Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Tuesday, 23 October 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

As the Ministry of Megapolis correctly points out, the landfill is sanitary, is located in a sparsely populated area, and Colombo’s waste is everybody’s waste, but protesters are not swayed by such logic. With the memory of the negligence and/or the misdemeanours of the Colombo Municipal Council (CMC), as noted in the Report of the Presidential Commission on the Meethotamulla Garbage Disaster still fresh in people’s minds, the protestors have a point – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

Our policymakers may do the right thing but not do it too well by not communicating the larger purpose of their actions. The current fuss about the proposed Aruwakkalu landfill is one such example.

As the Ministry of Megapolis correctly points out, the landfill is sanitary, is located in a sparsely populated area, and Colombo’s waste is everybody’s waste, but protesters are not swayed by such logic. With the memory of the negligence and/or the misdemeanours of the Colombo Municipal Council (CMC), as noted in the Report of the Presidential Commission on the Meethotamulla Garbage Disaster still fresh in people’s minds, the protestors have a point. Will Aruwakkalu be another dumping place for incompetent local authorities?

In response, the Ministry needs to communicate two important facts to general public – i.e. 1. Almost all of the stinky and ground water polluting food waste and other biodegradable is already removed from the waste before they go the landfill and 2. It is going to be a regulated landfill with carrots and sticks in place for reducing the waste to be dumped.

If the protestors and those who ready to sympathise with any protest are not informed properly in this manner, this country will once again miss an opportunity to address our waste problem.

Protesters should not be allowed to repeat ’80s mistakes

As the Auditor General noted in his 2003 audit report in regard to solid waste management at the CMC: “An agreement had been signed in 1992 between the CMC and the World Bank for an environmental land filling project at the Alupota Estate, Meepe. The project had been abandoned due to opposition from the public. The total expenditure incurred on the project is not available for audit. Alternative sites had not been considered for the continuation of the project and the funds received had been returned.”

One of the actors of the drama, in an article published on the website of the Center for Environmental Justice on 14 January 2009, confesses to being part of a political game: “The sanitary fill proposed at the peak of the debate on garbage had to be abandoned due to public protest. The site moved from Ragama to Alupotha in Meepe. It was proposed to have few central collection stations and bring to the sanitary fill. The scientific and environmental debate on the issues such as best site and best waste management mechanism was transformed to a political game of certain politicians in the area. The slogan ‘No to Colombo garbage’ was a creation of this political game. Although it was not the best solution, abandoning of this sanitary landfill was the biggest mistake. I feel ashamed because I was also part of this debate.”

Eventually, a sanitary landfill at Dompe was constructed, but it is under-utilised because it is in a relatively populated area and the people in the area are not allowing waste from outside of the area. Until 2015, citing unavailability of disposal sites, CMC and others indiscriminately dumped their garbage in Meethotamulla, leading to the disaster of April 2016 with the loss of 31 lives.

60% of waste saved from dumping through differential fees now

A week ago I had the opportunity to visit the Kerawalapitiya Waste Park managed by the Sri Lanka Land Reclamation and Development Corporation (SLLRDC). I was happy to see garbage trucks coming in an orderly fashion, getting their identities checked and tonnage recorded.

Trucks with food waste and other biodegradables went in one direction to be composted and the trucks with comingled waste dumped those into a pile awaiting transfer to a proper landfilling site. Having observed the Meethotamulla site sometime back, the contrast was a painful reminder of what could have been.

After a difficult start soon after the emergency of the disaster, today the park is functioning smoothly. The Ministry of Megapolis was smart in overlooking engineers with paper qualifications to recruit tried and tested expertise to support the SLLRDC.

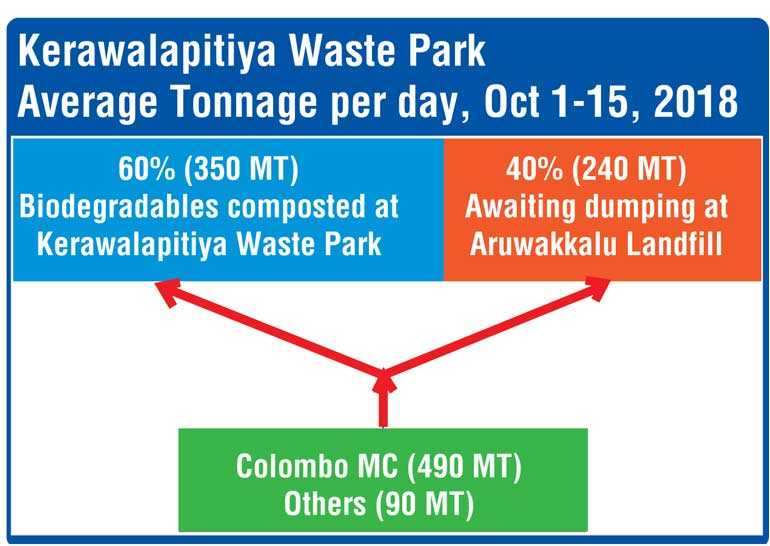

Nimal Prematilake, a public health inspector with an exemplary track record in waste management locally and internationally, is assisting the SLLRDC to manage the operations at the Kerawalapitiya Waste Park. The Waste Park received around 590 metric tons (MT) of waste per day on average during the 1-15 October 2018 period. If food waste and other biodegradables are brought separately, a user is charged only Rs. 3,000 per metric ton. If the waste is mixed or co-mingled, the charge is Rs. 5,000 per metric ton.

From March 2009 until the disaster of April 2016, CMC was sending unsorted waste to Meethotamulla with CMC incurring only the maintenance cost for the site. The estimates of CMC’s daily tonnage vary from 800-900 MT. The wonder of economic incentives is such that, after waste disposal was taken over by the ministry of Megapolis imposing differential fees, CMC found the motivation to reduce the waste to 490 MT per day on average plus separate 60% of waste as compostable food waste and other biodegradable to claim the lower dumping fee. Latest statistics from 1-15 October are given in the graphic.

A simple economic incentive administered and enforced by a central body was all that was needed. It is too late for victims of Meethotamulla, but not too late for bystanders to wake up and defend regulated landfills.

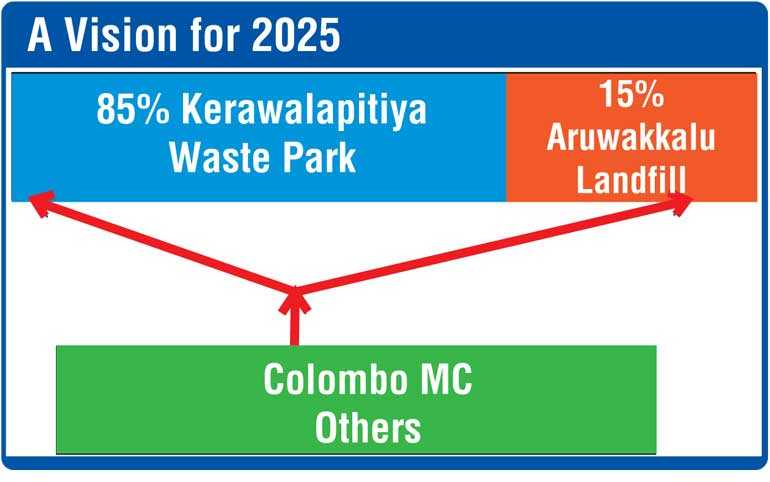

A vision 2028 to reduce landfilling further to 15% or less

If civil society and media is to defend the Aruwakkalu landfill, the Ministry needs to be proactive in not only publicising its success in Kerawalapitiya, but project a vision 2028 where the 40% of mixed waste currently to be sent to Aruwakkalu will be reduced further. In particular it should be communicated to the public that the food waste and other perishables that can cause a stink during transportation and problems in the landfill are mostly removed, and the Ministry will make a commitment to remove those to near 0% in the future.

Sweden, a country which is held up as the epitome of solid waste management, currently recycles 99% of its household waste. Sweden did not achieve this overnight. In 2000, the Swedes were landfilling about 30% of their waste. We don’t have data on previous years when they landfilled more, but current recycling rates of USA and UK are indicative. According to the Environmental Protection Agency of USA, in 2014, the recycling rate of municipal waste in the USA was 35% and the rate in In UK in 2015 was 44%.

In comparison, Kerawalapitiya Waste Park has achieved much since April 2016 to rescue 60% from the waste and leave only 40% for landfilling. With its demonstrated capabilities, it is now possible to envision a future, say, into 2018, when we can have a target of reducing the percent of waste sent to Aruwakkalu to 15% or lower.

This vision can be achieved through further refinement of economic incentives and upgrading of facilities provided through the waste park. The economic incentives have to be refined from the simple formula of two types of waste to a further differentiated formula with a time component added to that. For example, each local authority would have to agree to reduce the percent of waste sent to landfills according to a pre-agreed time table or face hefty surcharges if they don’t.

A Pricing Formula for waste disposal

For example, if CMC is required to reduce the amount they sent to the landfill to 34%, say, from the present 40% by 2020, anything over and above that limit will be charged at almost double the regular rate. Given our experience of local authorities acting without accountability, the best solution is to impose controls such as these at the disposal site. The Waste Park can provide technical assistance but it is up to each local authority to decide what method they would use to reduce the amounts they send for dumping.