly delivered the Lankavatara [means ‘Entering into Sri Lanka’] Sutra,” which is another important sutra in Mahayana Buddhism.

While Kumarajiva elegantly emphasised the meaning of the sutras, Xuanzang paid more attention to the literal and precise translations of Buddhist texts. Their central theme of the translations of the Lotus Sutra was focused on “the unity of all things and beings” for a peaceful and harmonious coexistence in freedom.

Colombo as the symbols of lotus

With the rising Lotus Tower from the Beira Lake in Colombo, China has seemingly taken the Buddhist symbol to formulate an enlightened vision for a world of human diversity and equality. In the Anguttara Nikaya, the Buddha counselled a Brahman: “Just as a blue or red or white lotus is born in water, grows in water and stands up above the water untouched by it, so too I, who was born in this world and grew in the world, have transcended the world, and I live untouched by the world. Remember me as one who is enlightened.” This portrayal may have appealed to China as an emerging global power, capturing the ancient legacy connected to the Buddhist nation.

For centuries, the Buddhist “Kingdom of the Lion” attracted foreign visitors and pilgrims who often stopped over the ancient port city of Weligama in the southern coast of Sri Lanka to pay respect to the Samantabhadra Bodhisattva at a temple (near the Kushtaraja rock sculpture), the place of the stone-carved statue of Samantabhadra. Many Chinese and Indian monks and pilgrims had visited the visage of Samantabhadra Bodhisattva on their way to the “sacred footprint” on the summit of Adam’s Peak.

Among them was the famous Admiral Zheng He in the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), who visited the island during his seven voyages (1405-33). The Ming emissary offered gifts to the sacred footprint of Sri Pada, including “1000 pieces of gold, 5000 pieces of silver . . . six pairs of gold lotuses, 2,5000 catties of perfumed oil,” and many other things.

Like the Ming admiral, Marco Polo, an envoy of Kublai Khan in the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), visited the island twice (1284 and 1293) and paid homage to the holy mountain. But his intent was also to take the sacred tooth relics of Buddha back to China. The Temple of Buddha’s Tooth Relics has for centuries been the symbol of national unity and Buddhist identity of Sri Lanka.

For a peaceful identity

As President Xi Jinping has now replaced Deng Xiaoping’s earlier motto of “Peaceful Rise,” Beijing appears to be looking for a “peaceful identity” in creating a harmonious community at home and abroad. The symbolic yet universal meaning embedded in the Lotus Tower might serve better as a strategic asset in Chinese diplomacy, as the BRI gains momentum in the Indo-Pacific region. It invokes the “universal virtue” of harmony, and revives the coveted noble concepts of equality and freedom, rooted in the sutras of Buddhism as opposed to Confucian hierarchy.

During his historic visit to Sri Lanka in September 2014, President Xi described the island as a “splendid pearl” while the two countries have recognised the importance of historic Buddhist affinity with the signing of over 20 cooperative agreements.

Buddhism has always been an invisible attraction as Imperial China successfully integrated the Buddha’s Dharmic teachings as its own with those of indigenous Daoist traditions and Confucian ethics. Therefore, the Lotus Sutra must continue to serve as the forerunner of China’s peaceful identity and national unity for a pacific new order in Asia.

Professor Patrick Mendis, a Fairbank Centre Associate-in-Research at Harvard University, is the author of ‘Peaceful War: How the Chinese Dream and American Destiny Create a Pacific New World Order,’ which is translated to Chinese Mandarin in Beijing. Professor Mendis has visited all the provinces of China and lectured at over 30 Chinese universities and academies, including the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and the universities of Fudan, Nanjing, Peking, Renmin, Shandong, Sun-Yat Sen, Tsinghua, Tongji, Wuhan, Zhejiang, among others. He is a visiting researcher at the National Confucius Research Institute of China in Qufu, a senior fellow of the South China Sea Institute at the Qufu Normal University, a distinguished visiting professor of Asian-Pacific affairs at Shandong University in Jinan, and a senior fellow of the Pangoal Institution in Beijing.