Friday Feb 27, 2026

Friday Feb 27, 2026

Monday, 8 January 2018 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The story so far

The former Finance Minister Ravi Karunanayake, in an interview with Daily Mirror, had put the Central Bank’s management on its toes by making some scathing allegations against the bank (available at: http://www.dailymirror.lk/article/Central-Bank-is-absolutely-corrupt-and-inefficient-Ravi-Karunanayake- 142963.html). His main charge, among many others, has been that the bank is “absolutely corrupt and inefficient”.

142963.html). His main charge, among many others, has been that the bank is “absolutely corrupt and inefficient”.

In the previous part (available at: http://www.ft.lk/columns/Ravi-K-s-critique-of-Central-Bank--An-instance-of-rendering-the-blame-unto-Caesar-/4-646279 ), we looked at specific charges made by Karunanayake, namely, the issue of the Central Bank’s autonomy, the bank’s failure to tame inflation and making the Prime Minister answerable to the people for action which the bank had taken without consulting or informing him.

Charge is not against bank but against Monetary Board

It was noted that when Karunanayake criticises the bank, he is in effect criticising the Monetary Board which is the legal authority over its affairs. Then, it becomes an awkward criticism since he himself had had a hand in appointing its members. The politicians can appoint the Board but, once appointed, they cannot interfere in its affairs, a precaution taken by Parliament to safeguard the moneys owned by people.

Inflation is largely Government’s making

Though it was true that inflation was rising at present as alleged by Karunanayake, such inflation has been the result of the heavy borrowing he had made from the Central Bank and commercial banks amounting to Rs. 550 billion while he was the Minister of Finance. It was equated to a kid helping himself to cookies placed in a jar sans a lid. The Board has been granted autonomy by Parliament to discipline the kid by tightening the lid as it thinks fit.

Finance Minister has failed to apprise PM

If the Prime Minister has been kept in the dark about the policies adopted by the Monetary Board, that again is due to the failure of the Secretary to the Ministry of Finance, an ex-officio member of the Board, to apprise the Minister of Finance and if he has done so, the failure of the Minister to apprise the Prime Minister.

Karunanayake has also charged that it is the Central Bank which is responsible for the current low performance in the economy. This part will look at how far this charge is justified.

Economic slowdown began in 2013

In the three years following the end of war in 2009, Sri Lanka had had a high economic growth of above 8%. This was a reversal of the declining growth rate recorded by the country since around 2006. In 2009, it had fallen to the lowest level at 3.5%.

Hence, the boom experienced during 2010-12 could be considered a non-repeatable bonus delivered to the country in the form of a peace dividend. Since 2013, the country could not sustain this growth since it had failed to carry out the needed economic reforms to place the economy on a continuous growth path.

Accordingly, growth fell to 3.4% in 2013, but slightly recovered to 5% in 2014, a rate still not high enough to make Sri Lanka the Wonder of Asia as claimed by the previous Government.

Present Government failed to reverse the trend

When the new Government was formed in 2015, its task was to sustain and accelerate this rebounded growth. However, growth fell to 4.8% in 2015, to 4.4% in 2016 and to an estimated 3.8% in 2017.

It is this falling growth rate about which Karunanayake had expressed his dissatisfaction and sought to blame the Central Bank. He should be doubly unhappy since the Government promised to increase the growth rate to 7% or above and sustain the rate at that level till 2045 to make Sri Lanka a rich country.

With faltering growth at the beginning, the country will have to raise growth to a level well above the minimum needed to attain the goal of becoming a rich nation within three decades.

Belief that Central Bank printed money can bring growth

But what brings economic growth? Growth comes from the expansion of the total output at a high rate year after year. However, there is another side to this story for it to become continuous. That is, there should be people, whether in Sri Lanka or outside, to buy this output so that producers can continue to produce it uninterrupted. The production side is known as aggregate supply and the demand side is known as aggregate demand. The issue at hand is whether a central bank can influence the supply side through the policies available to it. Karunanayake seems to believe that the Central Bank can do it.

The underlying reasoning is that when people and the Government spend money, created by the central bank and commercial banks, on goods and services, the aggregate demand will increase, prompting producers to step up production and create income for people.

The credit for promoting this rationale goes to early 20th Century British economist John Maynard Keynes, who came up with a policy to tackle temporary economic depressions and not for sustaining permanent economic growth. But politicians, especially those in developing countries, immediately embraced it since it gave them a ‘magic wand’ to quickly deliver economic growth to their respective nations.

Karunanayake cannot be blamed for believing in this ideology since all his predecessors, except M.D.H. Jayawardena who held that portfolio during 1954-55, practised it to the letter.

However, if this belief was correct, Sri Lanka should have been a developed country by the 1970s, since it had been the strategy adopted by all successive governments since independence.

But excess money creates inflation and leaks out of the country

The Central Bank-printed money can cause only a temporary increase in supply. The money made available to businesses in the form of working capital will help them to maintain the output at the prevailing level. Similarly, money in the form of investment capital will allow an economy to expand the output. The first one is avoiding economic recessions; the second one is causing economic growth.

However, for the output to sustain there should be a continuous demand for same. But that demand should be backed by the real income of people supported by the real goods and services they have produced. If it is backed by money income, the result will be an increase in the price level and not the real output. When only the prices increase there is no incentive for producers to continue to increase the real output. That is how money induced growth becomes temporary.

With people having money in their hands but no increased local supply, the increased demand leaks out of the country by way of imports. It creates balance of payments difficulties, erodes the country’s foreign reserves and puts pressure on the exchange rate to depreciate. This is exactly what happened to Sri Lanka in the entire post-independence period.

In the case of prices, they were at 100 in 1952 according to the old Colombo Consumers Price Index. When the index was abandoned in 2007, they had risen to 5,416. When adjusted to the new index, the comparable overall price level jumps to 10601 by end 2017. Thus, a rupee in 1952 is worth only a fraction of a cent today.

As for the exchange rate, at the time of independence, a US dollar was worth Rs. 3.32 or a rupee was worth 30 US cents. In January 2018, a US dollar is as expensive as Rs. 155 or a rupee is as worthless as about a half of a US cent.

It was simply a one-way upward journey for prices and a downward journey for the exchange rate.

Both John Exter and D.S. Senanayake warned against irresponsible money printing

However, this bad experience is not something unknown to Sri Lanka’s Finance Ministers even at the time of independence.

The founding Governor of the Central Bank – John Exter – in his very first press briefing in 1950 after the bank was established issued the following warning: “Today, we can only be filled with high hopes for the future. It would be a mistake to expect startling results immediately from the establishment of the central bank. There is no financial wizardry by which the bank can suddenly pull out of a hat a higher standard of living for everybody. The bank’s contribution must necessarily be a long run contribution. The bank does not itself produce goods and services, but it should, by creating the right monetary conditions, enable the country to do so.”

The same message was delivered by the then Prime Minister, D.S. Senanayake, known as DS, in his speech at the opening of the Central Bank. DS warned the Central Bank’s management against irresponsible money printing and becoming bankrupt like Greece at that time.

Singapore’s top brass never believed in growth through money printing

About one and a half decades later, Singapore’s top brass of politicians too had to make this choice when they separated from the Malay Federation in 1965.

As reported by Singapore’s first Finance Minister – Goh Keng Swee – in 1992, none of his Cabinet colleagues “believed that Keynesian economic policies could serve as Singapore’s guide to economic wellbeing”. He further said that Singapore was a small open economy and if budgets were financed through money printed by the central bank, it was an invitation to disaster.

The conviction of the Singapore’s top brass was that prosperity could not be created by central bank-printed money. Instead, prosperity came from hard work done by all Singaporeans alike. So the Government, instead of relying on central bank-printed money, created conditions for all Singaporeans to work hard.

This wisdom is missing in economic policymaking in Sri Lanka throughout the post-independence period. That was because good economic wisdom was not considered as good political wisdom by the country’s successive political masters. Hence, they continued to play a short-term political game. Accordingly, Karunanayake has not been a lone game-player.

This Government’s economic policy strategy has no room for money printing

However, the economic policy strategy pronounced by Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe in two policy statements delivered in 2015 and 2016 and his Vision 2025 has been a departure from the ‘central bank-printed money ideology’.

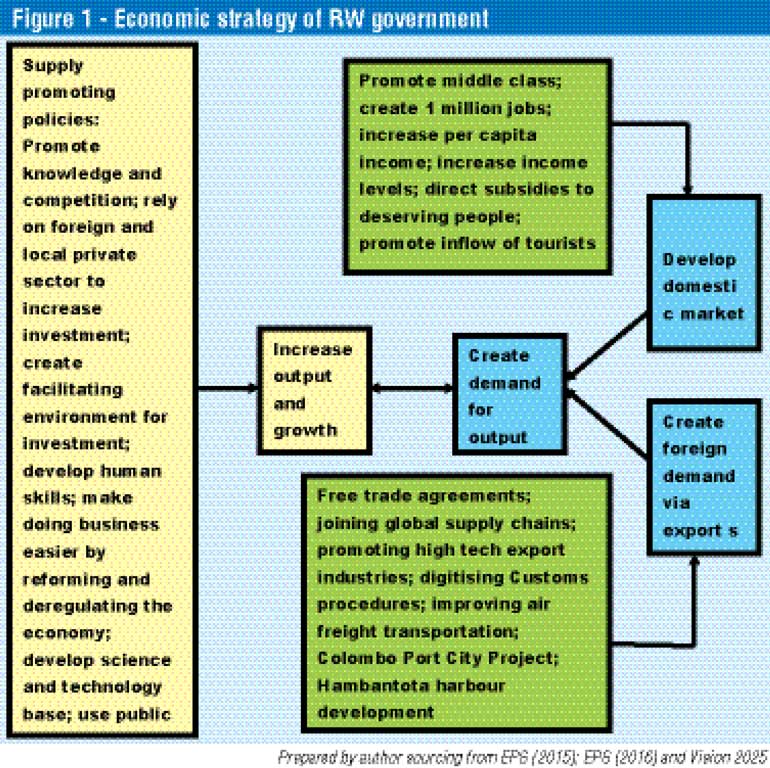

As shown in Figure 1, Wickremesinghe has proposed to increase the total output of goods and services, known as the aggregate supply, by getting the local and foreign private sector to invest in strategic sectors. To create conditions for them to invest, he has proposed to improve the country’s human capital base, physical infrastructure and science and technology base. This increased output should be demanded by demanders and since the country’s domestic market is puny in relation to major industries with economies scale, it should be done by creating sizeable foreign demand, known as exports, for the local output.

Wickremesinghe elaborated on this by saying that Sri Lanka should produce for a market bigger than that in Sri Lanka, meaning the large global market out there. That was why he proposed to sign trade agreements with every country possible.

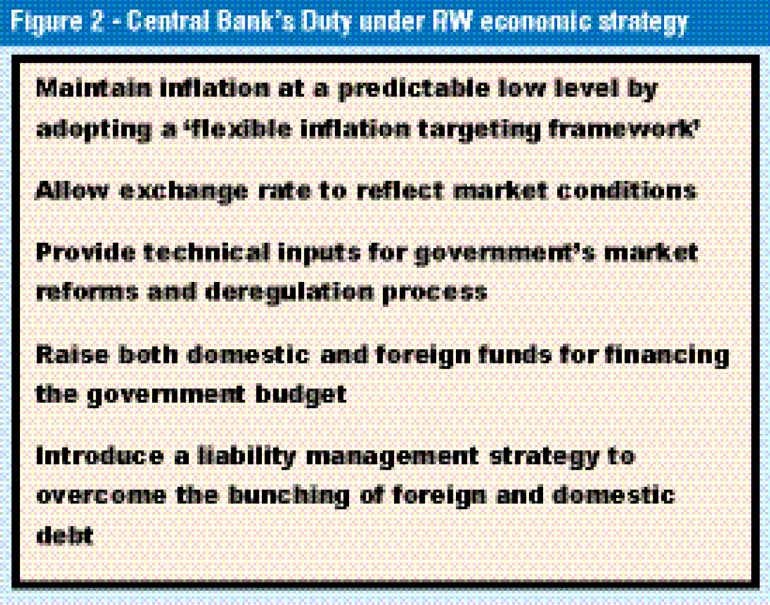

The role outlined by Wickremesinghe for the Central Bank, as shown in Figure 2, does not have money-printed growth. Instead, the strategy has endorsed the bank’s move to flexible inflation targeting in which the creation of money would be kept under strict control by the bank. To raise funds for the Government, the strategy has been to increase revenue, especially tax revenue.

Budgets that are not aligned with the policy strategy

When this strategy was announced in early November 2015, Karunanayake was expected to align the Budget which he presented later in the month with its goals. However, as this writer pointed out in an article in this series, his Budget was completely out of alignment with the Government’s accepted policy framework (available at: http://www.ft.lk/columns/budget-2016-has-it-laid-foundation-for-implementing-the-policy-outlined-in-eps-of-yahapalana-governm/4-499447 ).

The policy strategy required Karunanayake to lay the foundation for changing the structure of tax revenue from indirect to direct taxes. However, the budgetary outcome for 2016 was starkly in the opposite. It proposed to increase indirect tax revenue from 80% to 87% and reduce direct tax revenue from 20% to 13%.

At a time when the Government had been stuck for funds, the Budget 2016 had proposed two other white elephants in the style of another state university and another state-owned export import bank.

Budget 2017 presented by Karunanayake at the end of 2016 was another misalignment as argued by this writer in another article in the series (available at: http://www.ft.lk/columns/budget-2017-significant-improvement-if-not-marred-by-policy-inconsistencies-and-interference-with-th/4-580074).

The proposal to give free tablets to students could be considered a political game rather than an economic necessity. On top of this, Karunanayake proposed to introduce a tax on cash withdrawals from banks justifying that it was to discourage cash usage and promote a cashless society.

Central Bank’s only power is to print money

The only power which the Central Bank has is the power to print money. Without a proper economic infrastructure in place, such money created will not help the country to increase its real output but will be leaked out of the country via imports.

Instead of avoiding this, Karunanayake sought to finance a sizeable segment of his Budget via bank-created money during 2015 and 2016. In these two years, his borrowings from the banking sector consisting of the Central Bank and commercial banks increased by Rs. 550 billion, adding new money to the economy.

This was done at a time when the broad money supply used by the Central Bank for its policy purposes, known as M2b, was rising at an average rate of 18% per annum and real growth was about 4.5%.

The resultant excess demand for goods and services was to put pressure for prices to rise and the exchange rate to depreciate. This was exactly what Sri Lanka experienced in 2017 with inflation rising to 8% and the rupee falling by about 3% against the dollar by the end of 2017.

Karunanayake should have listened to Central Bank’s advice

The slow economic growth during 2015-2017 was due to the failure of the Government to implement the needed economic reform program. The Central Bank had advocated for this in its annual reports for both 2014 and 2015. Failure to appreciate these policy recommendations and introduce a suitable mechanism for the same has caused Sri Lanka’s economy to land in the present slow growth region.

Thus, instead of passing the blame on to the Central Bank, the top brass of the present Government should go for ‘a self-criticism exercise’ and move fast in implementing the reform agenda and create an investment friendly environment to attract both local and foreign investors.

(W.A. Wijewardena, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected])