Friday Feb 27, 2026

Friday Feb 27, 2026

Tuesday, 12 June 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

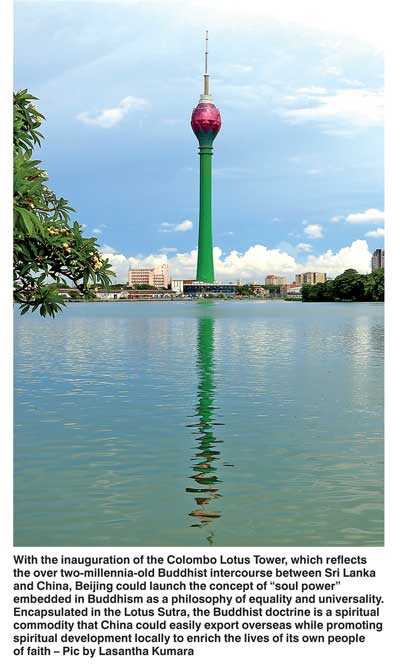

China will soon inaugurate the 350-metre-high Lotus Tower in Sri Lanka, the tallest telecommunication-skyscraper in South Asia. The tower, emanating from the Lotus Sutra in Buddhism, is a narrative for Beijing to formulate a sustainable and peaceful “soft power” strategy that would appeal globally. Because religion has a mutually beneficial “causal impact” on the lives of people and state, especially in civilisational polities like China and Sri Lanka.

For China, will the emerging culture of religiosity be then more successful in governance and diplomacy?

Supporting his “New Era,” the perennial President Xi Jinping has embraced religious faith as part of his “China Dream” and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The nominally atheist Communist Party of China (CPC) has now recognised that religion in Chinese history had served as a powerful tool in domestic governance and international diplomacy. For President Xi’s “rejuvenation” of Chinese nation and national culture after the Century of Humiliation, this mix of faith and politics constitutes a “reimagining of the political-religious state that once ruled China,” according to Ian Johnson, author of The Souls of China.

The freedom of religious pursuits

When the president’s father Xi Zhongxun was the head of the CPC’s religious work in 1980, the famous Document 19 warned the party members from banning religious pursuits because it would isolate the Chinese people. Ever since, China has been restoring the places of religious worship—temples, mosques, and churches—once destroyed by Chairman Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution.

After years of material development through the liberalised trade policies and the opening-up policies of Deng Xiaoping, President Xi said, “if the people have faith, the nation has hope, and the country has strength” to realise a “virtuous and harmonious society” at home and to create a global “community of shared destiny.”

Some Chinese strategists are convinced that the ancient Chinese philosophy rooted in the belief of tianxia (“all under Heaven” as brothers and sisters) had been long-lasting in the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BC). Therefore, it could still be instrumental in governance and diplomacy, where China is the “new” Middle Kingdom with a Mandate of Heaven bestowed upon the emperor, the Son of Heaven.

Referring to the Chinese rejuvenation by highlighting their teachings on obedience and order, President Xi often quotes Confucius, Mencius, and other ancient sages and promotes “the idea that the party is the custodian of a 5,000-year-old civilisation.” For others, China envisions a more harmonious world with Beijing’s definition of a “community of common destiny” through Confucianism.

The hole in the China model

In all this, China has been trying to project its “soft power” through the promotion of Confucius Institutes as a cultural “export.” Beijing has, for example, set up over 500 institutes in more than 140 countries while almost half-million students from over 200 countries are studying in Chinese universities. Although the study of Chinese culture and language has become more popular for financial reasons, the China model is weak. It lacks a universally accepted value system compared to the ideology of freedom and democracy in the West that is widely shared by the world—and even the Chinese people, particularly the 60-million strong Chinese diaspora.

The pervasive efforts to popularise the China model has recently been criticised in the United States. Senator Marco Rubio, chairman of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, accuses Beijing for “exporting authoritarianism with Chinese characteristics”.

The Canadian Security Intelligence Service expressed concerns that “some politicians” are under the influence of China, especially concerning the Canadian policies toward Beijing. The Chinese-Canadians also feel the fear of China’s rising power as they exercise their “Canadian values” of freedom, democracy, and human rights.

In a multi-country report of the US National Endowment for Democracy, the authors contrasted the soft power of China’s charm offensive of “information warfare” with that of “sharp power,” which “pierces, penetrates, or perforates the political and information environments in the targeted countries.”

Speaking before the US Senate Intelligence Committee alongside with the chiefs of other American intelligence agencies, FBI Director Christopher Wray said that “the whole of Chinese society is a threat to the US” and China undermines America’s “military, economic, cultural, and informational power across the globe.” Other democratic countries like Australia and New Zealand have also documented the infiltration of China’s authoritarian influence on their political, economic, and educational systems.

The negative global public opinion has increased as Confucianism and authoritarian governance have reinforced each other beyond the Chinese borders. Beijing needs an alternative soft power of attraction for China’s history and culture. Buddhism would most likely serve as a “soul power” of China as Beijing has tried to expand it through China’s BRI and its new globalised Buddhist network. This is because that Buddhism has had a historical appeal as a spiritual “import” to China and then successfully “export” to East Asia and the world.

The spiritual footprints of soul power

As a re-emerging global power after the Century of Humiliation, China has indeed recognised that the civilisational-state evolved with the influence of Confucian ethics and its hierarchical philosophy—and the integrated Marxist ideas—needs to be recalibrated. Essentially, China needs a new brand of universal appeal to win over the hearts and minds of global citizenry.

With the inauguration of the Colombo Lotus Tower, which reflects the over two-millennia-old Buddhist intercourse between Sri Lanka and China, Beijing could launch the concept of “soul power” embedded in Buddhism as a philosophy of equality and universality. Encapsulated in the Lotus Sutra, the Buddhist doctrine is a spiritual commodity that China could easily export overseas while promoting spiritual development locally to enrich the lives of its own people of faith.

After all, Buddhism had always been an invisible attraction as Imperial China effectively integrated the Buddha’s Dharmic teachings as its own with those of indigenous Daoist traditions and Confucian ethics. The universal teachings and ideas of equality (especially among men and women) rooted in the Lotus Sutra must continue to serve as the forerunner of China’s peaceful identity and national unity that exemplifies a better world order.

Harvard Sinologist John Fairbank writes that “Confucianism was largely left in eclipse and the Buddhist teachings as well as Buddhist art had a profound effect upon Chinese culture, both north and south,” despite the dominant societal values of Confucian hierarchy of Imperial China. Professor Fairbank further states that the teachings of Buddhist Dharma “offered an explanation and solace, intellectually sophisticated and aesthetically satisfying, for the collapse of their old society. Emperors and commoners alike sought religious salvation in an age of social disruption.”

During the Sui (581–618) and Tang (618–907) Dynasties, for example, Buddhism served as a potent force for unifying the Middle Kingdom and expanded diplomatic and trade relations with foreign nations on the ancient Silk Road networks. Even foreign invaders—like the Mongol and the Manchu—used Buddhism to earn respect from the Chinese people as well as to solidify their state-power during the Yuan (1279-1368) and Qing (1644-1912) Dynasties.

Under President Xi, China has once again returned to a somewhat familiar pattern of social and political upheaval. The president, who replaced Deng Xiaoping’s earlier motto of China’s “Peaceful Rise,” must resort to China’s invocation of its “peaceful identity” in the midst of intensified regional tensions in the South and East China Seas, the Korean peninsula’s denuclearisation efforts, the controversial opening of China’s first military base in Djibouti in Africa, the boiling Indian-China border issue with Bhutan, and elsewhere.

The answer from the Lotus Sutra?

The forces of opposition are also appearing from every other corner of the world. The foremost is the new National Security Strategy, in which the Trump White House identified China as a “revisionist” power and a “strategic competitor.” Furthermore, Washington has now taken the lead in the new “Quad” coalition of Australia, Japan, and India against Beijing’s imperial overreach. Even the democratic Sri Lanka has raised the question of China’s intentions as if the Lotus Tower were a new form of Trojan Horse.

Yet China moves ahead with its BRI plan as the Colombo Lotus Tower was originally designed to signify the symbol of Buddhist peace. Thus, Beijing needs to promote its “soul power” deep-rooted in Chinese Buddhism and culture where the notion of their Buddhist “pure land” is a sacred nation of religiosity with a blend of Confucian and Daoist origins. Such an integrated narrative that equates the government with Chinese national heritage would serve Beijing better and in more sustainable ways to transform the BRI and the worldview that goes with it.

In fact, President Xi described the island—the Buddhist “Kingdom of the Lion” as the visiting Chinese scholar-monk Faxian (337-422) called Sri Lanka—as a “splendid pearl” during his historic visit to Sri Lanka in 2014. While signing over 20 cooperative agreements, the two countries further recognised the importance of significant Buddhist affinity over the two millennia. The Lotus Tower, which invokes the “universal virtues” of harmony, may revive the coveted noble concepts of equality and freedom inherent in the sutras of China’s Mahayana Buddhism if Beijing truly wants to pursuit a new model of peaceful identity for a pacific new world order.

(Professor Patrick Mendis, a former Rajawali senior fellow of the Harvard Kennedy School of Government’s Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, is an associate-in-research of the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University and a commissioner of the US National Commission for UNESCO at the State Department in Washington, D.C. He is the author of, most recently, ‘Peaceful War: How the Chinese Dream and American Destiny Create a Pacific New World Order’. The views expressed are his own.)