Friday Feb 27, 2026

Friday Feb 27, 2026

Saturday, 6 March 2021 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

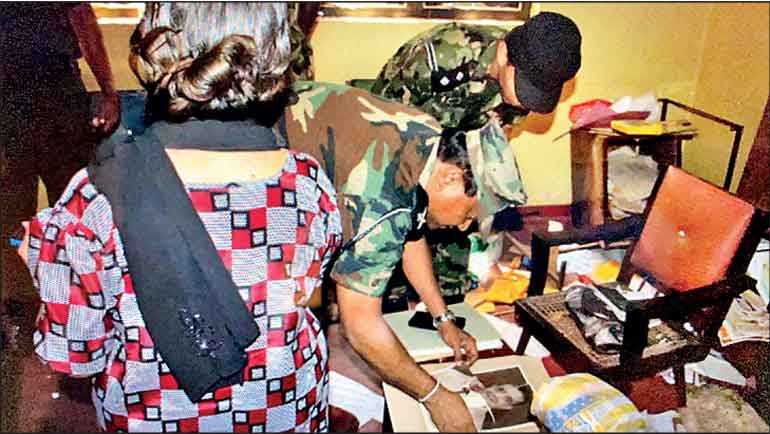

Major General Ubaya Medawela examining the destroyed photograph of the father of an aged Muslim English teacher affected by the Aluthgama unrest of 2014 and then handing over the restored photograph to her. He recalls: “She said that the only printed memory of him was torn to bits during the Aluthgama incidents. I collected the pieces, got the photograph restored and handed it over to her”

Former Chief of Staff (2016), Major General Ubaya Medawela has served as the Security Force Commander (Central and West), and as Military Advisor to the Office of Permanent Representative of Sri Lanka in the Sri Lankan mission to the United Nations in New York and is also a former Military Spokesman. He was appointed the Dean of the Asian Group of Military and Police Advisor during his official stay in the US from 2015 to 2016.

In this interview Major General Medawela speaks of some dimensions a Lankan peacebuilding model should adopt. He importantly draws on an environment-based model for national unity in Sri Lanka and highlights several essential aspects for establishing a stable and long-term peace plan for this nation. He emphasises on the importance of nature, culture, ethics, etiquette (as per national tradition) and how all of these should be within a structure of society for establishing a lasting and resilient bridge towards social harmony.

Having schooled at Nalanda College in Colombo, Major General Medawela has had an unbroken record in cadetting for over eight years and was the Sergeant of Junior and Senior Cadet Platoons in the ’70s and ’80s up to the age 12-16 and 16-20 categories respectively, considered as Junior and Senior, which he states

instilled in him a clear wish to join the military. The stringent discipline imparted through cadetting and the high expectations of that discipline had laid the foundation for him to play a leading role later when he held different responsibilities to groom, train and guide military personnel in line with military doctrine related to operations of war and related administration, logistics and rule of law. He is currently associated with a private company working as the head of compliance, health, safety, environment and security. Major General Madawela is a graduate of the Indian Defence Services Staff College and the University of Madras 1998, and holds an MSc in Defence and Strategic Studies with an Instructor Grading. He is also a graduate and an advance degree holder from the National Defence University of China and has followed specialist courses from USA, Europe and East Asia.

In this interview he draws on his independent views on a peacebuilding model for Sri Lanka and shares his experiences of the past where even at the height of war he had won the trust of the Tamil people who in several instances, in diverse ways defended his camp from being threatened. As military advisor of the Sri Lankan mission to the United Nations he had effectively secured the Sri Lankan military into the UN peacekeepers team in Mali and few other vacancies in the peacekeeping missions for Armed Forces and Police. He reiterates that peacebuilding for Sri Lanka should be because Sri Lankans genuinely want it and not because any foreign entity wishes it.

Following are excerpts:

By Surya Vishwa

Q: Recently you were Chief Guest at the Centre for Islamic Studies (CIS) newly-established Harmony Centre and you spoke on the importance of understanding nature and culture, inculcating ethics and etiquettes in communities as well as how the example set by each individual to guide others in society can contribute to creating a better future. Could you further elaborate the points you made?

In my speech I explained how the structure of society can help to understand the importance of coexistence and integration as well as the concept of bridging harmony through trust, mutual understanding, ingenuity, and integrity in the process of securing a common national patriotism and identity.

I also highlighted the basic fact that we are all part of Mother Nature. We come here to play a role on this earth and that role should be a positive one. Whatever the circumstances we have within us a humanity which is connected to the humanity of the planet. I contributed whilst in the Army to making men in green aware of the importance of conserving and protecting nature and launched a campaign themed ‘Prevent Disaster through Greenery’ when I was Security Forces Commander for the Western, Wayamba and Southern Provinces.

We cannot talk of peace or harmony without first reconciling with the fact that we are insignificant beings when considering the power of this planet – a tsunami can wash us away in a few hours and a landslide can sweep us away in a minute. It is how we treat nature that nature treats us. This is the same with humans – it is how we treat each other that will result in cause and effect of action. For me both culture and nature are important in connecting people. However while culture can evolve and change over time, Mother Nature remains constant and holds us all within her grip. Therefore we cannot connect with each other without understanding that for Mother Nature we are all equal. We may belong to different religions or ethnicities but the fact that we all go to the same soil when our last breath depart from this body has to be understood.

I have been a soldier from 1981 to 2016, the year I retired, and I know that when we go toward the battlefield we do so as a soldier doing his duty (as the Bagavadgita the Hindu epic points out) and never with the intention of killing out of enmity or anger. In battle when facing the opponent as circumstances decree, it is about self-preservation; if one is not fast enough defending oneself, the opponent will take the initiative first and your life can end in a second.

Q: You seem to function from a strong realm of practiced spirituality?

Well, I would not call myself religious as such. I belong to a Buddhist family. What matters to me is the genuine actualisation of Buddhist ethics and principles in day-to-day life. From a young age I have contemplated that one’s most valuable asset are ethics, discipline and honesty. These are aspects I encouraged in myself and in others in the military.

When I gave my talk last week at the Centre for Islamic Studies (CIS) I first asked the predominantly Muslim audience whether they think I am a ‘Buddhist’. What I was trying to say is that it’s the manner you conduct yourself that would decide who or what you are. ‘Character is demonstrated conduct’ and the self-actualisation of this statement is important for co-existence and harmonious living.

Q: According to you what is the most important element in having a national peacebuilding plan through which different communities could enjoy their human rights?

The most important thing is that it should be suited to the country, is ushered in with a genuine recognition from the people that it is needed for their own wellbeing and not owing to any compulsion by any outside entity. The focus should be on ‘national harmonisation’. I don’t believe that the correct term is ‘reconciliation.’ What is there to ‘reconcile’ when we coexist? In the entire history of this country we have co-existed – for centuries we have co-existed. Hence a peacebuilding model must be created within the framework of our heritage, nature and Sri Lankan culture surrounding the people. The model we should avoid is one that is based on an imported culture. If such a model is imposed it will not be fruitful as it would not be contextual.

Once there was a South American General who had given a talk in New York on a peacebuilding model as applicable to them and had commented that it could be replicated by Sri Lanka. Well, how can this be? That particular context is totally different. When it refers to guerrilla warfare, insurgency or terrorism, it is in the backdrop of a totally different situation. While it is certainly useful to look at different global contexts, to understand the seeds of conflict and examine peacebuilding in these different circumstances it is up to a nation and its people, to work towards a local peacebuilding model and to do so with absolute genuineness. We fought a war when terrorism was being carried out but it does not make ordinary Tamil citizens of this country terrorists. This is a salient fact. Within the past few years Sri Lanka has gone through few other difficult situations across the country.

We also had the Easter Sunday attacks. Extremism of any form, from any community shows us that we have a social problem we must urgently look into.

I have witnessed firsthand how hearts of human beings can be won over with genuine intention and action – there are countless narrations that I could give in the context of the 30-year battle against terrorism.

Our Tamil people, at the height of war, reacted positively when steps were taken to clearly distinguish between those carrying out guerrilla warfare and ordinary civilians caught in between the LTTE and the military. It is not easy for these people. Hence my main concern then, within the backdrop of a conflict zone and as a military officer, was to win the confidence and the trust of the people trapped within conflict zones. This is the most powerful way we could make major changes. I have witnessed these changes before my very eyes.

At the height of war, the military renovated several places of worship of different faiths, to provide an opportunity for those who lived in those areas. We took much effort to search and find the Hindu priests in charge of the local kovils which were till then largely abandoned.

The Tamil citizens of the north as well as east of Sri Lanka were quite stunned by these actions of the military and some of the local people who had stayed away from the military in these pockets of areas started speaking freely with us and worshipping at the Hindu temples we rebuilt. Also although the Muslims of north had been forced to leave that region by the LTTE by then, wherever we found small abandoned and derelict mosques we restored these as well and the Muslim community who returned later and also some of the Islamic military personnel started worshipping in them.

Overall, in my view, nature is the most dominant contributory factor for harmony not culture. To me ‘culture is anything other than nature’ which helps to boost the human moral component of life and this too helps but within the parameters of nature.

Q: What are the most powerful stories of trust-building at the height of war that you have come across?

It is mostly through the functioning of places of worships and through the education of children. To me protection of anyone is by the sheer goodwill energy of the people. This leads me to recall what the Poosari who officiated at a kovil that was re-constructed in the north told me, that the camp would be protected by the gods. This story came about after the Poosari was threatened by an LTTEer for taking assistance from the military to resurrect the kovil. The Poosari had responded saying, ‘God will take care of the good, not the evil.’ I wonder how many would have courage to say so. It is because he was genuine and we were trusted that he did so. To date he is hale and hearty. May the Triple Gem and all the gods he believes in bless him for a long and prosperous life.

There were several encounters we had that proved this Poosari’s prediction to be true. Our camp was never destroyed although there were attacks. This could be interpreted as superstition but the fact is that the collective energy of the people around was positive and we had countered the situation effectively with loving kindness as per the teachings of the Buddha. The result was that whatever the adverse context, the ordinary Tamil people of that area did not want us to be hurt. They knew that it would affect them as well to live in peace. ‘Winning war of minds’ is more important than ‘winning war of arms’. We have to keep this in mind if we are truly designing a peacebuilding plan that is comprehensive for Sri Lanka.

Q: You mentioned that education played a role in the military winning minds of the Tamil people in the north. Could you explain?

Yes. We had requests by the villagers to provide facilities for education for children in conflict ravaged areas. Villagers had confidence that if the kids are educated they would probably see the light at the end of the tunnel someday. So we honoured their request by finding the needed teachers and paying them through our officers’ contribution monthly to help in the education of the children. Time to time we provided refreshment for the children and life moved on amidst sounds of shells and bullets. Amidst all this the children and villagers enjoyed life with stage dramas we supported the schools to organise and with the military providing the sounds and music to make these entertainment events memorable for these people who saw only the darker side of life.

Q: Have you other examples of trying to bring Tamil and Sinhalese civilians together during the war?

Yes. It is not only Sinhala and Tamil but all communities which live in Sri Lanka. Whenever I could I have brought and still bring different aspects of pure Lankan culture to connect people together. In one initiative we used food as a means of human connection – by organising food festivals to introduce forgotten food taste of all provinces and compiled a recipe book too based on this endeavour. This led all communities and organisations from the smallest family to the Government to understand why different communities have different food habits and preparations. It is what nature has suggested them to live healthily as per the conditions existing in those areas.

Q: Could you explain what prominence the military generally gives to environmental protection?

As a rule all soldiers must protect and conserve nature. It’s for mere existence of all. Just think if we fail to protect the nature and share resources judiciously what will happen? It will lead to many problems including conflicts between communities based on the sharing of resources. That’s where the factor of sustainability comes; do not use resources more than what is required because it must be conserved for future generations.

Meanwhile, we must all understand that the military is not there to create conflicts or wars but to prevent them. Don’t forget that the most peace loving are soldiers. It is they who understand the pain and agony of war the most than any other. Those who don’t take part in war can talk about it, but the question is how much they understand the agony.

Q: You have played a major role in training within the military and now you work in the private sector. Could you comment on the importance of professional training in general?

In some walks of life or professions training can be a minor activity to which relatively little time and resources are allocated. The general assumption in relation to training is that it is often only with core businesses that manufactures goods or provides professional services. However, professional training is required in whatever the sector, or rank of the job.

In the military, the core focus of training is to meet any challenge in the spectrum of conflicts. The main preoccupation is the preparation for the possibility of real-life operational commitments.

Training for maintaining peace should be the military’s most important activity in peace time. Commanders should realise and work towards the importance of training to develop the quality of the personnel and the resources which they allocate for any commitment on the ground; from conflict resolution to peace building. It should most importantly include civil military cooperation activity. The ultimate objective of all training is to ensure success. Training provides the means to practice, develop and validate the results. There will be constraints as there is no perfect conditions for training. The practical application of the skills developed during any professional or vocational oriented training could be perfected best when working through the limitations. This is applicable for any profession or job across the public and the private sector. Training is compulsory for the maintaining of discipline, whatever one’s role in life is, however humble and to ensure social mobility.