Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Wednesday, 17 July 2019 00:09 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Chandani Kirinde

A retired senior Prisons Department official who has witnessed seven judicial executions says he is against the capital punishment as no judicial system in the world is infallible and there is a chance that a wrong person can be sent to the gallows.

“You can hang 100 guilty men but if you hang one innocent man, the system is a failure,” said H.G. Dharmadasa, a former Commissioner of Prisons, who officiated at seven judicial hangings including the controversial one of D.J. Siripala better known as Maru Sira in 1975.

Judges and juries, he says, can make mistakes and the manner in which crimes are sensationalised in the media which often blur the line between fact and fiction can influence judgments. “World over there have been several instances of the wrong person being hanged which is why I am opposed to the death sentence being carried out,” he said.

Another important factor to consider is that executions have not contributed to the reduction of crime. “Even when the death penalty was in operation in the country, crimes were committed. Out of all those sentenced to death, it is around 20% who were executed. Even if one commits a crime that carries the death penalty, criminals know the chances of them reaching the gallows is slim and hence will not be deterred even if a few are hanged.”

No judicial executions have been carried out in Sri Lanka since 1976 and the present moratorium of 43 years is the longest the country has had. Attempts have been made in the past to have capital punishment abolished but the law remains in place.

In May 1958, the Government of then Prime Minister S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike abolished the death penalty with the enactment of the Suspension of the Capital Punishment Act No. 20 of 1958, but it was short-lived. Less than a year-and-a-half later Bandaranaike was assassinated and his successor W. Dahanayaka’s Government reintroduced the death penalty with the Capital Punishment (Repeal) Act which was made effective retrospectively to punish those responsible for the Prime Minister’s murder. In July 1962, Talduwe Somarama, the man found guilty of shooting Bandaranaike, was hanged at Welikada.

Prior to 1968, all the execution was officiated by a person called the Fiscal who came from the Fiscal Department. The Department was subsequently abolished and the responsibility of officiating at executions was given to the Prisons Department.

When Dharmadasa joined in 1968, a part of the training was to witness an execution and write a small report. The day he first saw a man being hanged is still well-etched in his memory. “I remember coming to Welikada Prison early that day as I was keen to speak to the man who was to be executed. By then I had been in Prison service for just over a month or two. The Superintendent on duty, after some hesitation, let me meet the prisoner who had been moved to the cell next to the gallows as is the general practice to do so on the night before the execution.”

The condemned man, he recalls, was a fairly young man, a carpenter from Moratuwa. He was found guilty of murder, but he believed he had not committed any crime as the man he had killed was a menace to the entire village. “He said the man he killed was extorting money from innocent people and harassing all the villagers. One day he was returning home from work when the two came face to face, which led to an altercation and the condemned man had stabbed the other with the chisel which he used for his carpentry work, thus killing him.”

What Dharmadasa recalls about the man was his determination not to face death like a coward. “He told me he has a wife and young child and he had told his wife who visited him the previous day (a visit from next of kin is allowed the day before execution but under strict security) that if she finds a suitable man, to marry him and look after the child. He knew his fate was sealed but had no bitterness. After all these years, I remember him as a person who was out of the ordinary.”

Judicial executions are carried out under strict rules which are drawn from the Prisons Ordinance, Prison Regulations (Prison Rules) and the operational rules laid down in the departmental standing orders.

The process for the Prison Department begins with the letter sent from the President’s Office which sets the date and time for the execution. The time set is always 8 a.m.

After the letter is received by the prison authorities, maybe a week or even two days before the set date, the condemned prisoner is informed, and he is given special security from that time onwards with two prison officers assigned to him.

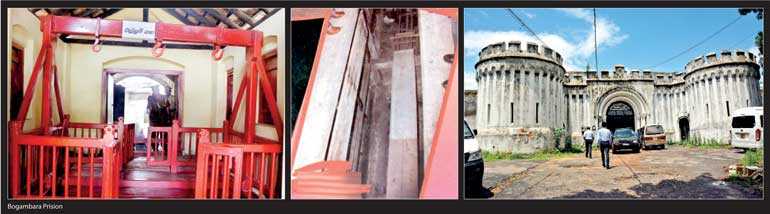

Executions were carried out only in Bogambara and Welikada Prison before 1976 and all the hangings that Dharmadasa officiated at were at Kandy.

“There were two executioners for the whole country at the time. They are informed of the pending execution and they must arrive at the Prison the previous day. They usually come by train as they are given a railway warrant to travel. Those days we did not have many vehicles. They bring with them a leather bag with all the paraphernalia needed for the hanging; the rope, a little pillowcase like cloth to place over the prisoner’s head and the suit that the prisoner has to wear when he is taken to the gallows.

“Once they arrive, the executioners are kept inside the prison gate because of the fear that if they go out there is a possibility someone can abduct them or they could meet with an accident and then there will be no one to carry out the hanging,” Dharmadasa said.

After their arrival, the executioners have something important to do. They have to weigh the prisoner on a normal scale, and they test the rope with a sandbag filled to the exact weight of the prisoner.

The next morning, the prisoner is prepared for the gallows. “There is a jumpsuit the prisoner is dressed in. There is also certain security equipment that is used. These are the leg straps that bind the legs close so that he can only take small steps while a body belt is also placed on the prisoner so his hands are restrained and cannot be raised above the elbows. A cap like a small pillowcase is placed over his head to cover the face once the prisoner is brought near the gallows.”

There are also very few officials who are present at the scene of a judicial execution. These include the Prison Superintendent who is officiating, the two jailers, or at least one of those who received the condemned prisoner when he was brought from court after he was sentenced. One of them must be present to identify him as the person they received. The Chief Jailor too can be present. The Prison Medical Officer and a member of the clergy from the religion that prisoner belongs to is also allowed to be present. If the man is a Buddhist, the monk will chant pirith as he is marched to the gallows.

Dharmadasa says it is normal to ask the prisoner if he would like something in particular for breakfast the morning of the execution, but these are also limited. “There is no truth to talk that they are given an adiyak (a shot of alcohol) if they make one such last wish. The truth is, many don’t eat anything. How can you expect a man who knows he is going to die an hour or two later to eat?”

For a death of a prisoner to end in a judicial killing, not only should the noose be placed in a right way by the hangman who is trained for this, but the drop, when the levers are pulled, must be calculated accurately according to the weight of the prisoner. “There is something called the ‘table of drop’. The drop from the gallows has to be calculated according to the weight of the prisoner. If the prisoner is too heavy and the drop is too long, then there have been instances recorded where the prisoner’s head has got severed.”

In Sri Lanka, Dharmadasa says, there is no legal document with the ‘table of drop’ but what was used in the past was based on the Singapore or Indian manual.

It is also mandatory for a post-mortem to be carried out after an execution so that the cause of death can be given even though this happens in the presence of the medical officer. The cause of death is normally given as ‘rapture of the spinal cord due to judicial hanging’. The body is handed over to the next of kin after the execution but burials are done under the supervision of the Prison officials.

However well-laid-down the procedures are for carrying out State sanctioned executions and however clinical the process looks from the outside, it is a traumatic experience for those who are legally required to carry it out, as the former Prisons Commissioner knows only too well.

“Even if I carry out official orders from the supreme leader of the country, I am still part of that process. I had to carry it out as it is my duty to do so but few know the trauma any civilised person undergoes when witnessing an execution.”