Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday, 24 September 2020 00:28 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

|

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg

|

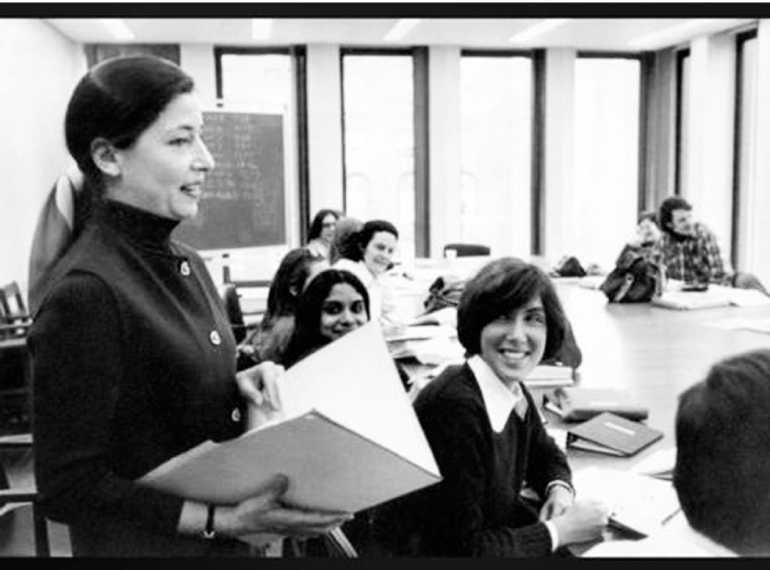

A diminutive, shy person with head bowed down walked into the room. She walked slowly but with a purposive step. When she began the class her voice was just above a whisper and her words were accompanied by long pauses as we strained to listen. This was 1976 and I was enrolled in the class of Professor Ruth Bader Ginsburg as she began her pioneering course on sex-based discrimination and the law.

As a South Asian I was used to vibrant and colourful women leaders. Ginsburg was anything but. With a cold, piercing, powerful, intellect, she showed us how to dissect arguments, plan a cohesive strategy and win the battle. She was all about the analysis, the details and the hard work. Her main area of interest in the law was Civil Procedure, the rules and processes of the legal system. I usually fell asleep during those classes but it was Ginsburg who convinced me that if you are going to be a human rights lawyer, first master the procedure. Your passion will guide the substance.

There are three main eras to Ginsburg’s legal career. The first that began in the sixties and went through the 1970s was to try and radically transform the law through persuasion, especially persuasion of the US Supreme Court. The second phase involved her engaging in the “art of the possible,” working with judges across the spectrum to get moderate, consensual judgments. Her last and most iconic era was the “I dissent” phase where Republican appointments to the Supreme Court threatened her values and all that she stood for.

Writing strong, fiery dissents, she inspired young students who began to call her the notorious RBG after the rapper who recently died. She became a pop icon; there were tee shirts, people tattooed her face on their bodies, posters with her quotes were put up all over and all kinds of paraphernalia were created. In her raspy voice, born of years of experience, she insisted on reading these dissents from the bench in her slow steady pace, painfully reminding people of the values the country was losing.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg was a member of that generation of women who went into the professions in the 1960s. She was pioneering but was also directly discriminated against and knew what it was like to be on the other side of privilege. When her husband was drafted into the army and she tried to find work as a pregnant wife, she was given lower pay and was told that she would have to leave once the baby was born. She was one of nine women students in a class of 500 at the Harvard Law School. The Dean asked her how she felt about taking a man’s place. She was so flabbergasted that she said she did it to understand her husband who was also a law student.

She was tied for first place in her class on her graduation from Columbia Law School where she had moved because of her husband’s employment. If she were a man she would have had a pick of the Supreme Court Justices she could clerk for in the US tradition but even the revered liberal judge Felix Frankfurter said no that he would prefer a man. Denied all opportunity befitting her degree in public or private employment she took to academia becoming one of the first female professors of law at Rutgers and Columbia.

When I was at Columbia Law School she was the main female professor who taught civil procedure and sex-based discrimination. The few other women lecturers taught ancillary subjects. Testosterone ruled the halls of these law schools and we knew we were accommodated as a few add-ons. From those interactions many feminist crusaders were born.

In the early 70s, Ginsburg was asked to head the Women’s project of the American Civil Liberties Union, the premier human rights organisation in the country. She attached it to a student “clinical” at Columbia Law School so students could be part of the litigation. At that time a major controversy was gripping the United States. Conservatives argued that if women want equal rights they should get the US Congress and the States to pass an amendment to the Constitution – an Equal Rights Amendment – as the African Americans had done after the civil war. An attempt to pass this amendment was made but as is always the case in the US, the few red states stopped its progress. The conservative heartland raised all sorts of Trumpian fears of men having to share bathrooms with women and posed the effort as a threat to married women.

The failure of the attempts to pass the Equal Rights Amendment did not dishearten Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Her strategy was less political and more legal. She wanted to move the issue of sex-based discrimination before the US Supreme Court as part of the Bill of Rights and not in the legislature, which is often the site of unwieldy prejudices. Sex discrimination would be framed as a protection of a basic fundamental right contained in the Bill of Rights.

The ‘separate sphere’

At the time she argued her cases, the doctrines in the Courts with regard to women were quite shocking. The controlling doctrine was one that was called the ‘separate sphere’. Women occupied a separate sphere than men so equality was not a concern or an issue. The famous words were from the concurring judgment of Justice Bradley in Bradwell vs. Illinois. “The natural and proper timidity and delicacy which belongs to the female sex evidently unfits it for many occupations of civil life… The paramount destiny and mission of women are to fulfil the noble and benign offices of wife and mother”.

Ginsburg was determined to overturn this century-old judgment. Along with other ACLU women lawyers she pegged her argument to the 14th amendment of the US Constitution. This equal protection amendment was adopted at the end of the civil war to eradicate slavery and give Black Americans equal rights. Though its specific history was for Black people in America the wording spoke about “persons” who were entitled to these rights. Ginsburg wanted the court to go beyond legislative intent and hold that equal protection extends to women. What appears to be self-evident now was not the case 50 years ago and one had to argue every step of the way.

With a masterful strategy, winning five cases out of six in the early 1970s, she got the US Supreme Court to extend equal protection to women and to create a framework to prevent discrimination based on sex. Gender as a concept had not emerged. Ginsburg was not able to get “strict scrutiny” of any legislation that mentions sex but she managed to get them to agree to an “intermediate” scrutiny. “Strict scrutiny” on behalf of women would only come one gathers with an Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution that was being resisted by the conservative states of the mid-west.

All the equal rights that women in the US enjoy today are due to Ginsburg’s litigation and the decisions of those judges. This constitutional regime then gave coherence and a framework to the many laws passed by Congress for women’s education, employment and violence against women. By being interpreted as part of the Bill of Rights, individual states are also held accountable, ‘red neck’ or otherwise.

Framing sex discrimination in a way that would make men understand

Ginsburg’s strength that made all this possible was careful planning. Today when we do women’s rights work, a great deal of emphasis is placed on advocacy and communications. Ginsburg’s strongpoint was strategic detail. One case she brought before the Court involved a male petitioner. His wife had worked all her life but there were no benefits for him when she died though her co-workers who were male left benefits for their wives. Ginsburg argued this type of practice not only devalued women’s work but also discriminated against men. She took these cases to show that discrimination on any grounds was not permissible. The male justices could feel empathy and better understand discrimination.

Many radical feminists may feel this is not a correct strategy and too self-effacing. But it was 50 years ago, a very different time and nothing seemed possible. Ginsburg framed sex discrimination in a way that would make men understand. In this way she swayed and persuaded the male justices of the US Supreme Court and created the precedents that exist today. Without her creative and thoughtful strategies women would not have attained equal status before the law even in the 1970s.

In many ways, our priorities have changed. Today a great deal of women’s rights advocacy women involves activism around violence against women. The private violent male abuser that haunts our literature today was not a preoccupation of the early Ginsburg, though in her later years she would endorse the Me Too movement. The issue of violence against women only became a global movement in the 1990s.

Ginsburg always saw men as allies. This may also be in part because of her extraordinary marriage. She met her husband at Cornell University and they were together till he died a few years ago. She would invite students home and he would cook for them. He took care of the children when she did her frequent all-nighters. He was fully supportive of her career and work. She never fails to thank him and despite her many health problems she always gave the air of being secure and happy.

In 1980 Ginsburg gave up this life as a ‘flaming feminist litigator’ and was appointed to the Court of Appeal by President Jimmy Carter. She stayed there till the 1990s when President Clinton appointed her to the US Supreme Court. She settled into the role of a ‘moderate’ judge, a ‘consensus builder’, working as a team with her colleagues. She was known as a cool headed and fair judge. This is a quiet era in her biography and there were few landmark cases or decisions that she authors. She defers to the other great liberal judges on the Court.

‘I dissent’ era

Ginsburg only came into her own during the latter part of her tenure, when the Supreme Court had lost its liberal majority and hard right wing opinion began to make its mark reversing years of progress. She moved into her ‘I dissent’ era. Her ‘I dissent’ became legendary as she spoke her words from the bench and as her language became more fiery and on edge. This is the era that would earn her the reputation of being notorious.

She began as usual with women’s issues. She wrote for the majority when she argued that women should be allowed entry into the Virginia Military Academy using the equal protection argument that she had weaved in the 1970s. Interestingly, many women from peace groups felt women entering the military should not be a priority of the women’s movement. Ginsburg was not one of them; she wanted all doors open. The military wielded enormous power and influence. She believed that women should be part of the decision-making.

Abortion was the other women’s issue that made her bold during her ‘I dissent’ phase. For a long time the US Supreme Court had accepted abortion as part of the right to privacy, a penumbra of the first amendment of free speech and expression. Ginsburg in one of her ‘I dissent’ judgments, beleaguered by violent, anti-abortionist activists, argued in her dissent that the right to abortion rested with the notion of women’s autonomy and her right to determine what happens to her body. This was the feminist position and not the historical position of the Supreme Court. She felt the doctrine should shift from privacy to autonomy and that the Court should move more boldly in the protection of women’s rights.

Ginsburg also began to publicly stand for her beliefs in a country that had grown conservative as well as apathetic. After the Supreme Court decision validating same sex marriages a few years ago, Ginsburg made it a point to officiate at one such ceremony. This surprised many people. At the end of her life she had come out of her shell. She became the flamboyant advocate she often warned us not to be. The situation was so horrendous in her eyes that it called for public displays of bonding and caring. She is not at ease in such situations and her awkwardness is palpable. Yet she decided to go ahead, face the publicity head on and stand up for the values she held dear.

Ginsburg is known for her work on women’s rights issues but she became a public icon when she fiercely dissented in the Voting Rights case of 2013. The Voting Rights Act was brought by Congress to remedy the unequal practices at the state level that prevented black people from exercising their right to vote. Suppressing black American votes and gerrymandering was frequent in many US states and still go on even today. In 2013, a Republican Congress passed a law limiting the Voting Rights Act assuming that the goals had been reached. It was a terrible act of partisanship. Ginsburg was furious. Quoting Martin Luther King and his I have a dream speech she was scathing about the content of the law and the intent of the legislature. Quoting King again she said, “The arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice”, but with a steely dissent she added, “if there is steadfast commitment to see the task through to completion”. People were amazed to see such strong language from her and thankful that it came from a Supreme Court justice. She became a star.

All icons have their flaws and Ginsburg is no exception. She was not really strong on migrants’ rights, she did not side with indigenous people in an important case in 2005, and throughout the war on terror her voice has been relatively muted. Criminal justice issues were not her strong point even when the country was being ravaged by draconian actions by state security agencies. The war on terror initially left her cold. She just would not go there. She let other liberals write the judgments or dissents and she would agree or concur. She always felt that she lacked the expertise.

Inter-generational success

The Ginsburg story is also about the possibility of inter-generational success. Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s mother was a factory worker who sacrificed everything for her daughter to get an education and do well in life. She told her daughter some home truths that Ginsburg often repeats in interviews. Like Barack Obama who also dwells on this topic in his autobiography, she makes clear that her mother told her to always control her anger. For most of her life she lived according to that rule and was inspired by a spirit of cautious radicalism. In the early stages she never showed her anger.

Ginsburg was also incapable of hate. She always kept the door open. In her late years her best friend was Justice Scalia her absolute opposite when it came to judicial opinions. They often went to the opera together and Ginsburg actually performed in one Opera as she was an extraordinary woman of talent. Ginsburg had no harsh words for those who intellectually opposed her. In that sense she was a classical liberal.

Though she never hated, though she treated her rivals with respect, her last years challenged her mother’s words on anger. For all those who were her students, for all that training we also got on controlling our anger and focusing on the law, we watched with amazement as her rage began to unravel. From 2009 she began to come into her own. She began to take control of the liberal court, especially after the resignation of the other female judge Sandra Day O’Connor.

When there was no one else on the bench to stand for what she felt were eternal values she spoke out with words and language that were so strong that they were in fact vulnerable. As a result her genuineness reached common people, especially young people. As time raced against her and as she raged against the fading of the light, she gasped even with her last breath for justice to be done.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg as Professor of law at Columbia University in 1976 with the writer Radhika Coomaraswamy as one of her students