Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Wednesday, 26 September 2018 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

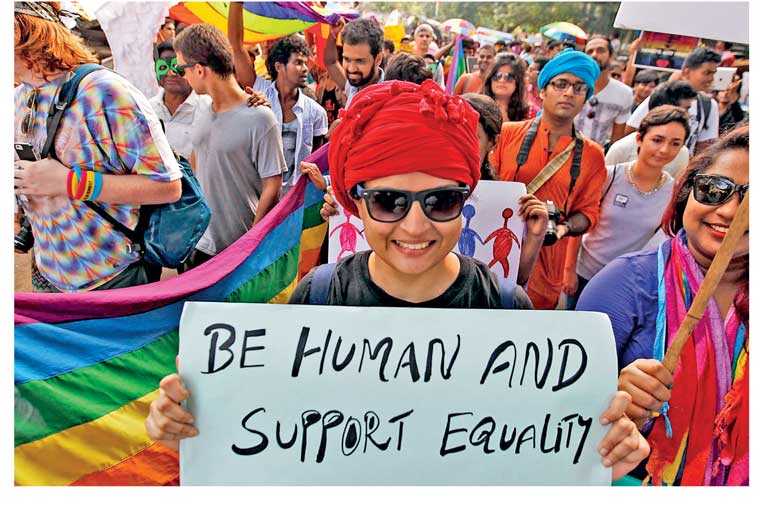

The last Cat’s Eye column observed all that there is to celebrate in the recent Supreme Court of India’s judgement on Sec. 377, which decriminalised adult consensual same-sex sexual activity in private. We used this ‘magnificent’ decision, whose scope is much broader than the rights of any one group of citizens, to comment on related judgements in Sri Lanka.

The last Cat’s Eye column observed all that there is to celebrate in the recent Supreme Court of India’s judgement on Sec. 377, which decriminalised adult consensual same-sex sexual activity in private. We used this ‘magnificent’ decision, whose scope is much broader than the rights of any one group of citizens, to comment on related judgements in Sri Lanka.

Today, Cat’s Eye wishes to focus on the connections between India and Sri Lanka, and indeed South Asia, in the fight for social justice. These connections are not ONLY because we share the same oppressive law (Sec. 365 and 365A, Sri Lankan Penal Code) but also because we were part of the fight to change it. This judgement is far from being a mere legal victory. It is a victory of the LGBTIQ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex, Queer) movement that has existed for many decades in many forms. These movements have often transcended national boundaries.

The wandering mind is on its way to see a dream…

In this crazy world, I wish I had some crazy company…

With this scheming crowd around, I wish your hand was in mine…

Swanand Khirkire (Translation: http://yashraj.tumblr.com/post/1985487219/baanwara-mann-the-wandering-mind-hazaaron)

This song was claimed by queer activists in many parts of India for their movement. They sang it loudly, with passion, even if not to melody, whenever and wherever. Among them was a Sri Lankan trying to keep up with the pronunciations but singing with gusto, alongside her loved ones.

Priya Thangarajah studied law at the National Law School of India University, Bangalore. Her legal mind and her queerness drew her into the spaces in Delhi and Bangalore that were at the centre of the fight against Sec. 377, working on queer rights and broader social change. In her own words:

“While I found feminism through a great upheaval in my life, I found queerness through love.”

She went on to co-write academic works on the law and the lives of queer women and trans people such as ‘The love that blinds the law: Queer Women and Habeas Corpus in India.’ Priya has since passed away and on the day of the Supreme Court judgement, her fellow queers in India made a meme with a picture of her and declared “We finally made it, Priya!”

Priya was not the first or only Sri Lankan activist to be part of these cross-border relationships, loves, and movements for social change.

Sunila Abeysekera and Amrita Chachchi, who are among the many foremothers of feminist movements in Sri Lanka and India respectively, have written on this history. They speak of the ‘first encounters between South Asian feminists in the 1980s and the process of creating an affective South Asian feminist community.’ They use Kumari Jayawardene’s idea of ‘sisterhood as a newly formed feminist constituency’ to describe the imagining of intimate chosen kin relationships between South Asian feminists across borders.

Across South Asia, ideas of isolated identities and their rights rarely bound these struggles. They saw that just as much as systems of oppression are connected, so are the struggles for justice and freedom. In the South Asian context, those working on sexuality were always asked: “when there is no food, shelter or peace, how can you talk about sex and sexuality?”

This question led many across the region to do the work of establishing that gender, sex, and sexuality-related issues are as significant as all other basic human rights. This process was grounded in our culture of movements for social change that didn’t isolate issues from each other but saw them as connected: peace and economic rights; environmental justice and gender issues, etc. For the most part, LGBTIQ movements in South Asia have followed that legacy.

The queer movement in India, for example, has always made its connections amply clear to movements advocating for justice for women, children, oppressed caste communities, the poor, workers, and other marginalised communities.

Voices in the queer movement have stated repeatedly that it stands for democracy and against authoritarianism. It has made clear that it will always strive against complicity in the practices of marriage and family that deny freedom and choice but reaffirm caste, class, and gender-based privilege.

These voices propose a love that is based on radical equality and social transformation. It is this spirit, insisted upon by the movement, which has now been reflected in the Supreme Court judgement in India.

In Sri Lanka, the history of women’s movements for social change and justice also highlights the interconnectedness of struggles.

Sunila Abeysekera, while documenting the lives of women in workers’ struggles in the early 1980s, in Aragalaye Isthrihu’s ‘Women in the Struggle’ (1988), writes of the coming together of student movements, workers, farmers, women’s rights, and democratic movements in the face of growing authoritarian rule, massive economic restructuring, and state sanctioned violence and riots.

She noted that in the vibrant discussions around the organising of the International Women’s Day in 1983, the themes included supporting the women workers who were striking against Polytex Garments, as well as the call to repeal the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA); along with the demand to release Nirmala Nithiyanandan, the sole woman who had been arrested under the PTA at that time.

Similarly, Priya describes the queer movement in Sri Lanka as follows:

“LGBTIQ persons deserve dignity and respect; our deviance, which is built on consensual adult sexual activity, should be celebrated. Our movement, while focusing on decriminalisation, must also ensure that persons refused employment and health care due to their gender non-conformity are able to access these services with dignity……the LGBTIQ movement in Sri Lanka has worked at the grassroots level and, to date, our community consists of people from various walks of life.”

The legacy of this practice and its strength was apparent in the submissions made to the Public Representations Committee as part of Constitutional Reform process in 2015.

In submissions from different districts of the country, alongside demands for a secular state, acknowledgement of women’s care work, rights related to social security and justice for those affected by enforced disappearances, women proposed to add that there “should not be any discrimination based on pregnancy, civil status, widowhood, sexual orientation, sexual and gender identities.”

In Batticaloa, for example, women specifically recommended that “sexual rights, rights to bodily integrity, reproductive health and rights, and the right to decision-making on abortion, should be guaranteed for women in the constitution.”

Recommendations made by the LGBTIQ community in Sri Lanka to the Consultations Task Force on Reconciliation Mechanisms, strongly articulated the connection between queer rights and the need to curb militarisation. The submission reads as follows:

“Militarisation creates and boosts very stark models of masculinity and femininity and forces people into adopting extreme binary gender conforming roles. This is particularly limiting for people who do not conform to such gender roles. In addition, militarisation paves the way for these rigid gender norms to be connected to reproductive sexuality (where sexuality is confined to the logic of reproduction–within marriage and the monogamous heteronormative family unit) and its role in the rhetoric of ethno-nationalism”.

We celebrate the Indian Supreme Court judgement as it gives hope to the continued struggle for affirming the rights of LGBTIQ persons in Sri Lanka, while establishing an understanding of constitutional rights as ‘transformational’ only when interconnected and holistic. This hope is precious as we are yet to see any sight of affirming broader human rights for all through a new constitution in Sri Lanka. We still await any real accountability for injustices committed during the war.

In India, as the 377 judgement was being announced, there were thousands of farmers occupying the streets of Delhi demanding a minimum wage and food security. Simultaneously, prominent human rights activists, poets, academics, and lawyers were being criminalised for organising and advocating for the rights of marginalised people who are brutally oppressed by the current regime in India.

Therefore, our activism and critique must maintain its ethos of interconnectedness to effectively demand justice and freedom for ALL. We hold our collective victories close, as hard won and precious. Human history has shown us repeatedly that ‘none of us are free till all of us are free.’ We must constantly re-imagine and strengthen our solidarities across national borders towards a radical equality and the ‘right to love.’

At Cat’s Eye, we recognise the importance of putting our energies into building those chosen relationships of love and camaraderie, so that our politics can stand strong in the face of authoritarianism, violence, and the increasing challenges against basic socio-economic and political rights of the marginalised in Sri Lanka and the rest of South Asia.

Cat’s Eye awaits the day when we too can experience a legal victory in Sri Lanka, affirming the rights of LGBTIQ persons. Meanwhile, we are glad to be a part of this vibrant ongoing legacy of the interconnected nature of struggles.

The right to love is the right not to conform to the norms of social hierarchies. The right to love is the right to imagine a world where ALL persons can live ‘full lives’ with justice, freedom, and dignity irrespective of their caste, class, gender, ethnicity, religion, or sexual orientation.

(The Cat’s Eye column is written by an independent collective of feminists, offering an alternative feminist gaze on current affairs in Sri Lanka and beyond.)