Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Wednesday, 28 February 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Dinusha Gunasinghe

By Dinusha Gunasinghe

In the past decade, the Government of Sri Lanka has been aggressively pursuing a campaign against tobacco with a view to reduce or eliminate smoking in the country.

In keeping with the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), which is a set of recommendations made by the World Health Organization (WHO), Sri Lanka has introduced regulations relating to the sale, taxation, pricing and packaging of tobacco products.

The Minister of Health has also stated on various occasions that the Government was preparing to enforce bans on the sale of cigarettes in stick form, the sale of cigarettes within a radius of 500-meters from a school, or religious place of worship, and introduce plain packaging.

While there has been a lot of work undertaken to curb smoking in the country, the Government has focused its attention mainly on curtailing the legal cigarette industry whilst ignoring the other tobacco products that are thriving as a result. The Government driven price increases in legal cigarettes last year also resulted in the unintentional surge of illegal fags being smuggled into the country.

Despite the Government’s rigorous taxation and regulations on legal cigarettes, overall smoking rates in the country have gone up, driven by the record high levels of smuggled cigarettes that have been flowing in, as well as the rise of beedi – an under-regulated, hand-rolled tobacco product, which is a much cheaper (and potentially more harmful) alternative to legal cigarettes.

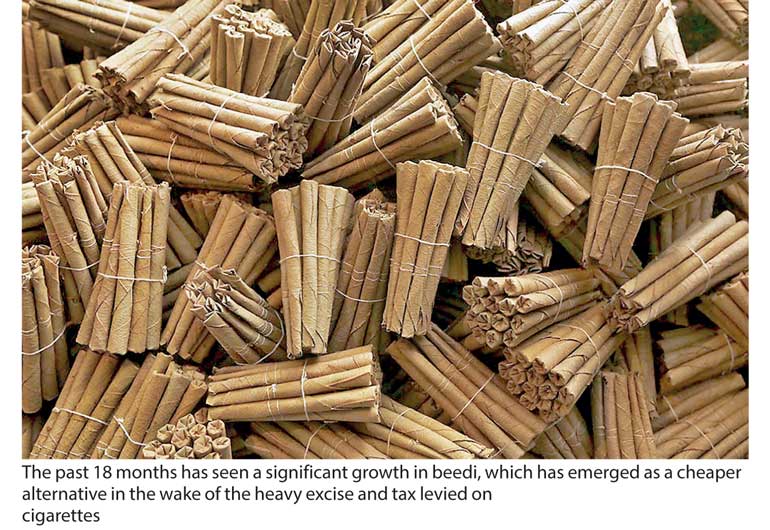

The past 18 months has seen a significant growth in beedi, which has emerged as a cheaper alternative in the wake of the heavy excise and tax levied on cigarettes in 2016. The 43% tax hike imposed during the last quarter of 2016 only impacted the legal cigarette industry. This effectively meant that Sri Lankan cigarettes are now the second most expensive in the entire world and the most expensive in the Asia Pacific region.

Given that purchasing legal cigarettes is becoming more and more expensive, consumers who find it increasingly difficult to reach for a cigarette are now switching to smoking beedis, which has remained a low price alternative thanks to the Government’s decision not to implement a recommendation by the cabinet to increase cess on imported tendu leaf from Rs. 2,000 to Rs. 3,000 per kilogram.

The price of the cheapest legal cigarette is now Rs. 20, while the price of a stick of beedi is anywhere from Rs. 3-5. Unsurprisingly, while the monopoly cigarette manufacturer has reported declining sales due to this high taxation, beedi sales have seen a remarkable increase.

While anti-tobacco lobbyists are quick to refute the increase in beedi volumes over the past 18 months citing Customs records of tendu leaf imports, on the ground statistics show that beedi manufacturers have found creative methods to obtain their tendu requirement. In fact, there have been several reports in the media recently of tendu leaf smuggling operations from India and the detection of tendu bundles floating in the sea off Hikkaduwa is further proof that smuggled tendu reaches Sri Lanka by such means. Furthermore, manufacturers are also known to hand carry stocks of tendu leaf into the country by avoiding detection at various ports of entry.

In light of this trend, beedi producers have seized the opportunity to capture the tobacco market, and as a result the production of beedi has doubled in many districts. For instance, in areas like Kegalle, Anuradhapura, Monaragala and Badulla, more than half of the villagers are engaged in producing beedi. Here, each family’s production averages close to 1,000 sticks a day, and they are able to make a profit of Rs. 650 for every 1,000 sticks made.

Contrary to popular belief, beedi is no longer just a cottage level industry. While it is true that Beedis are rolled by women and is carried out at the household level, the industry itself is a highly-organised operation, and run on a huge scale by large players unseen to the public. In many cases they also enjoy political support and patronage, which would explain why they remain untouched by the regulations and taxes applicable to tobacco products.

Beedi enjoys preferential treatment from the Government with no Excise taxes being levied on the final products. The only taxes levied on beedi are on the tendu wrapper, which is imported from India. However, this amounts to only 3% of the total tax revenue received from the tobacco market (Rs. 2.8 billion), and even this does not accurately reflect the real beedi market because many producers forgo purchasing the tendu wrappers, although they are required to do so by law.

Thus, the tax burden in this case is solely on cigarettes, which contributes an astonishing 97% of tax revenue to the Government. As a tobacco product (especially one that is unregulated in terms of product standardisation), the Government should take measures to ensure that price and taxation policies apply to beedi as well.

Beedi production and consumption is largely unaccounted for by Government authorities and advocates for the anti-tobacco movement, despite the large (and still growing) portion of the tobacco market captured by beedi. This accounts for a large loss in tax revenue to the government. Leaving beedi under-regulated and under taxed also means that the government is not meeting its own public health objectives by making a tobacco product easily accessible to smokers.

The absence of a legal framework for the beedi industry and its producers also means that beedi bundles being sold are not required to carry any form of health warning labels which cigarette packs must carry by law.

By successfully evading the notice of policy makers and law enforcement authorities, coupled together with the low pricing, beedi entices consumers – in particular, a growing number of young consumers. As a result of this, beedi has grown in popularity amongst the low income earning rural as well as urban populations.

A consumer can purchase up to five beedi sticks as opposed to one stick of the cheapest legal cigarette available in Sri Lanka, which easily makes it one of the most inexpensive forms of smokes available in the country.

Since beedi is mostly consumed by the daily wage labourer who is unaware of its health effects, perhaps a health warning is more suitable in this case. As a result of the lack of information on beedi and the myth that it is not a tobacco product, consumers freely purchase the product unaware of the harmful consequences of its consumption.

The Government’s efforts to eradicate cigarettes are commendable, but it surprising that the beedi industry thrives in the shadows and remains unchecked through regulation or taxation. It is time that the authorities identify and close the loopholes that exist in the system that allow beedi to thrive despite all the efforts taken to wipe out smoking from Sri Lanka.