Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday, 1 March 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

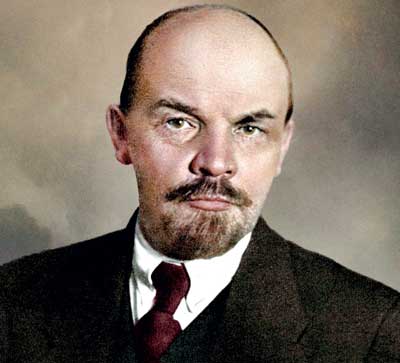

“How could you knead sad Russian dough into any sort of shape? Why was he born in that uncouth country? Just because a quarter of his blood was Russian, fate had hitched him to the ramshackle Russian rattletrap. A quarter of his blood, but nothing of his character, his will, his inclinations made him kin to that slovenly, slapdash, eternally drunken country. Lenin knew of nothing more revolting than back-slapping Russian hearties, tearful tavern penitents, self-styled geniuses bewailing their ruined lives. Lenin was a bowstring, or an arrow from the bow. What then tied him to that country? With a little more work he could have mastered three European languages, as he had mastered that semi-tarter tongue. He was tied, you say to Russia by twenty years as a practicing revolutionary? Yes, but by nothing else” – ‘Lenin in Zurich,’ Solzhenitsyn

In his acclaimed ‘Lenin in Zurich,’ Solzhenitsyn, the Nobel prize winning writer takes us into the torrential stream of Vladimir Ilyich’s (Lenin) thoughts and feelings just a few months before the world shattering revolution of 1917.

Living in exile in neutral Switzerland (the Great War was in its second bloody year), the idea of returning to Russia, leave alone the prospect of a successful overthrowing of the hated Tsar and the system he represented, seemed hopelessly unrealistic to the implacable revolutionary. Years as a refugee, a life of unremitting denials and hardships, ideological conflicts and schisms, the pressures of guiding the activities of an underground party in that enormous and dangerous country from exile and his ceaseless theoretical work had drained him.

“He was nearing the end of his forty-seventh year, in an anxious, monotonous life of nothing but ink on paper, enmities and alliances, quarrels and agreements that sprang up and faded in a day, or a week, all enormously important, all requiring enormous tact and skill, and always with politicians so much inferior to himself, all of it water into a bottomless bucket, instantly lost and forgotten, labour in vain. In a life of constant agitation, twisting and turning, his whole achievement was to fight his way into an impassable rubbish heap.”

Such was Lenin’s gloomy state of mind, only a few months before the October Revolution of 1917 that shook the world. In the confusion brought about by the misfortunes of the war, the Bolsheviks, led by Lenin and a handful of brilliant and capable individuals seized power of the Russian empire. They were convinced that the process thus set in motion would lead to the creation of a classless society, ending exploitation of man by man, the defining feature of hitherto history. History moves to a preordained pattern, and they were the instruments of history.

Under the shock of the revolution, the existing State structure of the gigantic empire had collapsed entirely. Civil war raged over much of Russia, hunger and lawlessness gripped the land. The revolutionary government had no money and the outside world was solidly hostile. Their task was enormous, an undertaking only for men of super-human skills, stamina and courage. For those of us, living our unremarkable prosaic lives, the sheer scope and ambition of the Bolshevik enterprise is mind-boggling. Although the great man in exile despaired of the Russian character, history was to prove him wrong; they were made of sterner stuff.

The mighty land that produced men of the calibre of Lenin and Trotsky, writers with the skills of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, rulers of the scope of Peter the Great and Empress Catherine, outstanding military men such as Zhukov, Bagration and Kutuzov, brilliant inventors and scientists like Popov and Leontiev is not to be sniffed at. In time, the Soviet Union that Lenin established was to become a superpower, the second most powerful country in the world (in only 30 years after the revolution).

True, all this was achieved at a prohibitive price, as so poignantly exposed subsequently by writers like Solzhenitsyn and Pasternak. Man is not some malleable dough to be kneaded into a historically determined automaton. As it evolved, the ideology that the Bolsheviks so ardently embraced proved to be both false in respect of several of its primary premises as well as oppressive in practice. But that does not take away from the integrity and the passion of the original revolutionaries, who gave their all for a greater cause.

On 22 June 1941 when the awesome German army crashed into the Soviet Union in a gigantic thrust, most observers expected the Union to collapse in a few months, if not weeks. Within three short months more than three million Soviet soldiers were captured by the relentless German war machine (almost all prisoners were to perish in captivity). The death and destruction that the Germans unleashed on the Soviet Union is unimaginable.

In four years of fighting Russia was to suffer 25 million dead (equally large numbers were injured or went missing). The titanic struggle for the city of Stalingrad alone, a no-holds-barred battle that went on for six months, resulted in nearly two million dead, civilians included. But the Russians, despite the fearsome mauling they received, did not lay down their arms. With an enormous sacrifice in blood, toil and tears they stopped the Germans, and thereby surely saved the world from a descent into a long night of barbarism.

For perspective, we may contrast the scale of fighting and the Russian losses with the casualties of our own 30-year war with the LTTE which is said to have resulted in approximately 100,000 casualties in this period. That three-decade-long struggle nearly unhinged the Sri Lankan State, its political, economic and social structure brought to near breaking point. After the war’s successful conclusion it seems we can only refer to it in hyperbolic terms. (The world’s best General fighting the world’s most ferocious terrorist group and so on.)

As far as I am aware, Sri Lanka has never caught either Solzhenitsyn’s imagination or Lenin’s intellectual attention. We were too far away and too small to be of any interest to the Russian giants. Perhaps, it is for the best. Had a man of Solzhenitsyn’s sensibilities looked at the ‘thoughts and feelings’ of any of our leaders, he would assuredly be unable to cover the banality of it all in one small volume!

I do not know whether there is an undiscovered Sri Lankan Lenin wringing his hands in frustration at the pathetic realities of his country in Zurich or a more welcoming destination for the natives like Dubai or Singapore (visa on arrival!). Seeing the poor quality of leadership we have produced hitherto, this prospect seems most unlikely (SriLankan Lenin in Dubai!).

But during the years when we were flirting with the Socialist bloc, a story of a particular piquancy did the rounds. Sirima Bandaranaike (the leader of two-thirds of the nations on this earth, as she was described by the Government-owned newspapers in reference to her purely titular position of the then active non-aligned movement) was Prime Minister (1970-77).

The Soviet Union, grateful for the support given by little Sri Lanka at international forums decided to shown its appreciation by asking us to participate in space exploration, an area where it was dominant at the time. Russia was planning to send a rocket far into space and thought it appropriate to allow us gift a dog which would be sent in the rocket and thus earn the honour of being the country from where the first dog to travel in space originated from.

Our Government was elated by this show of favour. Immediately a meeting of high-powered ministers was called to decide on the selection of the lucky dog. The ministers rushed to Temple Trees, helped along by the pilot cars and armed soldiers who cleared the road for them.

As expected of responsible men of the world, the ministers examined the matter deeply and from different angles, leaving no aspect unexamined. Several meetings were held, many of them till late in the night. Small sub-committees were appointed to look into specific areas.

Where should the dog come from, urban or rural? How old should it be? What kind of name should the dog have? Should it have a pedigree? How accurate are the records maintained by the Kennel Club in respect of pedigrees? Having years of experience in electoral campaigns, the ministers exhibited a comforting familiarity with the substance and nuances of such questions.

Eventually, after prolonged discussions, the matter was resolved, with all ministers unanimously agreeing that a pet owned by a relative of the Prime Minister should be the most appropriate dog to represent the country.

Unlike now, the Foreign Ministry then boasted of much talent. A very senior secretary was tasked with the duty of informing Russia of our achievement.

His message to the Kremlin was brief, in the tone of a party which had done all the hard work.

“We have found the dog! Just get the rocket ready!”