Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Saturday, 1 August 2020 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The fight to save one of the planet's most important ecosystems

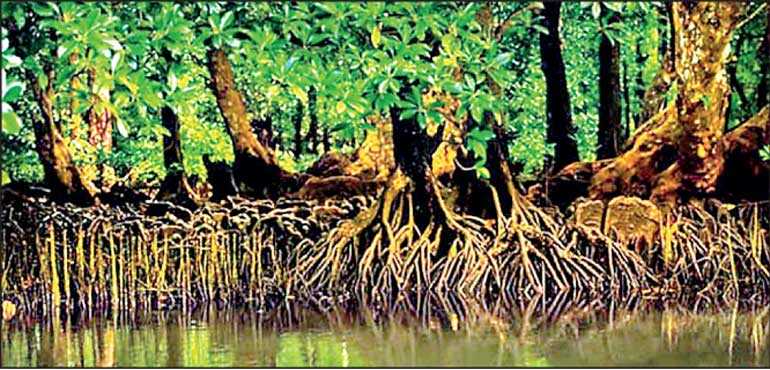

Deforested mangroves

By Madushka Balasuriya

By Madushka Balasuriya

Alright, let’s get it out of the way, mangroves are certifiably unsexy. Sorry, but it’s true. But like vegetables, daily morning stretching and regular health check-ups, they are objectively good for you - albeit not in as obvious a way.

Mangroves, you see, are the world’s silent heroes; muddy, smelly and buggy they may be, but a mangrove forest also mops up four times more carbon dioxide (Co2) per hectare than a rainforest. In terms of combating global warming and climate change, which primarily occurs as a result of excess Co2 being released into the atmosphere, mangroves might just be one of our best defence mechanisms.

Oh, and Sri Lanka just so happens to be home to a third of the known mangroves in the world.

But owing to their aforementioned unsexy nature, the importance of mangroves has tended to go under the radar somewhat.

Mangroves and Sri Lanka

This fact was highlighted as recently as this past February, when residents in Negombo staged a protest calling for the construction of a playground on an island which happened to have a high density of mangroves.

The story went viral after an official from the wildlife conservation department was filmed by the media standing up to outraged community members at town council meeting. The area residents’ grievances however were not completed unfounded, with them claiming that while a permit for building the playground was denied, the mangroves had nevertheless already been partially destroyed as part of the Negombo Lagoon Development project.

Environmental advocates have since charged that the lagoon project had gone ahead without an adequate environmental assessment, and in violation of the laws of coastal conservation; the country’s burgeoning coastal development plans have in fact seen mangrove cover reduce to less than 15,000 hectares across the island over the past five years.

These facts are all the more jarring when you consider that in 2015 Sri Lanka became the first nation in the world to comprehensively protect its mangrove ecosystem, launching the Sri Lanka Mangrove Conservation Project. Sadly, there is serious risk now of such initiatives becoming little more than lip service.

The pressure to clear pristine mangrove areas to expand aquaculture and salterns have continued in the intervening years, while at present the industry is even eyeing the de-gazetting of protected areas such as the mangrove forests in Vidaththalaithiv. To add to this, the impacts of waste accumulation, sand mining, river diversions, invasive plant species, land grabs and unsustainable fishing, escalate yearly.

“For a long time mangrove ecosystems have been viewed negatively, so much so that there had been no mercy shown to mangroves when it came to development,” explained Dr. Sevvandi Jayakody in a recent webinar organised by the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka.

“Since the 1980s we have been systematically removing mangrove ecosystems in the country, especially in the North-western coast and Eastern coast. Even after sacrificing large extents of mangroves, starting from Chilaw to Wannathawillu, and also the Eastern coast, there are still attempts to de-gazette what is already protected.”

Dr. Jayakody is one of the most competent authorities on mangroves in the country. Her research interests include coastal ecosystem management, policy and impacts of human disturbance on ecosystem processes and functions, and she currently serves as the chairperson of National Mangrove Expert Committee, is a member of both the Commonwealth Blue Carbon Initiative and National Environmental Council, and is a Director of Environmental Foundation Limited.

She recently presented an online lecture titled, “Do or do not, there is no try: Mangroves and their future”. In it she outlined in detail, mangroves, their importance, the problems they face, and what we can do to protect them.

The importance of mangroves

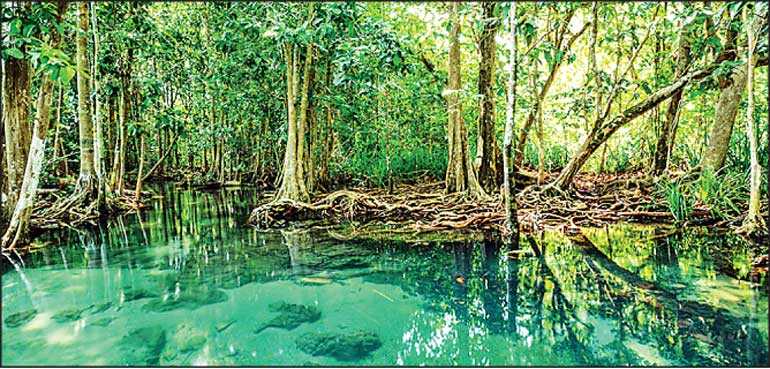

We’re all familiar with the term forests - but in this classification, about 87 hectares of land encompass mangroves. The ecosystem they create is known as the mangrove ecosystem. It consists in addition to mangrove plants (true mangroves), other plants commonly found in coastal areas (mangrove associates), micro and macro fauna adapted to live permanently or seasonally within this ecosystem, as well as the unique physio-chemical conditions created by tides, freshwater flows and silt.

Mangroves, which are found in over 120 tropical and subtropical nations, are known particularly for their resilience. Able to grow along coastlines, rivers and deltas, these salt-tolerant evergreens are a critical part of biodiversity and the environment.

“To a land animal or a plant, the sea is a very hostile environment; high salinity, wave actions and fluctuating water levels. They all present problems that are rarely experienced by terrestrial or freshwater habitat animals,” observed Dr. Jayakody during her presentation. “Nevertheless the two greatest assemblages of angiosperms of vascular plants have overcome these hazards and have successfully colonised the sea, and they’re mangroves and sea grasses.”

Mangroves also serve a litany of functions; they maintain the economy, climate, and marine habitats and seashores, aid in the filtering of water, prevention of erosion, and as such are enormous in terms of the value they provide.

They even provide more immediate protection, with studies showing that villages which have dense mangrove cover are likely to be less impacted by natural disasters such as tsunamis.

This adds to the already plentiful benefits mangroves offer to coastal communities in terms of providing livelihoods for fishermen. The stilted root systems serve as nurseries for many of the fish species that go on to populate coral reefs, and these fish populations end up feeding generations of coastal communities.

“Mangrove plants have created the right conditions for many animals, because this is the place with lots of food and lot of shelter. They’re even used by elephants, while mangroves are also the first stop for migratory birds.”

The world’s greatest carbon sink

But arguably the most important service they provide is in their function as probably the world’s greatest carbon sink combatting the greenhouse gas effect.

To be clear, the retention of Co2 in the atmosphere is a completely natural process that is required to warm the surface. Without this process our planet would be completely frozen and inhabitable. But where problems arise is through the entirely man-made Enhanced Greenhouse Effect, which has come about as a result of excess Co2 in the atmosphere - making the planet exponentially warmer in recent years.

About 80% of this global warming is down to fossil fuel emissions, which has mostly come from the burning of fossil fuels since the start of the Industrial Revolution in the mid-18th century, and also deforestation.

Among this deforestation is the destruction of mangrove ecosystems and this is severely handicapping the Earth’s ability to cope with excess Co2 emissions. Mangroves may only make up less than 2 percent of marine environments but they account for 10 to 15 percent of carbon burials.

“Carbon storage in mangrove ecosystems have been well studied, we know the amount of carbon that sinks in mangrove ecosystems yearly,” stated Dr. Jayakody.

“Mangrove ecosystems have the ability to sink carbon, way more than many of the terrestrial ecosystems that are known to us. Our future, our security, depends on conserving the mangroves.”

That’s right, by destroying mangrove ecosystems, not only are we limiting a key source of income for coastal communities, but we as a species are actively acting against our self-interest in our battle against climate change.

Problems and solutions

So what then are the problems we in Sri Lanka are currently facing in mangrove conservation? Well, as touched upon earlier in the article, unauthorised and poorly assessed development work is a major issue.

Shrimp farming is another critical issue facing the survival of mangroves, with shrimp farmers known to illegally cut down mangroves. There is also illegal logging that takes place.

One of the most pressing issues meanwhile is that large chunks of mangroves have been converted into salterns in the country, all around the coastal belt.

“Once abandoned they give rise to barren, very hostile landscapes, where no animal or plant can survive,” explained Dr. Jayakody.

But according to Dr. Jayakody, there are reasons to be optimistic.

“We’re used to talking about not having progressive thinking when it comes to conserving our natural resources. But when it comes to mangroves I think the story is different.

"Approximately 17000 hectares of land have been gazetted under Forest Ordinance. After gazetting the department of forests also did many things. For example, degraded mangrove lands in Mannar district were fenced to protect from cattle grazing and damage.”

Moreover, restoration of mangrove ecosystems have begun in earnest.

“So with expert advice and guidance, we started managing mangrove seedlings in the exact environment the restoration would take place, under the same trees in the same location, exposing them to the exact conditions where they would be growing later on.

“We were worried to start with, worried that they would not survive, but now they’re growing happily, and these plants will now be transported and used as the material for the restoration.”

According to Dr. Jayakody, these are the lessons that Sri Lanka is currently sharing with the world so that other countries can learn from our knowledge and expertise.

Though she warns that just because mangrove restoration is taking place, it doesn’t serve as an excuse to continue destroying mangroves ecosystems in other areas.

“Though we have 21 species [of mangrove], they are not found everywhere - two mangrove stands in the country are not the same. We cannot sacrifice one mangrove stand on the pretext that it’s found elsewhere, they’re very different; their composition, species diversity and distribution.

“So just because we have gazetted new mangrove areas, just because we’re restoring abandoned shrimp farms and salterns, that does not mean we have an excuse to destroy what is already present.”

But to ensure their continued protection Dr. Jayakody knows the best method is through increased awareness, while simultaneously putting pressure on the government to do the right thing.

“We are also at the moment getting involved with coastal communities, who are supporting the departments to grow mangroves in their back yards, so that two things can happen. It’s an income to the coastal communities, and through this initiative we’re also introducing them and exposing them to the importance of mangrove existence.

“In the end Sri Lanka needs to take a decision, either you want do it or you don’t want to. You cannot say, ‘we’re trying’.”