Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Friday, 5 March 2021 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

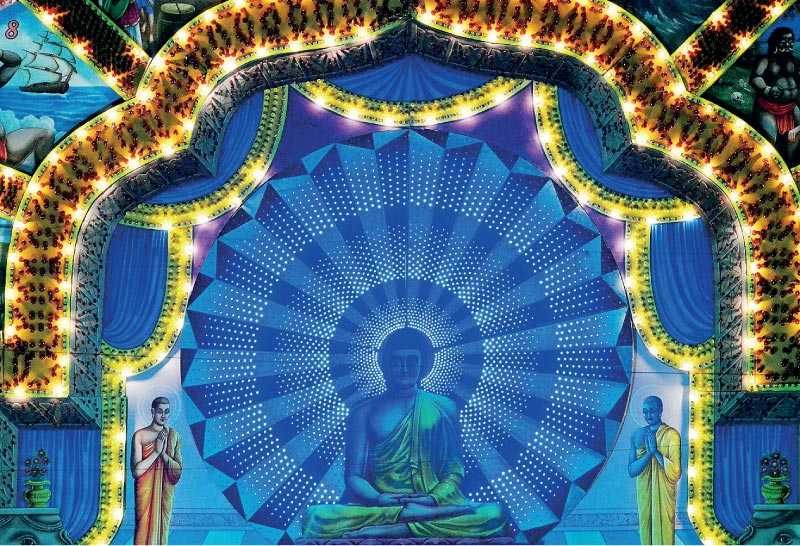

The distortion made by the system of these beliefs in the minds of Sinhala Buddhists people is immense. So much so, the arrogant attitude they have cultivated in thinking that all the other ethnic groups are inferior to them has a huge detrimental effect not only on the non-Buddhists but also on the Sinhala Buddhists themselves – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

The article which I subscribed to the FT Columnist last week, titled ‘The end of an era of extremism’ to demonstrate that the potentiality of the Sinhala-Buddhist racist ideology as a political movement and its social acceptance, has now reached a historic end, seemed to have aroused a considerable public interest. In this article, I hope to point out the false foundations on which this extremist racism which, in the name of Sinhala Buddhism, has thrived in various forms for more than a century reaching at the peak of its power whilst at the same time heading towards a historic end.

The article which I subscribed to the FT Columnist last week, titled ‘The end of an era of extremism’ to demonstrate that the potentiality of the Sinhala-Buddhist racist ideology as a political movement and its social acceptance, has now reached a historic end, seemed to have aroused a considerable public interest. In this article, I hope to point out the false foundations on which this extremist racism which, in the name of Sinhala Buddhism, has thrived in various forms for more than a century reaching at the peak of its power whilst at the same time heading towards a historic end.

Ideological backwardness, a common issue

The ideological backwardness explicit in regard to the communal crisis of Sri Lanka was not limited to the community of Sinhalese only. All indigenous ethnic groups except the Burgher community were accustomed to perceive this issue from a very backward and tribal attitude. Only the leaders of the Burgher community had a broader liberal vision about it.

There were many who were educated in the West among the prominent leaders who had entered politics in Ceylon from the time of the founding of the Lanka Jathika Sangamaya in 1919 (Ceylon National Congress) up to independence; but none of them could be considered as being conversant with or influenced by liberalism. Even Ponnambalam Arunachalam, comparably the most advanced person among the leaders of the Lanka Jathika Sangamaya of its early days could not be considered a Liberal leader.

The Sinhala leaders of Goyigama caste supported Ponnambalam Ramanathan at the election held in 1911 in selecting the educated Ceylonese representative for the Legislative Council solely because they wanted to prevent the candidate of the Karava caste being appointed to this respectable high post. It was no secret for Ponnambalam Ramanathan. He was well aware of the intention of the Sinhala leaders of Goyigama caste.

Meantime, Ponnambalam Arunachalam, in an article written by him, had stated that the Goyigama and Vellala castes were the dominant denominations of the castes system in the Sinhala and Tamil society respectively. In this backdrop, Ven Weligama Sumangala Thero wrote a book on the history of the Karava caste asserting that Karava caste was superior to the Goyigama caste, which eventually led to a heated and controversial debate on the caste system in Sri Lanka. Ven Weligama Sumangala Thero had used the above statement made by Ponnambalam Arunachalam as an opening excerpt in his book.

Despite ethnic divisions prevailed between Sinhalese and Tamils, still the leaders of both Sinhala Goyigama caste and those of Tamil Vellala caste found themselves in the same camp when it came to the caste disputes in Sinhala and Tamil society.

Growth of literacy

It is interesting to note the way the ethnic and religious divisions have emerged as the main element in the social divisions in Sri Lanka subduing the dominance held by caste divisions. The transformation of Lankan society into a literate society commenced with the gradual entry of the country into the modern era. The first phase of this transformation took place during the time of Anagarika Dharmapala.

In 1880, there were only 93 English schools in Sri Lanka. By 1911-12, this number had increased to 242. During this period the number of students enrolled in English schools had quadrupled from 8,887 to 35,389. During the nine-year period from 1880-89, 292 students sat for the Cambridge Senior Examination while for the six years from 1910-16, the number had increased to 2,644. How the society had been transforming into a literate society is evident from these statistics.

The literacy rate in Ceylon stood at 26.6% for men and 2.5% for women in 1881. By 1911, it had grown up to 40.4% for men and 10.6% for women. But even by 1911, the national literacy rate of English language remained as low as 3.3%. However, by 1911, the literacy rate in native languages (Sinhala and Tamil) had risen to 37.1 and 7.3% for males and females respectively. A significant proportion of native population had acquired a good knowledge of information published in Sinhala and Tamil languages. But they had to seek assistance from an intermediary who knew English to get things published in English deciphered and explained.

Historiography of Sri Lanka

The historiography of pre-modern Sri Lanka can be considered as the first phase of the recording of the country’s history while that of modern Sri Lanka can be considered as the second phase of it. The publication of a number of excellent books on the history of Sri Lanka by several civil servants of the British administration in Sri Lanka has been one of the most significant developments in the field of history since Sri Lanka has entered the modern era. These books can be considered as the forerunner that inaugurated a dialogue on the history of modern Sri Lanka.

George Turner who had acquired an expert knowledge in Sinhala, Tamil and Pali languages, having discovered the commentary on the Mahavamsa, the ancient chronicle of Ceylon, wrote and published two books, one on the short history of Ceylon and the other, a critical analysis on the Mahavamsa. John Doyle wrote on the constitutional tradition of the Kandyan Kingdom. James Emerson Tennant published a book entitled ‘History of Ceylon’ in two volumes which can be considered as an encyclopaedia of the history of Sri Lanka. Also, H.W. Codrington published the first critical work on the history of Ceylon.

There were several other factors that contributed to arouse a great social interest in the history of Ceylon. The British government launched a comprehensive program for identifying, mapping and photographing the historically significant ruins in Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa areas, which have been devastated by the ravages of time and incessant jungle tide for centuries. The reports published about these discoveries and excavations aroused public interest.

Also, Muller Edward, a German professor was assigned the task of discovering and copying ancient inscriptions. A collection of inscriptions copied by him was published in 1881 as a book titled ‘Ancient Inscriptions in Ceylon’. Thus, archaeological research programs were initiated and maintained; and in 1890 a Department of Archaeology was established for this purpose.

Wilhelm Geiger, a German professor, published an English edition of the Mahavamsa, and a book on the historical development of the Dipavamsa and the Mahavamsa. Professor Wilhelm Geiger was appointed for this purpose and the costs incurred were defrayed by the British government. It was also the British government that assigned Ven Hikkaduwe Sumangala Thero and Pandit Don Andrews Silva Batuwantudawe, the responsibility of translating the Mahavamsa into Sinhala and published it as a book.

Distortion of history

It was the British themselves who told us that Sri Lanka had a long history and an advanced civilisation that we could be proud of; and our forefathers were clad in woven cloths when the English used to cover their bodies with herbal leaves. But, the contents of things the British narrated to us and the reports they published on discoveries they made were all in English and it was Dharmapala, Walisinha Harischandra and their disciples who interpreted them to the majority Sinhala people who did not know English.

They made the unsuspecting ordinary Sinhalese people to believe that the Sinhala Buddhist community in Sri Lanka was the greatest and the noblest of all the peoples of the world; and the historical discoveries and findings have proved that the ancient civilisation of Sri Lanka was the greatest and the most splendid civilisation in the world.

Although Anagarika Dharmapala could be considered as a formidable missionary, a preacher of the Dhamma, he cannot be ranked as a good scholar. He did not have an objective knowledge on the subject of history. But his Sinhala Buddhist followers acknowledged him not only as a prominent leader who fought for the rights of the Buddhist but also as a great scholar who knew everything.

Institutionalising the myth

So far, no research institute in the world has conducted a study on the greatest ethnic group in the world. There is no doubt that Sri Lanka had an advanced ancient civilisation. But it is not included in the category of the 10 most advanced ancient civilisations in the world. Let alone being the most advanced civilisation in the world! Yet, the interpretation of Anagarika Dharmapala was not only accepted by the ordinary Sinhala Buddhist people as an authentic historical fact, but also by the historians of repute as well. Perhaps this may be due to their reluctance or fear to challenge the superstitious views rooted in the minds of the people by Anagarika Dharmapala.

The impact made on the Sinhala Buddhist attitudes by these teachings on history is deep and profound. Although we live in the 21st century now, the majority of Sinhala Buddhists still believe that there was a close blood relationship between King Vijaya and the Lord Buddha.

Vijaya and his followers arrived in Sri Lanka with the guidance and blessings of the Buddha and on the day of Buddha’s Parinirvana, the passing away. The Buddha had allegedly told the Sakka, the Lord of gods that the Buddhism, after his passing away would be established and preserved in Sri Lanka and hence to provide protection to Vijaya and his followers. Eventually, this combination of Buddhism and Sinhala race resulted in generating the greatest and the noblest ancient civilisation in the world during the periods of Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa.

The distortion made by the system of these beliefs in the minds of Sinhala Buddhists people is immense. So much so, the arrogant attitude they have cultivated in thinking that all the other ethnic groups are inferior to them has a huge detrimental effect not only on the non-Buddhists but also on the Sinhala Buddhists themselves. This extremist program that has been pursued in the name of Sinhala Buddhism for more than a century has reached its peak now, and is simultaneously falling to the lowest level of its failure as well. This phenomenon should be understood as a unique scenario in which Sri Lanka has come to a historic end of one ugly and gloomy era, paving the way for heralding a new era, which will be beautiful and fair.