Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Thursday, 20 August 2020 01:14 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

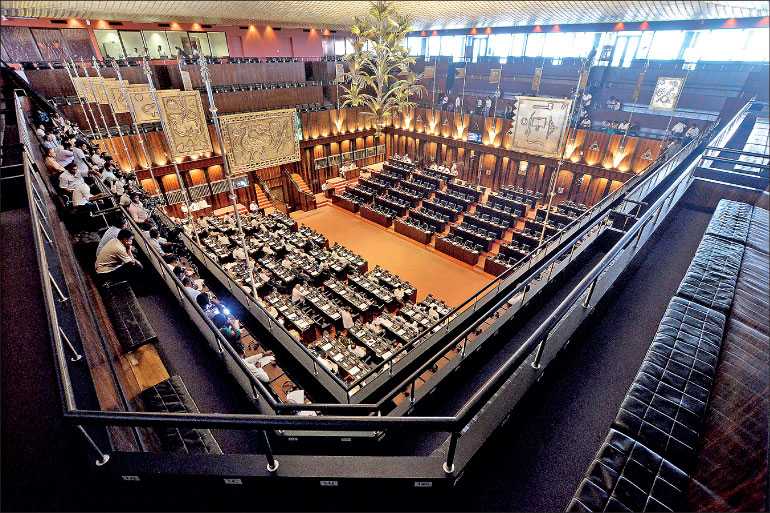

There is no reason to go back to what did not work. There are more important things the government can focus on, especially given the massive majority in Parliament and the challenges posed by a contracting economy and debt repayments coming due – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

It appears from news reports that the new government considers the impending debt crisis less important than hacking away at the 19th Amendment. It is ironic that those who opposed the 1978 Constitution are seeking to restore its worst elements.

Power to dissolve Parliament

Under the 1978 Constitution, the President is directly elected by the people. His mandate is independent of Parliament. Parliament derives its mandate also from the people, independently of the President. Unlike many other countries, we must conduct two elections at considerable cost to figure out the shape and form of our government.

One could debate the rationality of conducting two expensive elections within a few months and about the strain imposed on the economy and polity by the associated uncertainties. Each election has two cost components: one incurred by the state for its conduct (estimated to be more than Rs. 8 billion for the 2020 General Election) and the total of the costs incurred by the candidates. The candidate component is not fully documented but a baseline number would be the Rs. 5.5 million expenses disclosed by Ranjan Ramanayake who contested in the Gampaha District multiplied by the number of candidates which would have been more than 15,000. That would yield a total in the range of Rs. 75 billion.

Short of going back to the pure Westminster model, there are two possible solutions. One is to elect the President through an electoral college comprising members of the legislatures representing the national as a whole and the provinces as is done in countries like Myanmar which have powerful Presidents. The other is to hold the Presidential and Parliamentary elections on the same day as is done in the United States.

But this was not the element of the 1978 Constitution that was removed by the 19th Amendment and which is sought to be restored. It is the power of the President to dissolve Parliament after one year from the General Election. If the two mandates are independent of each other, it made no sense to allow the single person serving as President to arbitrarily dissolve Parliament after the expiration of only one-sixth of the mandated term and nullify the mandates of 225 Members of Parliament.

Following the abuse of this problematic authority by President Kumaratunga in 2004, it made eminent sense to amend the relevant Constitutional provision. And so, it was amended through the 19th Amendment which was approved with only one dissenting vote in 2015. There are many ways by which the term of a Parliament may be ended under the Constitution. The whim of the President remains as one. But it can now be exercised only after the passing of four and a half years of a five-year term, or after the expiration of 90% of the mandate.

Now the legislature can exercise the legislative power of the people without fear of premature dissolution. Checks and balances cannot be effective when one of the parties can arbitrarily terminate the existence of the other at any time after a year. The Parliament does have the power to impeach the President, but this requires a complex procedure. Constraining the power to dissolve Parliament is an eminently sensible improvement to JR’s Constitution.

Limits on Cabinet size

Another mistake in the 1978 Constitution was the absence of a Cabinet size cap. There is widespread opposition among the people to gargantuan Cabinets. In the oldest Constitutional democracy, the United States, the Departments (as Ministries are described there) are fixed in number and name. Congressional approval is required to create a new Ministry. The need to limit the number of Ministries was recognised even while JR was President. But this limit was applied only to the Provincial governments, not the centre.

The 19th Amendment provided an imperfect solution, but it was an advance, nevertheless. It does not specify the Ministries, but imposes a cap of 30. The number of non-Cabinet Ministers and Deputy Ministers is also capped at 40. It allows for a loophole for national governments (undefined) where Cabinet size can be set by Parliament. Illogical Ministries may still be created, but their number is limited.

What needs to be done is to close the loophole by carefully defining what a national government is, or by removing any exceptions to the limit of 30. The real improvement would be to define the Ministries by name and prevent the creation of illogical or comical Ministries for the sake of political expediency.

Independent commissions

In his comments on what is to be preserved from the 19th Amendment, the eminence grise Basil Rajapaksa did not mention independent commissions. Given the demonstration of the value of independent commissions by the performance of the Elections Commission, it is unlikely that reversion to an Elections Department will be proposed.

What is likely is a reversion to the fig-leaf appointment procedures of the 18th Amendment. This is what allowed the then President to ask one of his Law College friends to drop in at Temple Trees on the way home and offer her an appointment as a Judge of the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka.

If the necessary conditions of true independence are to be preserved, a collegial body such as the current Constitutional Council must be entrusted with shared responsibility for important appointments. It is only if the members of the Independent Commissions are appointed properly and they cannot be removed easily that they are likely to perform their duties without fear or favour.

Some will point to the performance of the Police Commission as evidence of the failure of independent commissions. It takes time for the right culture to be established. The procedures and laws are only the necessary conditions for effective exercise of authority by independent commissions. The sufficient condition is the actions of those entrusted with authority.

Simply because former Chief Justice Sarath Nanda Silva issued unjust judgments and sullied the judiciary, one does not propose the removal of safeguards for the independence of judges, including proper procedures for their removal. In the same way, the Constitutional Council created by the 19th Amendment should not be replaced with a fig-leaf commission that will allow a single human being with a limited mandate to make judicial and other important appointments as it was possible under the unlamented 18th Amendment.

Why the rush?

Irrespective of party affiliation, anyone with the interest of the country at heart can support the preservation of the above elements of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution. These were needed changes which remedied obvious flaws in the 1978 Constitution. There is no reason to go back to what did not work. There are more important things the government can focus on, especially given the massive majority in Parliament and the challenges posed by a contracting economy and debt repayments coming due. Why repeat the error of rushing through the 18th Amendment in 2010 after another massive electoral victory?