Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Tuesday, 9 February 2021 00:44 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

It is perhaps timely to reflect on the nature and characteristics of who a Sinhala Buddhist is and perhaps should be – Pic be Shehan Gunasekara

“A man is not called wise because he talks and talks again; but is he peaceful, loving and fearless then he is in truth called wise. Even as a solid rock is unshaken by the wind, so are the wise unshaken by praise or blame” – Buddha

It appears that labelling oneself as a Sinhala Buddhist and the country as a Sinhala Buddhist nation is the national ethos while saying or implying that all others in the country are accommodated in the island because of the generosity of this national ethos.

It appears that labelling oneself as a Sinhala Buddhist and the country as a Sinhala Buddhist nation is the national ethos while saying or implying that all others in the country are accommodated in the island because of the generosity of this national ethos.

The purpose in writing this article is with the hope that it will generate some amount of contemplation and discussion as to who a Sinhalese is and who a Buddhist is, and perhaps who they should be. A question worth pondering is whether an outer garment matters more than the inner self of the person wearing that garment.

Historically, culturally and demographically, Sri Lanka has deep seated roots in it being predominantly of Sinhala Buddhist composition. There is no doubt that the Sinhala Buddhist orientation dominates the cultural ethos in the country.

Prior to the advent of the Sinhala race as believed and chronicled by the Mahavamsa itself, there were other human beings inhabiting the island when Prince Vijaya set foot in the country. If the Mahavamsa account is correct, they were not Sinhala people as Vijaya and his retinue is credited for the beginning of the Sinhala race.

The Sinhala race that Vijaya’s retinue began were mixed from the outset, as they produced their progeny with females who then inhabited the island and who were not Sinhala women. There is no record that Vijaya brought females from where he came.

Besides the then inhabitants not being Sinhala, neither were they, nor Vijaya and his retinue, Buddhist as Buddhism had not arrived in Sri Lanka then.

So, the conclusion one can derive, assuming the Mahavamsa account is correct, is that the Sinhala race began after Vijaya and his retinue, who were not Sinhala people when they arrived but Bengalis from Sinhapura, set foot in the island, settled in with the locals and produced the progeny who then were called Sinhalese. Interestingly, it is recorded in the Mahavamsa that Prince Vijaya in fact married a princess from India and they had no children, although it is also recorded there that he had two children with Kuveni, but they had apparently perished without trace.

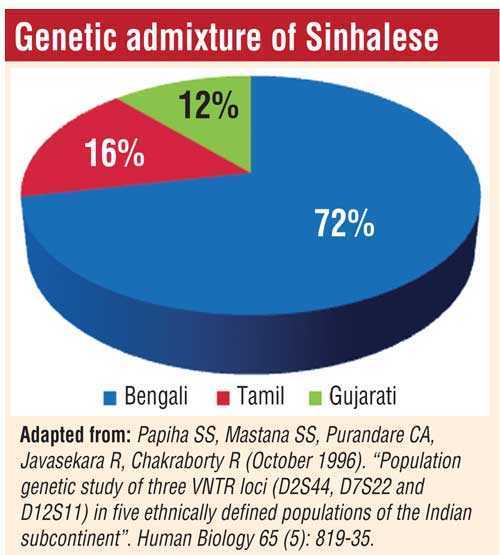

Given these accounts from the Great Chronicle, the Mahavamsa, mostly folklore, it is interesting to note the origins, at least genetically, of the Sinhalese people.

The Wikipedia states that quote, “All studies agree that there is a significant relationship between the Sinhalese and the Bengalis and South Indian Tamils and that there is a significant genetic relationship between Sri Lankan Tamils and Sinhalese, them being closer to each other than other South Asian populations. This is also supported by a genetic distance study, which showed low differences in genetic distance between the Sinhalese and the Bengali, Tamil, and Keralite volunteers. The up-country Sinhalese (mountainous region) and low-country Sinhalese have different genetic phenotypes according to observations, with the up-country Sinhalese looking slightly more Caucasoid, compared to the low-country Sinhalese, who’s castes are known to have origins in South India, although no formal study has been conducted on such matters. The vast genetic diversity of the Sinhalese has intrigued anthropologists on their genetic origins”, unquote

While there are many studies done on the genetic mix of the Sinhala race, the following perhaps is generally representative of historical mix and consistent with historical records of migrations into the island.

From these accounts, other research materials, and subsequent events, it does appear that the Sinhala race is a mixed race with genetic inclusions from many other races. This is not to say other races have genetic purity and a single genetic source. Most if not all races in the world, particularly where movement of people from one area to another and from one habitation to another occurred, there was mixing of races and today’s genetic research technology easily identifies genetic mixing in individuals.

The genetic mix of the Sinhala race makes them perfect candidates in a contemporary sense to show a greater understanding and accommodating of other races whose very genetic origins reside in them, and as Aristotle said, begin believing that the whole is greater than the sum of all parts.

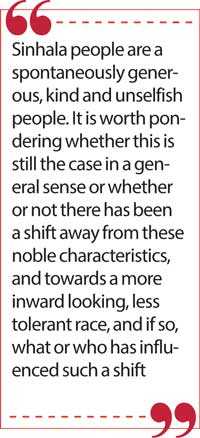

Sinhala people are a spontaneously generous, kind and unselfish people. It is worth pondering whether this is still the case in a general sense or whether or not there has been a shift away from these noble characteristics, and towards a more inward looking, less tolerant race, and if so, what or who has influenced such a shift.

Sinhalese and Buddhism

The Mahavamsa again records how the Sinhala race had protected Buddhism whenever there was a threat to Buddhism. Many Buddhists also go by the belief that Buddha himself had stated that Buddhism will thrive in Sri Lanka and it will be protected by the Sinhala people. It is unclear how Buddha could have said this as the Mahavamsa also reportedly records that Buddha passed away the day Vijaya arrived in Sri Lanka. The Sinhala race had not begun then for him to make that prediction although the proponents of this story also say that Buddha had the supreme mental ability to make such predictions. Such an ability would liken him to a God, and Buddha was emphatic at all times that he was a human being. If indeed Buddha had said that the inhabitants of the island would protect Buddhism, then, that would have made more sense as it would have included all other races in

Sri Lanka.

The question also arises as to how Buddhism could be protected and whether one is talking about the Dhamma or the Buddhist Institution.

Ven Bhikkhu Thittila in the February 1958 issue of the Magazine the Atlantic (The Meaning of Buddhism-Fundamental principles of the Theravada doctrine) offers this view about the teachings of Buddha: “All the teachings of the Buddha can be summed up in one word: Dhamma. It means truth, that which really is. It also means law, the law which exists in a man’s own heart and mind. It is the principle of righteousness. Therefore, the Buddha appeals to man to be noble, pure, and charitable not in order to please any Supreme Deity, but in order to be true to the highest in himself. Dhamma, this law of righteousness, exists not only in a man’s heart and mind, it exists in the universe also. All the universe is an embodiment and revelation of Dhamma. When the moon rises and sets, the rains come, the crops grow, the seasons change, it, is because of Dhamma, for Dhamma is the law of the universe which makes matter act in the ways revealed by our studies of natural science”.

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1958/02/the-meaning-of-buddhism/306832/

Ven Bhikkhu Thittila states further that “the teaching founded by the Buddha is known, in English, as Buddhism. It may be asked, who is the Buddha? A Buddha is one who has attained Bodhi; and by Bodhi is meant wisdom, an ideal state of intellectual and ethical perfection which can be achieved by man through purely human means. The term Buddha literally means enlightened one, a knower”.

If one is to call oneself a Buddhist, surely there cannot be an argument that Buddhism is or should be about the Dhamma and about what is in one’s mind. It is oxymoronic to associate the Dhamma with the institution as an institution cannot protect what is in a person’s mind. It is the Dhamma itself, and living by the tenants of the Dhamma that one can protect one’s mind, and therefore the Dhamma.

As Bhikkhu Thittila says further: “This doctrine finds its highest expression in metta, the Buddhist goal of universal and all-embracing love. Metta means much more than brotherly feeling or kind-heartedness, though these are part of it. It is active benevolence, a love which is expressed and fulfilled in active ministry for the uplifting of fellow beings. Metta goes hand in hand with helpfulness and a willingness to forego self-interest in order to promote the welfare and happiness of mankind. It is metta which in Buddhism is the basis for social progress. Metta is, finally, the broadest and intensest conceivable degree of sympathy, expressed in the throes of suffering and change. The true Buddhist does his best to exercise metta toward every living being and identifies himself with all, making no distinctions whatsoever with regard to caste, colour, class, or sex”.

It is perhaps timely to reflect on the nature and characteristics of who a Sinhala Buddhist is and perhaps should be. Do they live by the Dhamma and do they practice Metta? Can the Dhamma be protected by the Buddhist institution in Sri Lanka? Or is the institution a determinant of the political fortunes of individuals and political parties and the notion that Buddhism needs protection, a strategic survival ploy of the institution? Is this a symbiotic relationship that has mutual benefits?

History and the environment have created an identity called a Sinhala Buddhist as no one is that at birth. That identity could learn to live by the Dhamma or live by institutional dictates. It is no doubt a huge challenge for any individual as the environment pushes one towards the institution and away from the Dhamma. The institution fosters the opposite of Dhamma as the Dhamma is a threat to the institution. This challenge becomes even greater when national political leaders espouse the cause of Buddhist institutions, and foster and promote the display of the outer garments and not govern to strengthen the inner selves of the people.