Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday, 7 August 2019 00:30 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

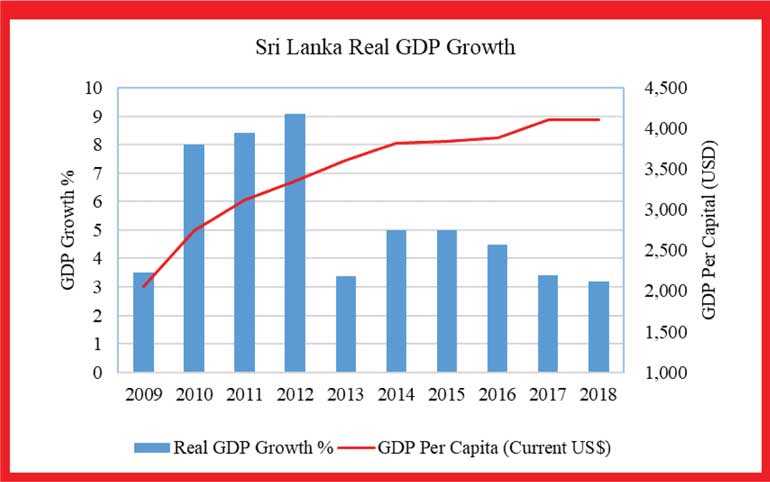

The Sri Lankan economy grew at an annual average rate of 5.4% over the past 10 years from 2009 to 2018. The country reached a milestone in its economic progress with the graduation to an upper middle-income economy in July 2019. This is an opportune time to reflect on the journey ahead and put in place a plan to make further progress towards a high income country.

Recent growth episodes

In the five-year period from 2009 to 2013, which was the period immediately after the end of the 26-year civil war, the economy grew at an annual average rate of 6.5%. The higher growth was particularly impressive in the three years after the end of the war. GDP growth was 8.0% in 2010, 8.4% in 2011, and 9.1% in 2012, showing a continued high growth trajectory.

However, this momentum broke with growth declining substantially to 3.4% in 2013. During the last five-year period from 2014 to 2018, the average annual growth declined to 4.2%. This is a more than two percentage point drop relative to the previous five-year period. Moreover, growth has continued to moderate since 2015 ending with a 3.2% growth in 2018, the lowest in 16 years. Due to the economic impact of the Easter Sunday attacks in April 2019, growth is expected to be 3% or lower this year.

Per capita GDP

Sri Lanka’s nominal GDP per capita recorded an increase from Rs. 465,976 in 2013 to Rs. 666,817 in 2018. Accordingly, the annual average increase in GDP per capita over the past five years is 7.4%. In dollar terms, the GDP per capita increased by 493 dollars from 3,609 to 4,102 in the same period. The annual increase in dollar terms is only 2.6% due to the depreciation of the rupee at an annual average rate of 4.7%.

Now an upper middle income economy

Sri Lanka reached an economic milestone in July 2019, when the World Bank classified the country as an upper middle income economy. The World Bank’s classification of countries into income groups is based on the Gross National Income (GNI) which measures all the income of residents and businesses including net foreign factor income.

The GNI threshold to become an upper middle-income country in the 2019 is 3,996 dollars and Sri Lanka’s GNI for 2018 of 4,060 exceeded this threshold. As a result, we are now in an exclusive club which includes China, Malaysia and Thailand. Of course, it is important to realise that these are much larger economies. Relative to size of the Sri Lankan economy of 89 billion dollars last year, China recorded a GDP of 13.6 trillion dollars, Thailand was 505 billion dollars while the Malaysian economy reached 354 billion dollars. On a per capita basis, the GNI was $10,460 in Malaysia, $9,470 in China, and $6,610 in Thailand.

Aspiring to become a high income economy

The next level of income category is high income for which the threshold is 12,376 dollars currently. This means, Sri Lanka’s GNI has to increase threefold to reach a high income economy. High income economies in Asia include Hong Kong, Singapore, Korea and Taiwan, among others.

What would take Sri Lanka to reach high income status? Evidence suggests that the median number of years it took a country to transition from upper middle income to high income has been about 15 years. Both China and Thailand have been upper middle income countries for 10 years since attaining upper middle status in 2010. Malaysia has been in the upper middle income category for 25 years since 1994. At current economic growth rates, the World Bank has indicated that Malaysia could achieve high income status by 2024. Then, it would have taken Malaysia 30 years to transition to a high income economy.

The time it takes to reach high income depends on the future economic growth rates, exchange rate, inflation rate and population growth.

Assuming an annual average population growth rate of 0.5%, inflation of 5%, and rupee depreciation of 3%, with a real economic growth rate of 6% a year Sri Lanka could reach the level of GNI per capita of approximately 8,000 dollars in 10 years (by 2029) and 12,000 dollars in 15 years (by 2034).

On the other hand, a lower growth path of 5% per year, higher inflation at 6%, higher rupee depreciation of 4%, and higher population growth of 1% will increase the transition time to a high income economy to 20 years.

The road to high income is challenging. But Sri Lanka has the potential to achieve high single digit growth with a long-term, integrated national socio-economic development policy framework aimed at increasing the rate of investment and productivity of labour and capital.

(Professor Lalith Samarakoon is a Financial Economist and serves as the Secretary-General and Chief Economist of the National Economic Council of Sri Lanka. Follow Perspective at www.lalithsamarakoon.com and Twitter @LSamarakoon. Email at [email protected].)