Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Monday, 8 January 2018 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

President Maithripala Sirisena and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe

On 8 January 2015, the Sri Lankan polity experienced an unexpected change. A President who planned to rule until he could hand over power to his son lost by half a million votes to a defector from his own party. President Sirisena won with the support of a motley mix of political parties and groups with the United National Party at the helm.

Now beyond the halfway point of the Presidential term, it is opportune to assess the achievements and failures of the Government.

Reversing State capture

South African President Zuma’s behaviour has popularised the term “state capture,” even leading to its use in judicial decisions. But Sri Lankan politicians mastered the art of state capture well before Zuma, as exemplified by the operations of the CSN broadcasting company with privileged and possibly under-priced access to real estate, spectrum and cricket broadcasting rights; and by the criminal misappropriation verdict against the then Secretary to the President and the then Director General of Telecommunications.

The approval of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution limited the President to two terms while considerably reducing the powers of the office and created independent commissions. That and the coming into force of a strong Right to Information Act make State capture more difficult. But laws alone are not enough. The existence of different power centres within Government made possible the replacement of a questionable Governor of the Central Bank and the appointment of a Commission to investigate malpractices associated with bond transactions during his term.

State resources are still being used for private gain, but it is harder now. A Minister was removed when evidence of State capture was revealed, unheard of before 2015. While the whole country is aware of his malfeasance, the criminal indictments are yet to be filed. The verdict on the criminal misappropriation of Rs. 600 million from the Fund of the Telecom Regulatory Commission has been appealed. This is how reform works, not like turning on an electrical switch, but gradually and incompletely.

The existence of different power centres within the State (the Constitutional Council, the Elections Commission, a less-powerful Presidency balancing against a more-powerful Prime Minister and Cabinet, etc.) is a necessary condition. But the sufficient condition for reversing State capture is an active citizenry able to voice their concerns through the media. The glass is half full, though we could wish it was fuller.

Reducing incoherence of economic policy

The Government’s economic policy was adrift in the first two years, but a course correction has been made. In the words of an insider, a Senior Advisor to the Government Razeen Sally: “What has clearly made a critical difference is the mid-year cabinet mini-reshuffle, when Samaraweera replaced a Finance Minister who delivered disastrous budgets, held up market reforms for two-and-a-half years, and was a national and international embarrassment.”

In a modern, complex economy the Government must maintain policy consistency and communicate its policy positions clearly. This allows other economic actors to go about their business, confident that assumptions in their business plans will not be nullified and their capital will not be administratively expropriated (or nibbled away by capricious taxes and demands for donations and so on). This, sadly, was not what happened in the first two years.

National policy formulation is no longer under the Minister of Finance. The subject has been under the Prime Minister since 2015. This requires all Ministers, especially the Minister of Finance, to act in a manner consistent with the policy directions of the Prime Minister. This was not the case in the 2016 and 2017 Budget speeches which were not only incoherent but were also unimplemented for the most part as shown by Verite Research.

The 2018 Budget was a lean document consistent with the previously presented Prime Minister’s Economic Policy Statement and Vision 2025. It shared some of the weaknesses of previous budgets, in presenting budgetary measures intended to promote behavioural change in economic actors without adequate research and preparation. However, these shortcomings are part of the pervasive pattern of under-researched, half-baked policy proposals that keep being produced by the Sri Lankan state machinery.

Many important initiatives exist outside the Budget, as should be the case in a modern, complex economy. In some cases, the ideas are good but execution doubtful.

An example is the $ 169 million agricultural sector modernisation project, a well-thought-out project intended to connect smallholder farmers to global supply chains using the instruments of matching funds and bank guarantees. It is managed by the Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Primary Industries with a State Minister also added to the mix. More than a year into a five-year project, only 2% of the funds has been disbursed and no progress has been recorded under any of the project performance indicators stipulated in the project documents.

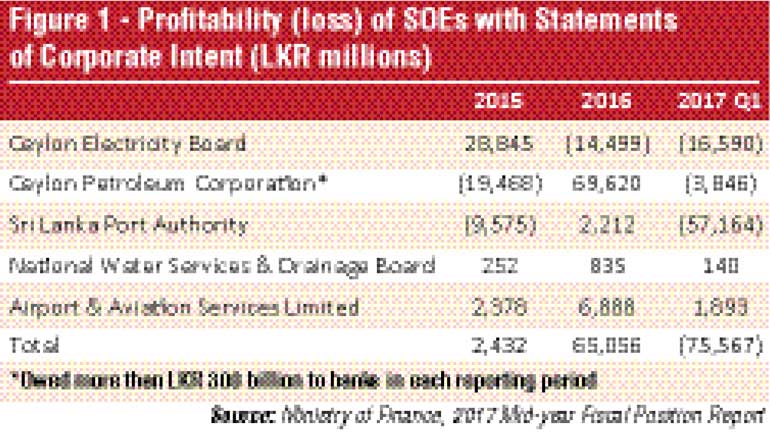

Given the proliferation of dysfunctional State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) and re-nationalisations in 2004-15, the establishment of a Ministry of Public Enterprise Development helmed by a powerful Minister was welcomed. Its principal output appears to be ‘Statements of Corporate Intent’ (SCI) signed with five big SOEs (surprisingly excluding SriLankan Airlines and Sri Lanka Telecom).

The performance of the SOEs has declined after the SCIs were signed. The losses in the First Quarter of 2017 alone were larger than the net profits of 2015 and 2016 combined.

The disastrous situation of SriLankan Airlines, another of the Ministry’s wards, is well known and need not be described here. Despite clear evidence from an unsuccessful effort at partial divestment, the government has not accepted the need to stop the haemorrhage of taxpayer money by selling the airline outright, even if for the value of terminal rights at Heathrow. The glass is more than half empty as far as fixing public enterprises are concerned.

Execution

The ultimate test, of course, is execution. Many of the Government’s proposals are overly complicated and difficult to implement within the political cycle, let alone the even shorter budgetary cycle.

The solutions for other problems such as stanching the destruction of taxpayer equity by mismanaged SOEs, are known, but modus vivendi between parties which constitute the national government appear to preclude implementation.

The tragedy is that even pragmatic, second-best solutions such as the entering into individual performance contracts with members of SOE boards and making such appointments performance- not patronage-based, are not being implemented.

Signing performance contracts with each and every Minister and making their reappointment conditional on performance is a broader solution that has been proposed but ignored. If this is done (and Ministers who fail to meet performance criteria sent to the back benches), overall performance of government would increase; state capture would decrease. The demand for Ministerial positions may even decrease.

The efficacy of any of these measures requires citizen engagement. The failure of the fiscal responsibility legislation enacted in 2003 illustrates that law by itself is no barrier to politicians and officials colluding in state capture. In economic matters too, it is praiseworthy that the necessary conditions for good governance have been put in place. Citizens making effective use of them is the sufficient condition.

It is only then that we will be able to confidently affirm that the glass is half full.