Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Thursday, 16 November 2017 00:52 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

On the invitation of an old friend, I had the opportunity of visiting Seychelles. My friend, a senior officer in the Government Service,has received official accommodation in the mountainous region and accommodated my family in his residence.

Looking out from the bedroom balcony, I noticed a large tree covered with tiny flower buds in the adjoining property, the tree around 30 feet tall, covering nearly seven to eight perches. The tree looked familiar and I identified the tree as cinnamon, for I had few cinnamon trees in my garden. I also noticed many other cinnamon trees in the vicinity, along with few coconut trees, some with fallen coconuts lying on the ground. I learnt there is no cinnamon industry in the country; also coconuts are not consumed, thus not picked.

Republic of Seychelles

Seychelles is one of the most beautiful islands in the world. The nation with 115 islands spread over 800sqkms in the Indian Ocean, lies 1,500km east of East Africa and to northeast of Madagascar, is only four flying hours from Colombo.

The country’s islands consist of granite mountains jutting out of the sea and coral atolls. The first group has 42 islands, with a total area of 244km2. The largest island Mahe, hosting capital Victoria, is a granite hill rising over 900m, is only 10km wide and 45km long.

History

The islands was a transit point of trade between Africa and Asia, occasionally used by pirates. In 1778, French made a formal claim for the islands and French planters settled with their slaves. But French were forced to hand over Seychelles to British under the ‘Treaty of Paris’ in 1814, but the treaty allowed French to retain their land. During the 19th century, Chinese and Indian tradesmen, together with former slaves settled in the island engaging in agriculture. Seychelles became a British crown colony in 1903 separating from Mauritius. The country gained independence in 1976 and is a member of the Commonwealth.

Although the British prohibited slavery in 1835, African workers continued to be used and cinnamon, vanilla and copra were the chief exports. The plantation based economy continued until independence and employed a third of the working population. Currently, around 5,000 Sri Lankans are employed in Seychelles, mostly in hotels, also around 10,000 Indians mostly in trading.

Today, plantations are no more, except for a small tea plantation run by a Sri Lankan manager producing organic tea. Cinnamon plantations are found in Mahe, Praslin and Sihouette islands. Vanilla plantations have perished due to disease. In abandoned cinnamon cultivations overgrown trees flowered, birds spread seeds over the island, also to other islands, is considered an invasive species and a threat to indigenous plants.

Environment

The Seychelles Government is extremely conscious of environment and legislation is very strict, tourism projects must undergo an environmental review and a lengthy process of consultations with the public and conservationists.

The majority of the 115 islands are uninhabited, with many dedicated as nature reserves. The country is 89% under forest andholds a record for the highest percentage (50%) of land under natural conservation. The grounds are extremely fertile, there is no wildlife and no snakes, only birds. The country has prohibited polythene long ago, the Government collects all refuse and does not allow burning even the fallen leaves.

The majority of the 115 islands are uninhabited, with many dedicated as nature reserves. The country is 89% under forest andholds a record for the highest percentage (50%) of land under natural conservation. The grounds are extremely fertile, there is no wildlife and no snakes, only birds. The country has prohibited polythene long ago, the Government collects all refuse and does not allow burning even the fallen leaves.

Of the 115 islands 42 granite are hilly, the balance are coral atolls, many small islands of both categories are uninhabited. Some are reserved for birds (Bird Island,etc). Aldabra Atoll is home to some 100,000 indigenous giant tortoises, some weigh over 400kg and live up to 120 years, the uninhabited Aldabra coral atoll is a World Heritage Site.

Economy

The country’s economy depends mostly on tourism and fisheries for foreign exchange. Seychelles islands spread over Indian Ocean command territorial waters of 1.3 million km2. Tuna fishing is the highest earner with licencing fees paid by foreign companiesthat trawl in Seychelles waters.

In employment, around 1,500 locals are employed in active fishing and nearly 3,000 employed in the tuna canning factory claimed as the world’s second largest. A couple of years ago, around 120 Sri Lankans were employed in the factory. After a few months the meals provided did not agree with them and they went on a sit-down strike. The next day the entire lot was deported.

Social

Most locals are a hybrid of Africans and French. Official languages are French and English along with Seychelles Creole, primarily based upon French. The government provides housing for the citizens and there are no shanties. The minimum wage is around SRS 7,000 per month or around Rs. 75,000.

The State provides a dole for unemployed, increasing with children numbers. The children are registered under the mother and registration of marriages are few. Most males are lazy, indulging in drinking and drugs. Fisheries has made Seychelles a hub of drug distribution. Every shop sells items including liquor. The cost of food and groceries are generally on par or below current Sri Lankan prices, liquor is much lower.

The State provides a dole for unemployed, increasing with children numbers. The children are registered under the mother and registration of marriages are few. Most males are lazy, indulging in drinking and drugs. Fisheries has made Seychelles a hub of drug distribution. Every shop sells items including liquor. The cost of food and groceries are generally on par or below current Sri Lankan prices, liquor is much lower.

The country has a population of 95,000 and around 30,000 vehicles. Drivers are extremely courteous, giving way to others and sounding a horn is unheard. My friend’s four-year-old official vehicle had done only 13,000kms; on a small island, where can one go?

Agriculture

Today, agriculture employs only 2% of employable, but at independence in 1976, employed almost 35% and exported cinnamon, vanilla and copra. With the opening of the International Airport in 1971, job opportunities opened up in construction and hotels, offering higher salaries. With limited workforce, agriculture suffered. Today, cinnamon is considered an invasive species threatening local indigenous plants. Thus, the Government in spite of their strict respect for vegetation would permit harvesting of cinnamon.

Opportunity of recommencing cinnamon industry

With the above status, it should be possible and financially feasible to have a cinnamon-based industry in Seychelles, especially as available trees could be harvested, without having to cultivate, only harvesting and processing of plants, the most positive factor being the cinnamon variety in Seychelles is the same as the Sri Lankan variety.

The commencement of a project would involve a project feasibility report, environment study and acceptance by the Government. In harvesting of existing plants avoiding soil erosion is essential. With harvesting new shoots would sprout from the stumps creating a sustaining industry. Once harvested, the tree trunks, branches and leaves would have to be transported to the processing centre. In addition, the process all waste need be made use and consumed. As local labour is in short supply, the industry will need to use labour from Sri Lanka.

In Seychelles, availability of oversized tree trunks, large and small twisted branches with lots of leaves, production of cinnamon quills would not be possible. Barks from mature branches be more suited for bark oil and leaves for oil.

Cinnamon industry in Sri Lanka

The Sri Lankan cinnamon industry is based on harvesting cultivated shoots, peeling the shoots producing cinnamon quills 42 inches long. In addition, cinnamon leaf oil from leaves and bark oil from the barks command a higher market value, but are manufactured by few.

Cinnamon bark and leaf oils are produced by steam distillation of the bark or leaves, but the industry is losing the market share due to failure in development of machinery and techniques.

Among the Lankan entrepreneurs, Knight Manufacturing, Ambalangodadeveloped a cinnamon peeling machine; Davora Ltd. claims rehabilitating a cinnamon bark oil distillation plant in Kamburupitiya, with the Industrial Technology Institute (ITI). A number of institutions have improved their own machinery for oil extraction, but details are unavailable. The Government had neglected the industry and even the locally produced peeling machines are not popularised, while experiencing a labour shortage in the industry.

Institutions such as the Cinnamon Research Station, Kamburupitiya under the Department of Export Agriculture are confined to development of cinnamon cultivation, pest control and recovery of peel. The National Cinnamon Training Academy, Matara concentrates on training of peelers, as peeling is carried out under unhygienic conditions. In addition, the Cinnamon Training Academy was inaugurated in Kosgoda in 2016 as a public-private partnership between UNIDO and WTO in cooperation with the Spice Council of Sri Lanka. But their contribution to the advancement of technology is unknown. Meanwhile, Sri Lanka has been gradually losing its market share in the international market.

Past attempt to revamp cinnamon in Seychelles

At the request of the Seychelles Ministry of National Development, the US Agency for International Development carried out a technical feasibility in 1983 for re-establishing cinnamon leaf distillation. The report is available at http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNAAQ104.pdf.

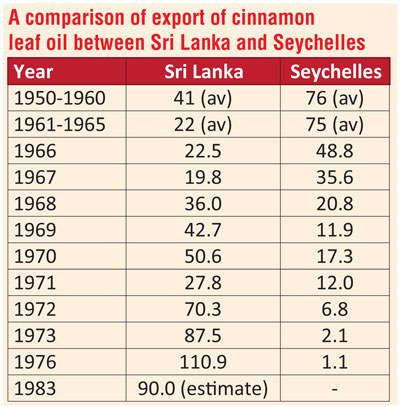

The Agency examined the technical feasibility of re-establishing cinnamon leaf distillation in that country. Cinnamon bark and cinnamon leaf oil exports made large foreign exchange earnings, the reduction in production has had a serious effect on the agricultural economy. Production of cinnamon leaf oil between 1950 and 1965 in Seychelles was around 75 metric tons, or about 70% of total world production. Extracts from the report are given below.

Background

Cinnamon was introduced into the Seychelles in 1772. By the late 19th century it had completely dominated the secondary forest vegetation, and even volunteered in coconut groves. The reason for this great dispersal was because the fruits were a popular source of food for the indigenous fruit pigeon (Dutch Pigeon or Hollandaise) and the Indian Mynah bird (AcridotheresTristis). For the most part, the trees were left alone to multiply and spread. By the mid 1950s cinnamon had spread all over the islands of Mahe, Silhouette, Praslin and La Digue.

Cinnamon bark was first exported on a very limited scale in the early 19th century. In addition, a small distillery was in existence at Cascade (Mahe) before 1900. By the mid 1960s, approximately 1,500 tons of bark and 50 tons of leaf oil were exported annually.

Present situation

After Seychelles gained independence in 1976, there was a lull in the production of both leaf oil and bark. By 1982, only 419 tons of bark were exported while cinnamon leaf oil was not produced.

The opening of international airport on Mahe in 1971 changed the whole economy of the Seychelles. Earlier, cinnamon and copra had been the major exports generating foreign exchange. With the airport in place, the development of tourist industry and influx of foreign investment capital began to change the economy of this island community.

Tourists require hotels, restaurants and bars, so the early ’70s saw a development of local construction industry. This industry needed a large amount of unskilled and semi-skilled labour, so the men who traditionally worked in the copra and cinnamon harvests were lured away from the agricultural sector by higher wages.

Cinnamon in Seychelles

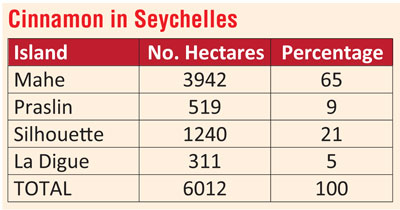

It was estimated by the late 1960s that there were approximately 6,000 hectares of cinnamon growing in the wild state on Mahe, Praslin, Silhouette and La Digue.

It was estimated in the mid-1970s that the area under cinnamon had increased to 8,100 hectares. It is assumed that because of the lull in the industry there are approximately 10,000 hectares of cinnamon growing in a wild state.

Conclusion

1) The reintroduction of Seychelles cinnamon leaf oil into the international market would be an unsound investment because of price restrictions and market constraints,

2) Seychelles would have to be re-established as a reliable producer of cinnamon bark before an oil processing industry could be considered, and

3) If the decision is made to re-enter the world market with Seychelles cinnamon leaf oil, it would have to be heavily subsidised.

End of extracts.

Possibility of Sri Lankan investment in Seychelles

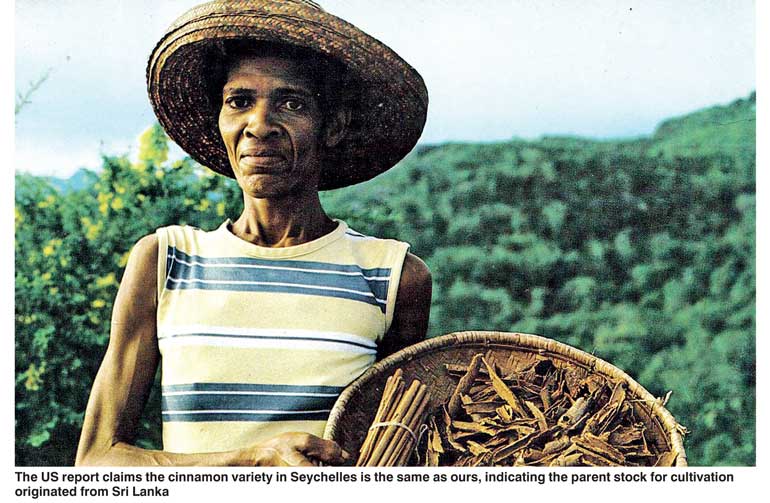

The US report claims the cinnamon variety in Seychelles is the same as ours, indicating the parent stock for cultivation originated from Sri Lanka, but the industry collapsed due to labour shortage. Sri Lanka has 25,000Ha under cinnamon and in 1960 Seychelles had 6,000Ha, today due to invasive nature the coverage would be more. Thus Seychelles has sufficient acreage to sustain a substantial cinnamon industry, by harvesting existing plants. But plants are overgrown, peeling would be difficult and production of quills would not be possible. Thus production would be bark and leaf oil, as carried out earlier.

The current minimum wage in Seychelles is approximately Rs. 75,000 per month, also in short supply and the investor will have to use Sri Lankan labour. Labour intensive methods will not be feasible and mechanisation is necessary. Above shows until 1976 Seychelles has exported more leaf and bark oil than Sri Lanka. Our production techniques are ancient and will require modern and efficient extraction methods.

Another challenge is the disposal of leftovers from the manufacturing process, considering Seychelles is extremely conscious of environment. Thus, waste leaf after extraction of oil and cinnamon wood after peeling of bark need to be utilised or presented in a usable manner. In large tree trunks some recovery of timber could be possible, but off-cuts and branches would be a problem.

A local company, Don’s Renewables (https://donsrenewables.lk), converts sawdust and timber offcuts to conveniently-handled fuel for feeding boilers and furnaces. Almost every hotel in Seychelles carries out barbeques and would require charcoal. But whether the cinnamon leaves after oil extraction could be compacted into fuel to run boilers that extract oil is to be investigated.

Government assistance

Sri Lankan cinnamon has earned a reputation of undisputed quality for centuries and is referred to as real cinnamon. However, the industry has done little to advance, meanwhile other countries have bypassed us. The Government needs to take immediate steps to advance the industry from age-old habits with modern technology, especially in production of bark and leaf oil as well as usage of wood and leaf now burnt or thrown away damaging the environment.

The Government of Seychelles’ policy of productive use of existing invasive cinnamon plants, affecting local plant species, needs to be presented and accepted, best presented by the Sri Lankan Government and implemented by the private sector. Acceptance would not be difficult due to Sri Lanka’s reputation as the best cinnamon in the world and also given the cordial relations between the two countries.

The venture requires getting together a producer of cinnamon oils, a machinery manufacturer and a converter of waste into usable fuel. In addition, research organisations need to get together to develop advanced machinery that could be used by the local industry. The initial development costs will have be borne by the State.

Localentrepreneurs venturing into Seychelles to reactivate their cinnamon industry would help to improve our technical competence, improve relations between two countries, provide employment to locals and companies would earn a profit, a win-win situation. But the venture cannot take off without Government support and initiative.