Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday, 1 October 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A choice involving a Devil’s alternative

In the previous part, we looked at how the Sri Lanka rupee has been continuing its one way journey to depreciation ever since the country gained independence from Britain in 1948  (available at: http://www.ft.lk/columns/The-fate-of-the-rupee--Central-Bank-is-caught-with--Devil-s-Alternative-/4-663352 ). Accordingly, the rupee, which was exchanged for Rs 4.76 per US dollar in 1948, could not be maintained at that level even with the strictest set of import and exchange controls till 1977, and in a partially liberalised regime since then. Before 1977, while changing the value of the rupee through deliberate action from time to time, and relying on import and exchange controls to curtail the outflow of foreign currencies, a massive partial devaluation at 65% over the official rate was put in place, through a system officially called the Foreign Exchange Entitlement Certificate or FEEC system.

(available at: http://www.ft.lk/columns/The-fate-of-the-rupee--Central-Bank-is-caught-with--Devil-s-Alternative-/4-663352 ). Accordingly, the rupee, which was exchanged for Rs 4.76 per US dollar in 1948, could not be maintained at that level even with the strictest set of import and exchange controls till 1977, and in a partially liberalised regime since then. Before 1977, while changing the value of the rupee through deliberate action from time to time, and relying on import and exchange controls to curtail the outflow of foreign currencies, a massive partial devaluation at 65% over the official rate was put in place, through a system officially called the Foreign Exchange Entitlement Certificate or FEEC system.

In a gradual adjustment to the rate, the rupee had been devalued by the Government by about 86% to Rs 8.83 per dollar by end-1976. By enforcing the FEEC requirement at 65%, the effective exchange rate that had been applicable to non-essential imports had been raised from this level to Rs 14.57 per dollar. In 1977, when Sri Lanka moved away from the previous fixed exchange rate system to a more flexible exchange rate system, the rupee value was set at Rs 15.56 per dollar, adding a depreciation of about 7% to the previous effective rate. Since then, year after year, the external value of the rupee fell in the market, since the country could not earn enough foreign exchange to meet the demand for foreign currencies by Sri Lanka’s citizens, businesses and the Government. The gap was filled by borrowing abroad, but it added a greater burden to the country since it had to borrow more to repay foreign loans when they matured and pay interest on such loans annually. Today, it was noted, that Sri Lanka was in a very critical situation, forcing it to make a choice involving high costs whatever the course of action it would take. Such a choice is called a ‘Devil’s Alternative’.

Foreign exchange crises in the past

Of course, this is not the first time Sri Lanka had to face such a critical foreign exchange crisis. There were many in the post-independence period. On all these occasions, Sri Lanka sought to come out of the crisis, mostly temporarily, by getting IMF support.

All events of Foreign Exchange crises have been settled through IMF support

After the JVP insurrection of 1988-9, the country’s official foreign reserves, mainly held by the Central Bank, had fallen from a peak of $ 522 million in 1984 to $ 291 million in 1989. The former was sufficient to finance 3 months of future imports; but in 1989, it could finance only a little more than a month’s imports. On this occasion, Sri Lanka was rescued by an Extended Credit Facility or ECF of SDR 336 million arranged in May 1991. Bur the rupee was allowed to depreciate from Rs 40 per dollar in 1990 to Rs 46 per dollar in 1992, marking a depreciation rate of some 15%. The next crisis came in 2000, when official foreign reserves fell to $ 1049, which was sufficient only for financing 2 months’ imports. A Stand By Arrangement or SBA of SDR 200 million was hastily arranged to overcome the crisis but the rupee had to be allowed to fall to a level of Rs 96.73 per dollar by end-2002.

The next crisis hit the country in 2008 at the tail end of the LTTE war, when the official foreign exchange reserves fell to $ 2560 million, sufficient for financing imports only for 2 months. IMF rescued once again, through a mega SBA of SDR 1654 million in July 2009.

In 2015, again the country went into a foreign exchange crisis, with a fall in foreign reserves and an increase in its foreign loan repayment commitments. Reserves fell to $ 6019 million, which was still sufficient to meet a declined level of 3 months’ imports. But the short-term foreign loan repayment commitments had increased to $ 4300 million, reducing the import capacity of the freely available reserves to slightly more than one month. The Government, sitting on the problem by looking for non-conventional remedies like getting funds from an anonymous Belgian benefactor, delayed any support program from IMF. When the situation became critical and the country could no longer continue with no action program, it went for a mega Extended Fund Facility or EFF of IMF, amounting to SDR 1070 million in June 2016. But by that time, the rupee had depreciated from Rs 131 per dollar at the end of 2014 to Rs 149.80 per dollar by end 2016. Thus, the current crisis has hit the country while it is on an IMF support program.

The present Government’s pledges for reforms

Sri Lanka, in its letter of intent addressed to IMF under the signatures of the country’s then Finance Minister Ravi Karunanayake and Central Bank Governor Arjuna Mahendran, had pledged that the Government would undertake six pillars of economic reforms to support the goals relating to medium to long term economic growth to be facilitated by IMF’s EFF.

The reform program promised by the Government had covered measures to improve the Budget and its revenue mobilisation, enhance the management of public finances, undertake reform of the public sector enterprises, introduce a facilitating trade and investment program, and change the central bank’s monetary policy action from controlling money supply to directly attain a pre-planned inflation level.

But the most important reform the Government had pledged has been, in the words of IMF, the following: ‘A return to fiscal consolidation, targeting a reduction in the overall fiscal deficit to 3.5%of GDP by 2020, is the linchpin of the reform program. Rebuilding tax revenues through a comprehensive reform of both tax policy and administration will be key in this regard, supplemented by steps toward more effective control over expenditures and putting state enterprise operations on a more commercial footing’ (available at: https://www.imf.org/en/news/articles/2015/09/14/01/49/pr16262).

IMF support is a facilitator for the Government to take measures for sustained growth

One might wonder why, with such generous IMF support, Sri Lanka could not resolve its foreign exchange crisis permanently. This is because IMF support is a facility given to the Central Bank to temporarily fill the gap in the balance of payments.

It is expected to give a breathing space for the country to introduce growth-friendly economic reforms, to place the economy in a long-term economic growth trajectory. In fact, when seeking the IMF support, governments on their own pledge to implement a series of economy-wide economic reforms. However, when it came to implementing them, the commitment shown by past governments had mostly been partial.

Consequently, all past IMF support programs were mere financing facilities, with little or no impact on the country’s growth momentum. Hence, it is not the IMF support that should be blamed for the country’s failure. It is half-hearted initiatives of the past governments that should take full responsibility for its failure.

Unproductive deficit financing has been the root cause

In term of the pledge given by the Government when it sought IMF support in mid-2016, it had planned to hit the root cause of the present currency crisis. That is, the profligate Government expenditure programs, which have done little to improve the country’s productivity to sustain economic growth in the past, have been the main perpetrator of the continued currency crisis.

This is intuitively understandable since the new incomes created by the Government, by running budget deficits of significant amounts year after year, have flown out of the country by way of persistently rising imports. In a small open economy, this is the worst option which any government would have gone for. Even John Exter, the architect of Sri Lanka’s Central Bank had warned of this policy option in his report submitted to the Government on the establishment of a Central Bank in Ceylon, known as the Exter Report.

But this warning had fallen on the deaf ears of all the Finance Ministers of post-independence Sri Lanka, except M D H Jayawardena, who held the position during 1954-6. It was only during his time, both in 1954 and 1955, that Sri Lanka had a surplus budget in all its history. In all other years, the Government budgets had been characterised by liberal expenditure programs, financed by a combination of borrowing and money-printing through the central bank. These profligate expenditure programs in turn led to increase the country’s public debt on the one hand and generate inflationary pressures, on the other. The final result has been the generation of balance of payments shortfalls on a continuous basis thereby putting pressure for the exchange rate to depreciate in the market.

No space for import controls

Now that the foreign exchange crisis has become acute and the country has been left with a dangerous ‘Devil’s Alternative’, desperate attempts have been made by the country’s political authorities to reduce the import flow as a matter of priority. However, Sri Lanka’s import structure has been heavily skewed toward the import of intermediate goods and investment goods, and not toward the consumption goods.

Intermediate goods, which account for about 55% of the total imports, are needed to provide inputs to production processes. Investment goods, accounting for about 23%, will supply capital goods to enhance the country’s production boundaries. Hence, attempts at curtailing them drastically will bring in the undesired repercussion of stunting future economic growth.

In such a situation, it is the consumption goods that amount to $ 4.5 billion or 22% have been the target for curtailment. There again, when essential food items and medicines are excluded, the consumer goods base that could be curtailed without immediate disastrous effects is reduced to about $ 1 to 1.5 billion. Since all these goods cannot be curtailed immediately, and it is not desirable to do so either, the Government may seek to brand them as inessential imports and curtail them by about $ 1 billion. But that would be an insignificant amount given the enormity of the problem being faced by the country today.

Attack on vehicle imports after the horse has bolted from the stable

In order to curtail the flow of vehicle imports to the country, the Central Bank earlier imposed a 100% margin requirement on all vehicle imports except those for commercial purposes (available at: https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/en/node/4093).

However, most of the private vehicles that come to Sri Lanka today are supported by duty-free licenses issued by the Ministry of Finance to Parliamentarians or public servants. The permits issued to both categories had a ready underground market price, ranging from Rs 2 million in the case of public servants, to Rs 3 million in the case of others. The Ministry of Finance had promoted the issue of permits by reducing the frequency from 10 years to 5 years in June 2018.

The result was the proliferation of the permits available for sale in the underground market, denying revenue to Government on the one hand, and leaking the benefit from the true public servants to others on the other. Hence, to support the Central Bank’s move to curtail the flow of private vehicle imports, the Ministry of Finance has last week suspended the use of permits, in the case of Parliamentarians for one year and public servants for 6 months.

But almost all Parliamentarians are reported to have availed themselves of this facility already, the suspension made by the Ministry appears to be non-binding on them. In the case of public servants too, the majority of them have already used their vehicles permits. It therefore appears that the door of the stable has been closed by the Ministry after the horse has already bolted.

Address the issue at the source and not at the end

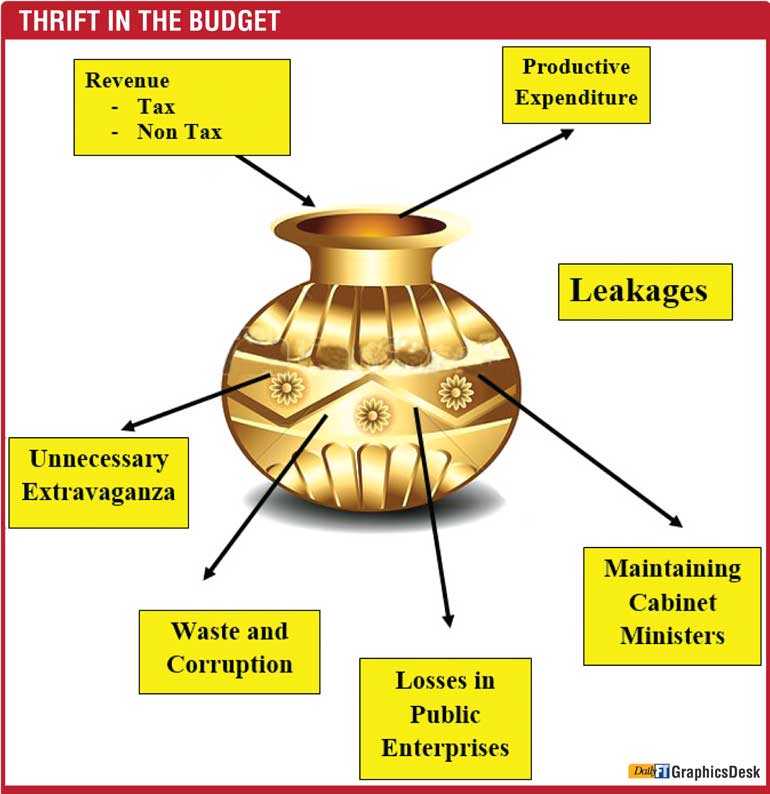

These measures are therefore providing only a signalling effect to the market. They have tried to fix the issue at the end rather than at the beginning. The more appropriate measure would have been for the Government to go for thrift in the budget. Thrift involves a process of cutting wasteful and extravagant expenditure on one side and improving the revenue base on the other. In a previous article in this series, I had drawn the attention of the Minister of Finance in 2016 to the necessity for plugging leaks in the Government budget by presenting it symbolically in the form of ‘Thrift in the Budget Pot’. That symbol is reproduced again for the guidance of the present Minister of Finance.

Government should reinforce the Central Bank’s measures

The Central Bank alone cannot stabilise the external value of the rupee. For that, the Government should extend a helping hand to strengthen the Bank’s initiatives. That can be done by going for thrift at all levels of the Government. It is not too late for the Government to go for it now.

(W A Wijewardena, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected])