Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday, 12 October 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

According to Article 14 of the Constitution, all Sri Lankans have the absolute right to return to their country. If there isn’t enough quarantine space, as the Government is claiming now, they need to fix it – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

By Mimi Alphonsus

To the migrant worker stuck in cramped detention centres eating one meal a day and having just lost a job, the resurgence of COVID-19 in Minuwangoda sparks fear. For them, the new cases signal even further delays in returning home. We worry about being locked-down at home. For migrant workers, that is a luxury.

Of the 1.7 million Sri Lankans abroad, 50,000 migrant workers stuck primarily in the Middle East are trying to come home. Despite the arduous process and small chance of success they have applied for repatriation. Many more will likely follow suit as the situation continues to get worse. Most of these migrant workers have lost their jobs. They don’t have healthcare or proper food. 64 migrant workers have died of COVID-19 and over 2,600 have been infected. Migrant workers have a COVID fatality rate six times higher than Sri Lankans at home (2.4% as opposed to the 0.38%). They are far more at risk than any of us.

Delays in repatriation

In their hour of greatest need, we abandoned them. Sri Lanka halted repatriation flights in July and restricted them to one flight per day in September. I do not need to delve into the horrors of being stuck abroad penniless and helpless. Multiple videos and articles have covered that subject. Instead I will  show how we can and must continue repatriation. Now that another cluster is occurring in Minuwangoda it may seem like the intuitive thing to abandon migrant workers yet again. In reality, this COVID-19 cluster provides an opportunity.

show how we can and must continue repatriation. Now that another cluster is occurring in Minuwangoda it may seem like the intuitive thing to abandon migrant workers yet again. In reality, this COVID-19 cluster provides an opportunity.

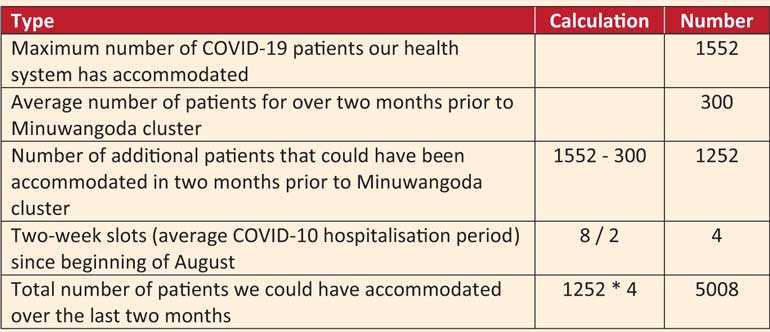

In the box I breakdown our capacity in the months ‘prior’ to the Minuwangoda cluster. I show that we chose not to repatriate more migrant workers even when we could. The Government said we did not have enough quarantine capacity and the risk of infection was too high. I hope that exposing this lie will make the reader critically question the Government when they use similar excuses to halt repatriation now with the Minuwangoda cluster. In summary, we functioned at far less than a 50% capacity for months when we could have instead sped up the repatriation process. To read more on the situation post-Minuwangoda and what can be done, simply skip the box.

The Minuwangoda cluster is a harsh reminder that we cannot return to normal so soon. There is massive community spread and more than 1,300 active cases. It is important in such a time to resist panic and instead think rationally about repatriation. The Government decided to restrict repatriation flights allegedly due to the lack of capacity at quarantine centres and hospitals. This is wrong for three reasons.

First and foremost, repatriates do not create to community spread. They are quarantined on arrival. So, the fear that repatriates are “bringing the disease”, especially when the disease is already rampant, is unfounded. When there is rampant community spread going to the shop is riskier than bringing back migrant workers. Unless a second island-wide lockdown is imposed, halting or stalling repatriation is a disingenuously unnecessary move.

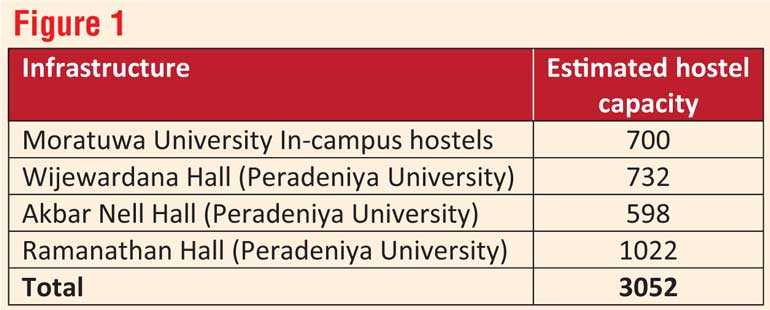

Second, the Minuwangoda cluster has shut down schools and universities. This provides ample opportunity to expand our quarantine facilities. Many times, in the first few months of COVID-19, I went past Royal College and the University of Colombo thinking of how their hostel capacity sat empty and useless. And that’s not to mention their giant non-hostel infrastructure. If only we converted a few well-chosen universities and schools into quarantine centres we could increase our capacity by thousands. This is exactly what states across India are doing. In Kerala they even converted unoccupied houses and government rest houses into quarantine centres. Figure 1 shows a very basic breakdown of just two campus hostels.

But let’s assume that our quarantine capacity is low because of staff, not infrastructure. Many governments sent out urgent calls for volunteers when COVID-19 hit. In Ireland 17, 000 people signed up to volunteer. In Sri Lanka a conservative estimate would bring the number to at least a few thousand. Even if inexperienced volunteers cannot manage a quarantine centre, they can still do other jobs to relieve health staff and transfer them to centres. But the Government has still not called for volunteers.

Say this proposition is unrealistic. Still we can sufficiently increase numbers because running a quarantine centre does not require thousands of staff. Our COVID-19 control has relied unfortunately almost entirely on our armed forces. Surely, we can tap some more into our 280,000 armed forces who at the moment have very little to do defence-wise.

Third, few migrant workers at a time are actually infected with COVID-19 upon return. Typically, there are less than 10 infected repatriates per flight of roughly 500 people. A handful of infections per day is a relatively minor addition to our health system when compared with the hundred that are likely to emerge out of community spread. This is a practical argument leaving aside the fact that an infected migrant worker has as much of a right to be in a Sri Lankan hospital as does anyone infected by the Minuwangoda cluster.

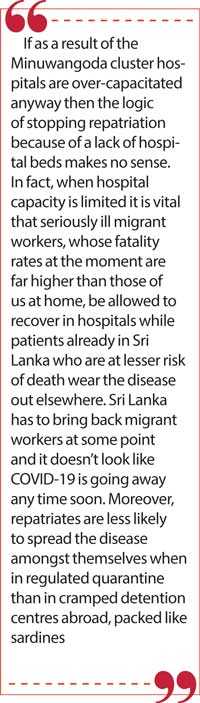

Moreover, it is likely that our hospitals will soon be over-capacitated. This will mean that young and otherwise healthy COVID-19 patients may be asked to recover at home or at makeshift clinics while the seriously ill be treated in hospitals. If as a result of the Minuwangoda cluster hospitals are over-capacitated anyway then the logic of stopping repatriation because of a lack of hospital beds makes no sense. In fact, when hospital capacity is limited it is vital that seriously ill migrant workers, whose fatality rates at the moment are far higher than those of us at home, be allowed to recover in hospitals while patients already in Sri Lanka who are at lesser risk of death wear the disease out elsewhere. Sri Lanka has to bring back migrant workers at some point and it doesn’t look like COVID-19 is going away any time soon. Moreover, repatriates are less likely to spread the disease amongst themselves when in regulated quarantine than in cramped detention centres abroad, packed like sardines.

According to Article 14 of the Constitution, all Sri Lankans have the absolute right to return to their country. If there isn’t enough quarantine space, as the Government is claiming now, they need to fix it. Instead of viewing the Minuwangoda cluster as the perfect excuse to block repatriation again, the Government must seize the opportunity it presents for bringing home our migrant workers.

(The writer is a student of history. Her thesis is on upcountry Tamil migrations to Northern Sri Lanka.)

I would have liked to have gotten a more professional source but since the Government has not released any kind of performance report my simple calculations will have to do. I invite readers to comment any other data they are aware of in the spirit of collective knowledge. There are three main stages in the COVID-19 containment process: quarantine, observation and infection.

Quarantine

First let’s look at quarantine – the most important stage for repatriation. According to the army website, on 2 August there were only 2,047 individuals under quarantine by the tri-forces. On 19 August there were 5,632. That means in the time around 2 August we were functioning far below even half of our maximum capacity. This is not to mention that it is imperative during a pandemic to urgently increase quarantine capacity. Converting under-utilised buildings into quarantine and calling for volunteers are all common strategies for having more quarantine space. The COVID-19 task force did none of these things.

Observation

Second, let’s look at observation. Observation is when a hospital places a person suspected of being infected in isolation. According to the health promotion bureau we observed somewhere between 20 and 50 people on any given day for over a month. But on 9 October hospitals observed a total of 350. That means we were only functioning at 14% capacity at best for months.

Infection

Finally, let’s look at infection. Our COVID-19 designated hospital capacity is 1,552. Since 4 August until the Minuwangoda cluster one week ago we had never had more than 300 active cases in hospital. That is, we had been operating at less than 20% hospitalisation capacity for all of August and September – that’s eight weeks. The average hospitalisation period for COVID-19 is 16 days or around two weeks. Had we not simply dilly-dallied at 20% capacity for two months we could have accommodated over 5,000 infected migrant workers before the Minuwangoda cluster hit.

The Chief Epidemiologist, Dr. Sudath Samaraweera, confirmed that in and around May we had extended COVID-19 care to 10-15 hospitals. By September COVID-19 patients are only treated in three. This is a gross underuse of our capacity when thousands of our citizens were sick abroad without proper shelter, let alone a hospital.