Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Tuesday, 25 September 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

During 2011/12, the then administration of the Central Bank had spent $ 4.2 billion out of its reserves in a desperate bid to defend the rupee. Yet, it could not prevent the depreciation of the rupee by 13.5%. Similarly, in 2015, under the present Government, the Bank had spent $ 1.2 billion to protect the rupee only to experience a depreciation of the rupee by 9%. Sri Lanka today is in the same critical situation

Not all are losing when the rupee depreciates

The recent depreciation of the rupee against the US dollar in the market has apparently driven the entire nation to a panic mode. While it had been a field day for the media and opposition law makers, the public, made up of both gainers and losers when the rupee depreciates, have temporarily forgotten the gains and chosen to be driven by the sentiments of losing.

For instance, those in the export of goods and services and those who send remittances back to Sri Lanka stand to gain when they get more rupees for every dollar they earn or remit. But those who consume imported products and those who plan to avail themselves of foreign services like travel abroad, education or healthcare services will lose since they have to now spend more rupees to buy dollars.

The Government is a net beneficiary of depreciation

The Government on the other hand, as I have pointed out in my previous article titled ‘Rupee’s sad destiny of one way journey to depreciation’ (available at: http://www.ft.lk/columns/Rupee-s-sad-destiny-of-one-way-journey-to-depreciation/4-654254), is a net gainer in this depreciation game. That is because though it has to find more rupees to finance the current year’s external debt servicing, it earns more rupees by way of higher import duties when imports are valued at a depreciated currency and when it borrows in foreign exchange and sells those dollars to the Central Bank.

For instance, in 2018, if the exchange rate depreciates by one rupee per dollar, the Government is to earn an additional amount of Rs. 4.5 billion, more than double the increase of Rs. 1.7 billion by way of servicing the external debt. Of course, this is not a valid reason for a Government to allow its currency to depreciate in the market. That should happen, as is the case of Sri Lanka at present, when the fundamentals in the foreign sector are at odd, namely, when the country fails to earn enough foreign exchange to meet foreign exchange payments year after year. To address that issue, economic policy makers in the Government should have a different set of policies.

Panic causes to choose the worse data

The reference exchange which panic-makers have used had been the average selling rate of dollars by banks when they do transactions among themselves in what is known as the interbank spot foreign exchange market. The rate published by the Central Bank in this connection had been the actual average transaction rate pertaining to the previous day’s business (available at: https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/rates-and-indicators/exchange-rates). However, commercial banks quote in this market not only a selling rate but also a buying rate which is about Rs. 4 lower than the selling rate.

The Central Bank which compiles the data publishes both the buying and selling rates and also an indicative rate which is the mid rate between them. For all purposes, the Bank and other agencies like the Customs use this indicative rate. According to Central Bank data, as on 21 September 2018, commercial banks had offered to buy dollars for Rs. 166.78 per dollar and sell them for Rs. 170.66. Accordingly, the underlying indicative rate had been Rs. 168.03 per dollar. However, since the selling rate had been higher, the movement in that rate had been used to drive panic into the heads of the public.

Devaluing the rupee through the FEEC system

Since independence till 1968, Sri Lanka had a single fixed exchange rate at Rs. 4.76 per US dollar. As the country did not have sufficient foreign exchange balances to maintain this fixed exchange rate, the rupee was under constant pressure for downward rate adjustment which was called ‘devaluation’ in that fixed exchange rate system.

By 1966 when the problem became chronic as well as acute, Sri Lanka decided to go for a dual exchange rate system instead of fully devaluing the rupee. In this dual exchange rate system, the essential imports were at the official exchange rate. All others were at a premium of 65% above the official rate under a system called Foreign Exchange Entitlement Certificate or FEEC system. It was equivalent to levying of a tax of 65% on users of foreign exchange.

Since a greater part of imports were at the FEEC system, it was a lucrative revenue source for the Government. As such Dr. N.M. Perera who as an opposition member had accused the Government of being a black market foreign exchange seller under the FEEC system did not see the necessity for its abolition after he became the Minister of Finance in 1970.

This practice of partial devaluation was continued till 1977 when it was abolished under the new flexible exchange rate system introduced by the Government. Under this system, the rate was unified at Rs. 15.56 per dollar representing an effective devaluation of 7% over the FEEC rate.

Under the flexible exchange rate system, the value of the rupee against the dollar was allowed to be determined in the market. Accordingly, any decline in the value was called ‘depreciation’ as against ‘devaluation’ in the previous fixed exchange rate system. Similarly, any increase in the value was termed ‘appreciation’ as against ‘revaluation’ in the fixed exchange rate system.

Blame-excuse game played by politicians

Since then what Sri Lanka has experienced has been a continuous decline in the value of the rupee. It had been the practice of politicians in the opposition to charge the government in power for failing to maintain the value of the rupee. Those in power had been defending their position blaming outside forces for the sad fate of the currency. However, since no action is being taken to remove the fundamental causes for the depreciation of the rupee, it continues its sad one way journey to depreciation. As such, when the political power changes hand, the blame-excuse game is now played by the very same politicians who now play the opposing roles.

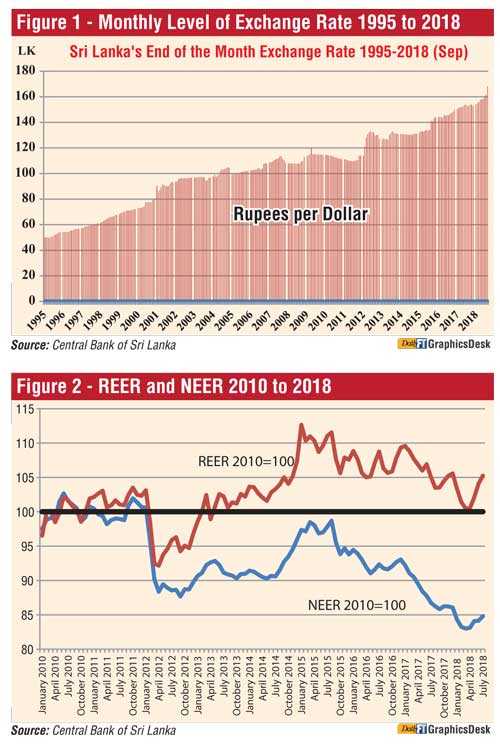

Figure 1 shows the decline in the value of the rupee against the US dollar from 1995 to mid September 2018. As the graph demonstrates, it is a continuous depreciation with some bumps in certain periods. It is therefore important to indentify the causes for the rupee to depreciate in the market continuously in this manner.

Avoiding a deficit in the current account

If a country is interested in stabilising the value of its currency, there is only one recipe for it. That is, it has to earn sufficient amount of foreign currencies to meet the demand for foreign currencies from its own citizens.

Foreign currencies are earned by countries by selling goods, known as exports, selling services and selling factor services to foreigners. These are being topped-up by a non-selling foreign exchange flow, called inward transfers, which a country gets by way of gifts. In banking parlance, they are known as remittances by Sri Lankan workers abroad.

On the other side, Sri Lankans demand for foreign currencies to import goods, buy services from outside and pay for factor services like paying interest on loans and profits for investments. To these payments are added the gifts which Sri Lankans extend to foreigners, known as outward transfers.

These transactions could be amalgamated into an account called the current account of the balance of payments by recording the first category on the credit side and the latter on the debit side. The essential requirement for a currency to be stable is that this current account should be balanced or if it has deficits, those deficits should be offset by similar surpluses in other years. If there are continuous surpluses, the country earns more foreign currency than it needs.

Unless those surpluses are lent to other countries, the country may experience a continuous appreciation of its currency. If there are continuous deficits, it has a shortage of foreign currencies. These shortages have to be filled by borrowing from other countries and it would help the country to temporarily stabilise its currency. But it would add to its foreign debt driving it to a malady known as debt trap. It makes the matters worse and the country is, therefore, destined to experience a one-way journey toward depreciation of its currency.

Sri Lanka’s dismal track record in the current account

This latter situation is the one which Sri Lanka has experienced during the entirety of the period since 1977. Its current account has been in deficit and, when measured as a percent of the size of the economy or GDP. That deficit, though low at about 2% of GDP today, has been as high as 16% in early 1980s.

When the current account deficit goes up, the country is in the habit of pressing the panic –button talking about the necessity for introducing the needed external sector reforms. But on the other side, when it goes down even by a small magnitude, it falls into a state of complacency, ignoring the risk and danger it is facing.

During the period from 2012 to 2017, the current account deficit has been on average at 3% of GDP a year. Therefore, there has been pressure for Sri Lanka rupee to depreciate. What the previous administration did was to borrow abroad and use the proceeds to release the pressure in the market. It is like giving some pain killer to a cancer patient to relieve of his pain. It is not a cure. Hence, the wound begins to fester within the body without proper medication. One day when the cancer becomes acute and it is too late to administer any medication, the patient would succumb to his illness.

The inactivity of the new Government

This was known at the time when the new Government took power in January 2015. But the Central Bank’s Monetary Board as well as the Minister of Finance behaved as if there was no economic crisis.

The Central Bank Annual Report for 2014, released in April 2015 under the stewardship of the new Government, talked complacently about the stability of the rupee during 2014. That was against the US Dollar. It had been more complacent when it had reported that the rupee has appreciated on average against the currencies of its major trading partners during 2014.

Nominal and real effective exchange rates

To assess this average change in the value of rupee against its trading partner currencies, the Central Bank calculates two effective exchange rate indices, one for rupee’s nominal value and the other for its real value. The fact that both these indices have appreciated in 2014 means that Sri Lanka has lost its competitiveness against exports and gained a preferential advantage for its imports. This is an ailment because it suppresses exports and encourages imports, the main cause for the rupee to come under pressure for depreciation in the long run.

Financing the foreign exchange shortage by continued borrowing

Figure 2 shows the movement of the real effective exchange rate (REER) of Sri Lanka as against the movement of the nominal effective exchange rate (NEER) during 2010 to July 2018. It is seen that till January 2012, both indices have moved comfortably side by side to each other. However, since then, REER had been continuously appreciating while NEER had remained below 100 throughout.

An appreciated REER will erode the competitiveness of Sri Lanka’s exports thereby acting as a tax on the export earnings and a subsidy on imports. Both have caused the widening of the country’s trade deficit from $ 9.4 billion in 2012 to an estimated deficit of $ 11 billion in 2018. Since the remittances which are the main financing source of the trade deficit have been stagnating at around $ 7 billion, it has resulted in a current account deficit of around $ 3 billion that has to be financed by borrowing from abroad. This is the tactic used by Sri Lanka throughout the period and it has increased its foreign indebtedness beyond its ability to service.

For instance in the next 12-month period, the repayment of debt and payment of interest on such debt will be about $ 6.2 billion; as against these commitments, the free foreign reserves available have been only $ 7.7 billion. If Sri Lanka is to use its foreign reserves to defend the rupee, it has a space of only $ 1.5 billion. This has reduced the Central Bank to making a critical choice: what would happen to the Sri Lanka Rupee after it has spent the freely available reserve of $ 1.5 billion?

Thai fiasco should be a learning point for Sri Lanka

Countries which have gone for this choice have ended up with extremely bitter results. For instance, as I have documented in my book titled ‘Central Banking: Challenges and Prospects’ (p 191) just prior to the Asian financial crisis of 1997, the Bank of Thailand in a vain attempt at defending the Thai Baht at 25 Baht to a dollar had spent about $ 25 billion out its reserves. When the reserves were all exhausted, the Bank had to allow the Baht to go for a free fall causing it to decline to a level of 50 Baht to a dollar.

The Governor of the Bank, Rerngchai Marakanond, was later charged by the Government for losing the nation’s precious foreign exchange balances. On being found guilty, he was imposed the biggest fine in Thai history amounting to Baht 186 billion which was equivalent to $ 4.6 billion. Hence, it is a risk for a central bank to lose the nation’s foreign reserves to vainly defend the currency when the market forces are all exerting pressure for it to depreciate.

When the market pressure is high, no amount of foreign currency sale will help Sri Lanka

This is a choice involving Devil’s Alternative, as described by the British novelist Frederick Forsyth in his novel under the same title. When someone is faced with the Devil’s Alternative, whatever he does leads to enormous costs. This was amply described by Governor Indrajit Coomaraswamy when he addressed a recent summit in Colombo (available at: http://www.ft.lk/top-story/Crux-of-currency-crisis-/26-663273).

Drawing on two failed examples from Sri Lanka’s recent past, he is reported to have revealed that during 2011/12, the then administration of the Central Bank had spent $ 4.2 billion out of its reserves in a desperate bid to defend the rupee. Yet, it could not prevent the depreciation of the rupee by 13.5%. Similarly, in 2015, under the present Government, the Bank had spent $ 1.2 billion to protect the rupee only to experience a depreciation of the rupee by 9%.

Sri Lanka today is in the same critical situation. It could spend a massive amount from its reserves which have been built basically out of borrowed money to protect the rupee. But it would then have to default its foreign loan servicing commitments and still allow a free fall in the value of the rupee when it does not have any more foreign reserves to defend the currency. Either way, Sri Lanka is to suffer for failing to address the critical external sector issues in the past.

This is certainly a devil’s alternative for Sri Lanka.

(W.A. Wijewardena, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)