Friday Feb 27, 2026

Friday Feb 27, 2026

Wednesday, 1 November 2017 00:16 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Advocata Institute

By Advocata Institute

State Minister for Finance Eran Wickramaratne’s comments that the Government will cut red tape in issuing visas to fill critical skill gaps is a welcome development as it will help Sri Lankan businesses grow faster, win bigger contracts and employ more people.

Shortages are apparent in several sectors as Sri Lanka’s labour market with unemployment falling to 4.4% in 2016 from 6.5% in 2006. Tourism, agriculture and construction sectors are among those complaining. The leisure sector not only needs well-trained workers until domestic training catches up, but also specialists with Chinese language and cooking skills to cater to a sudden influx of tourists from China.

Firms in Information technology and business process outsourcing (IT/BPO) sector are also finding it difficult to get specialist workers in particular.

The difficulty in getting specialist skills has stifled an entire eco-system of small, medium and start-up companies that are emerging, preventing them from winning bigger contracts and growing faster. A growing information technology sector, where more small companies expand rapidly, or which drawn outside investments, can also help retain some of the most talented IT professionals who are now migrating due to lack of upward career growth.

The tech entrepreneurs who are complaining of skills shortages are also IT professionals.

The proposal to streamline the process of sourcing labour from overseas has triggered a protest from one group of information technology workers.

Though it is understandable that these workers fear that they may lose jobs, IT workers-turned SME entrepreneurs say there is not enough awareness in the country about the dynamics of the market, which are fast changing and how cutting red tape will bring benefits for everyone including workers themselves.

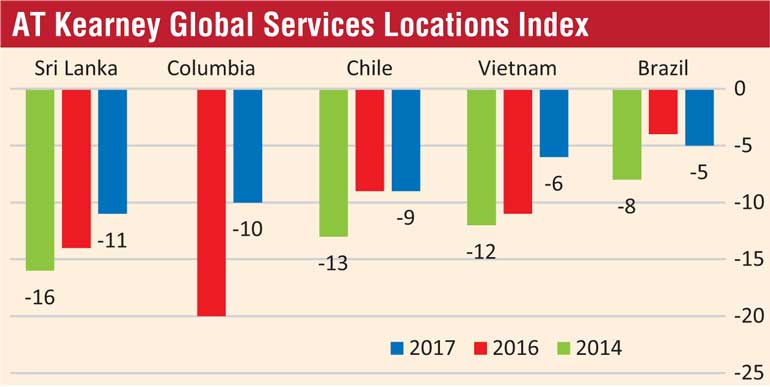

Those chasing short term gains and protection, will not only deny an opportunity for Sri Lanka to grow, but may also hurt themselves in the long term, by denying opportunities for career growth. Meanwhile other countries are not standing still. Countries like Vietnam, which are more open in multiple ways, is already ahead of Sri Lanka in the BPO game, is overtaking others.

Past experience has shown that clearing bottlenecks and removing roadblocks can unleash growth and employment.

Sri Lanka’s IT service sector got a firmer foothold in the global market 1990s when the then telecom minister broke a monopoly held by Sri Lanka Telecom by introducing competition. An international voice and data monopoly was broken a few years later, ending another protection afforded to SLT, cutting costs and making the IT sector competitive.

Though Sri Lanka Telecom lost market share, its business is now part of a bigger pie and the firm is better positioned deal with competition from services such as Viber and WhatsApp. The entire country also has access to cheaper telephony and faster data services. Many people have found work in businesses connected to the telecom sector.

The fee levying Sri Lanka Institute of Information Technology (SLIIT) was also set up in the late 1990s, partly with the intermediation of the Board of Investment, giving economic freedoms to many students who would otherwise have been hurt by a road block in the form of a tax-payer funded state monopoly in IT degrees.

At the time there was no Government IT Officers Association, like in the medical sector or any such body to prevent these freedoms from being given to the students and the country, after resistance from Sri Lanka Telecom was dealt with.

It is therefore important to understand the issues and dynamics at play in the software and information technology market, particularly in the small, medium and start-up sector, and why tech entrepreneurs want foreign specialists to grow faster.

The Sri Lanka Association of Software and Service Companies (SLASSCOM) says about 3,000 students qualify from State universities each year. Reliable estimates are unavailable of private sector output or migration. The best graduates are snapped up by the largest players. Some are also absorbed by firms catering to the domestic market. Some qualify in hardware and networking areas.

But it is a fact that large companies like Google and Microsoft who employ a 1,000 or more workers in a location are not coming to Sri Lanka. The IT/BPO industry is estimated to employ around 80,000 people of various disciplines. Understandably existing industry players may also be comfortable with this situation as the entry of any big name can lead to poaching and a steep rise in wages.

The problem of attracting large tech companies who need a large volume of labour is one side of the coin. The lack of specialist skills is another one.

Given that Sri Lanka is a small market students tend to go on a more general route. It may not make economic sense to go for additional qualifications especially when it is quite easy to get a well-paid job with expertise in general areas.

But the industry is changing fast and new skills are needed. At one time a programming language like Python may be ‘hot’. At another time there may a shortfall of good User Interface and User Experience (UI/UX) specialists, who will design and build the front end of an application so that users can do their work easily and with as less training as possible.

Industry watchers say there is a trend where entrepreneurial software engineers with several years of experience under their belt, are setting up small outfits to cater to the international market. They have know-how, some management skills and customer relationships to work with foreign clients.

For a small company, getting the right mix of specialist skills is not easy, especially when requirements change rapidly.

For example a Sri Lankan SME bidding for a contract in Europe may require a 30 software engineers, but the client askes for five certified usability testers. Another deal may require five qualified data scientists. The company may have 25 staff, but lack the five specialists. They will have to give up the job, when specialists are not available even if the client firm is willing to engage them.

Sometimes such talent may be available from a larger company, but poaching them at high prices may make the bid unviable. Due to the lack of specialist skills, many SME founders say they are now hitting a roadblock.

IT entrepreneur say that Indian or Filipino developers are not necessarily cheaper to employ than Sri Lankans, with living costs in Sri Lanka being higher than in countries like India.

A fast-growing industry will also help reduce the migration of seasoned professionals, which is a big problem dogging the industry.

Currently IT professionals who gain experience and reach lower management level find that there is not enough opportunities for career growth due to the slow expansion of the industry.

By the time a tech professional gains mid-level experience, the salary gap between Sri Lanka and other markets widens. With limited options at home, these professionals migrate.

If the industry grows faster, more experienced IT professionals will remain in the country. By opposing measures that may make an industry grow faster a section of IT workers may be denying themselves and their colleagues’ opportunities for career growth.

As it happened with products exports, there are fears that Sri Lanka is lagging behind, though the country may have been a pioneer in removing the first state controls.

In the Global Services Locations Index compiled by AT Kearney, Vietnam was ranked 19th in the world in 2007, with a People Skills and Availability score of 0.99 points. Sri Lanka was only slightly behind with a score of 0.96.By 2017, Vietnam had moved to 06th place, overtaking the Philippines. Vietnam had radically improved its score in People Skills and Availability to 1.39. Sri Lanka’s score in the People Skills and Availability sub-index had only improved to 1.07 points.

Philippines had been a leader in East Asia due to its English ability. Vietnam had an early start serving the Japanese market but big Western firms are now moving in.AT Kearney noted that a “significant percentage of the predominantly young Vietnamese population is now fluent in English”.

Young Vietnamese are learning English quickly due to a booming formal and informal private education system staffed with teachers from the US, UK and Australia who are moving to the country easily.

The start-up boom and the wide adoption of software in the local market offers hope. But it can be realised by being open to investment and talent.

When more Sri Lankans work with specialists, they will also acquire some of the know-how as knowledge diffusion occurs faster when people move.

SLASSCOM, the industry body, has recommended that a program be launched to attract diaspora and international knowledge workers, a non-resident type dual citizen scheme be introduced and easier visa and work-permit process for knowledge workers similar to an existing program to attract regional headquarters of global companies to Sri Lanka be offered.

Sri Lanka should not just think about clearing red tape for easier sourcing of specialist skills as the Government plans, but move beyond and think about a structured skilled visa programme along the lines of other countries that are technology hubs.

Other countries are moving even further. Thailand recently announced a four year ‘smart visa’ for business professionals without the need for a work permit.

Sri Lanka plans to be a service hub for the Indian Ocean. These lofty goals cannot be reached without quick access to knowledge workers who will in turn impart their knowledge to Sri Lankans.