Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday, 4 April 2019 00:41 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

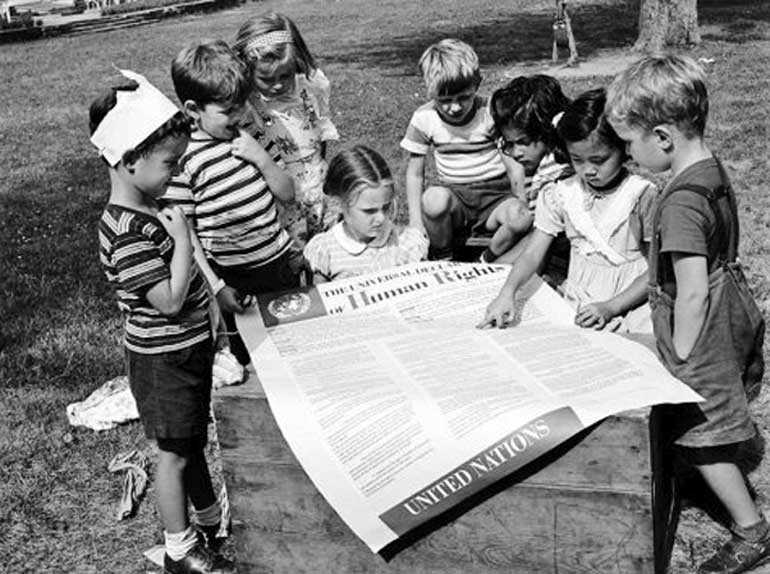

70 years is a long time since the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) by the UN in December 1948. Whatever the marginal biases or weaknesses that it entails, it is a fair statement on human rights that all human beings should have, irrespective of the country, culture, religion, ethnicity, class, social status, ability/disability, gender or any other distinction. Its rationality and validity are based on the human rights commitments outlined in the UN Charter (1945).

The important premise that the human rights promoters and also the UN have to understand however is the fact that the world is so diverse, social, political, economic and cultural conditions are different, so the development of human rights would be a difficult task that requires objectivity, patience, dialogue and multiple approaches. It is not clear whether this is understood properly then or today.

After the Universal Declaration in 1948, the UN adopted more binding two International Covenants in 1966 that became operational for those countries who ratified them since 1976. Those are the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).

With the adoption of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW, 1979) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC, 1989), the international framework for human rights promotion appeared complete with other declarations and conventions.

Need for social approaches

Among all the conventions, the Rights of the Child could be considered most futuristic. If implemented properly, with necessary skills and values in education for children (i.e. social rights), and with gainful employment when they grow up (i.e. economic rights), within few decades human rights situation could be dramatically changed or improved. What is primarily required for such a change and improvement is socio-economic reforms, apart from legal enactments.

It is believed that those children who are abused or deprived of rights are most prone to violate the other people’s rights when they grow up. This is apart from legal, institutional and political conditions that propel or perpetuate human rights violations. A major predicament, however, in this respect is that those who are supposed to implement Child Rights are the old and abusive generations. Apart from the responsible officials, they are partly the fathers, mothers, teachers, religious preachers, and the neighbours. Therefore, the approaches have to be more nuanced and socially oriented.

Women, without sparing men of the responsibility, undoubtedly can be mobilised in this venture. The Rights of Women and the protection of them could play a crucial role in this respect. Women and mothers can be the champions of the futuristic Child Rights. Women rights should not be limited to employment, equal wages, individual freedoms, freedom from abuse and political equality, they should be enhanced to the protection of children. This is a leadership role than a responsibility. This is one reason why women should be brought into politics (not dirty politics) and public life.

Mere ratification?

By the end of 2018, all UN member countries (193) except the US had ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Rights of Women were ratified by 189 countries, but 50 of them with reservations on certain and some important provisions. These were due to certain religious and cultural beliefs.

In the overall context of human rights implementation, the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights can be considered crucially important. The first is important for democracy; and the second for social justice, equality and elimination of poverty. Both are interdependent, but without proper economic and social rights, no one can exercise civil, political or cultural rights properly.

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights is ratified by 172 countries, with 6 other countries including China only signing it, hopefully with the intention of ratifying it in the future. This is fairly a good indication for future of democracy in the world. The Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights is ratified by 169 countries, with four others including the US only signing it.

Ratification of human rights conventions can be considered satisfactory, whatever the reservations placed on some provisions and by some countries. However the ratification is not a guarantee of implementation or adherence to human rights. This is like the proverbial difference or the gap between ‘theory and practice’ or the ‘law and reality.’ Otherwise, the situation in the world today would have been wonderful.

Gaping holes

No one expects any country to be perfect in practicing or implementing human rights i.e. civil rights, political rights, economic rights, social rights, cultural rights, women’s rights and child rights that we have been discussing. However, the gaps are enormous in most countries. For convenience, let us limit this discussion to five main types of overall rights – civil, political, economic, social and cultural.

In liberal democratic countries where civil, political and social rights are fairly established, the economic rights are pathetically lagging behind, and in some countries major aspects of cultural and indigenous rights are also neglected. There are authoritarian countries where almost all rights are neglected or often suppressed although they have ratified most international conventions. Then there are socialist countries, China being primary, where economic and social rights are promoted or fairly established, but civil, political and cultural rights are lagging behind or still neglected.

In the case of China, the size of the country, mammoth population and past history are some inhibiting factors. Social democratic countries in Northern Europe and partly Australasia appear to be the best where two sets of rights are balanced fairly well. They are rated high in the happiness index as well. However, their social democracy moves back and forth with neo-liberalism creating considerable holes.

Most alarming is the gross violations or neglect of basic human rights in so many countries around the world; many countries unfortunately being in the African continent. News and images of extreme poverty, hunger, malnutrition, armed conflicts, wars, gang violence, killings, terrorism, election violations, authoritarian or dictatorial political leaders are prominent in the media. Some may not understand these situations as related to human rights. But underlying causes are related, while obviously there are other factors involved.

Rigid legal approaches

All the above point to some terrible defects in human rights approaches at international as well as national levels. Simply said, the approaches are predominantly too legalistic with colossal neglect of economic and social rights.

There are so many legal experts who draft, draft and draft so many international declarations and conventions on human rights. Altogether there are over 200 international instruments (declarations, covenants, conventions, resolutions, statements etc.) today. They like to call them ‘instruments’! These are mostly in the areas of civil and political rights. After the ICESCR in 1966, there is no significant international ‘instrument’ drafted in promoting economic and social rights particularly affecting the poor and the needy.

Then there have been efforts to persuade or force particularly underdeveloped, poor and former colonial countries to ratify them without assessing their capacities to implement them. There are no proper dialogues involved. It is questionable whether these (or some of these) efforts are genuinely human rights or intentionally political (with economic interests behind). I was partly witness to what went on in Cambodia during the UN intervention (1992-93), where nearly a dozen of ‘instruments’ were forced on the country. By that time there were no more than 10 qualified lawyers in the country even to understand these ‘instruments’ properly. The compulsion to ratify ‘instruments’ has been the case in many other countries, before and after.

There has been a parallel pattern emerged where many developing countries just superficially ratified human rights ‘instruments’ to seek favours from the UN and/or Western countries. As an inducement, there were human rights conditions attached to foreign aid (and trade). Sri Lanka came under this category during J.R. Jayewardene’s time and thereafter.

Sri Lanka’s recent sponsorship of the UNHRC Resolution 30/1 (2015) also has evolved on those lines, going into an absurd extreme. There was a time when the country even was not sure whether it has ratified the First Optional Protocol to the ICCPR or not! If we take all the human rights conventions that Sri Lanka has ratified seriously, the country should in fact be a human rights paradise!

This does not mean that the ratifications of human rights conventions were wrong or unnecessary in Sri Lanka or elsewhere. The point is that those were ratified without much commitment, realism, proportionality, proper planning or follow up. This is one reason why the high ratification numbers internationally of the ICCPR (172), ICESCR (169), CEDAW (189), CRC (196) or other instruments might not make much sense in practice today.

Lopsided implementation?

There are several UN mechanisms to monitor the implementation of (1) the general commitments of human rights under the UN Charter and (2) the obligations under the ratified international conventions by member countries. The first type is called the Charter Based Bodies and the latter, Treaty Based Bodies. In whatever name they are called, the approaches seem to be going in a similar direction, the first type of bodies being more and more political and the latter type more and more legalistic.

The most controversial Charter based body today is the Human Rights Council. It oscillates between political and legalistic approaches. The US left the Council last year, after inflicting so much damage, but failing to sway the other members on the Israeli question. In my experience, the predecessor Human Rights Commission (1946-2006) was more flexible and balanced. There was no rigid bureaucracy like today, led by the Human Rights Commissioner and many so-called experts and officials. However, even during those days, the economic and social rights of the people in the world were terribly neglected.

To conclude, the main defects of human rights approaches both internationally and nationally could be identified as (1) the rigid and sterile legalism and (2) the pathetic neglect of economic and social rights of the people. Therefore, with over 200 international ‘instruments,’ the world has not progressed much since the inauguration of the Universal Declaration in 1948. This is regrettable. The most important conclusion, however, is not to throw the human rights ‘baby’ with the questionable approaches of ‘bath water.’ To save the ‘human rights baby,’ more and more social approaches are necessary with people’s participation.