Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Wednesday, 1 November 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Shehana Dain

By Shehana Dain

Despite the complete turnaround in economic policy 40 years ago, benefits and affluence would be much greater if economic freedom of Sri Lankans is increased, researchers opined at a live-streamed panel discussion.

The panel assessed 40 years of Sri Lanka’s open economy and kicked off a three-day forum on economic freedom organised by Advocata, a Colombo-based think tank.

Advocata partnered with Canada’s Fraser Institute, the publishers of the Economic Freedom of the World Report, and Atlas network, an international network of free-market think tanks.

The roundtable discussions brought together people from Government, industry, academia and think tanks to identify areas needing reform in Sri Lanka’s economy.

In the recently released 2017 Economic Freedom of the World Report, produced by Canada’s Fraser Institute, Sri Lanka ranks 94th out of 159 jurisdictions taking into consideration various dynamics. Sri Lanka’s growth may sound impressive, but considering Taiwan, which has long had a high level of economic freedom and ranks 32nd in the world, its economy on a per person basis is eight times larger than it was in 1977; almost double the growth of Sri Lanka.

In terms of economic freedom, businesses can freely enter the market and consumers have choices. With a world of choice, every exchange must benefit both parties or the party that comes up short would reject the exchange and go elsewhere. This forces producers to constantly improve price, quality and innovation, driving productivity and economic growth and creating jobs.

However the ground reality for Sri Lanka is far from basic economic principles as the country tried to embed free economic principles into deep-rooted socialist values.

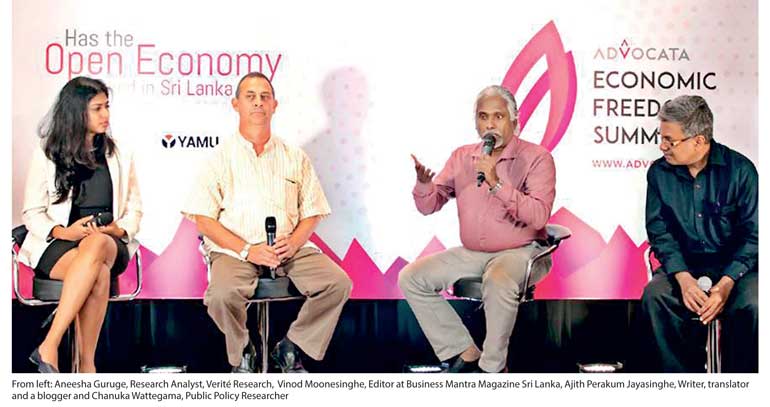

Thus the debate which featured Public Policy Researcher ChanukaWattegama, Business Mantra Magazine Sri Lanka Editor Vinod Moonesinghe and writer, translator and blogger Ajith Perakum Jayasinghe delivered diverse notions and was moderated by Verité Research Research Analyst Aneesha Guruge.

The debate went right to the point as Guruge raised the first question inquiring if the open economy has worked in Sri Lanka. Steering a middle course, Wattegama opined that the answer to that was yes and no.

“I belong to the so-called Generation X in Sri Lanka who were born in the 1960s. Fortunately or unfortunately we spent our childhood under a much closed economy and we have first-hand experience. If I compare the economy prior and following 1977 technically the open economy has worked for us. It has brought changes which we never thought possible. However if I compare countries like India and South Korea after they liberalised their economies and where they are now, I’m deeply unsatisfied about Sri Lanka’s performance,” he said.

Wattegama was of the view that for a country like Sri Lanka, which is a very small and tight market, protectionism is not the way forward.

Jayasinghe stressed that Sri Lanka never had a fully open economy. “In my perception this openness is relative to what was before and what’s expected to come. For example 1977 is considered a benchmark for this and we claim to have really opened the economy, if we have done so in 2017, 40 years after 1977, today on the street we won’t ask the basic question if we really need private education in the country.”

He went to say that the current scenario didn’t depict a true openeconomy and that the Government in 1977 and subsequent policymakers had merely relaxed barriers.

“When we were stuck and couldn’t move beyond a point we relaxed certain things. That’s what happened in 1977 and what’s interesting is that in 1978 we brought a new constitution and we changed the name of our country as well. We renamed it Sri Lanka Democratic Socialist Republic. If we are an open economy, why did we rename it as a socialist republic?” he said.

The public sector maintains a huge middle class which is also the most powerful in the country. Jayasinghe noted that policymakers find themselves in quite a fix as the powerful civil majority in Sri Lanka don’t actually want to open the relax trade barriers fully due to the fear of status depletion.

“In terms of fiscal policies the existence of State banks are very important for the middle class. Due to this, local polices are maintained in a way these banks can be protected. We are not liberalising our railways because we want to protect the Sri Lanka Railway Department to basically protect the jobs of this State institution. This openness is therefore always controlled to a certain extent,” he added.

According to Jayasinghe, currently Sri Lanka is at middle ground. “Now we want more economic sanctions to be lifted and relaxed because we can’t move ahead. When we look at it in a political lens what we are doing is maintaining a very big powerful middle class. Today we have no alternative and we have to go for economic liberalisation.”

Taking a different view point,Moonasinghe stressed that the economic policies before 1977 encouraged innovation as opposed to opening its doors for free trade.

“Today we are unable to pay for the stuff that we import because we’re not producing enough. That alone is enough to show that the open economy has been a failure over the last 40 years. We never had a socialist economy, we always had a colonial economy and we have not gone beyond it still,” he said.

He went on to say that the Sri Lanka does not have a capitalist class in this economy.“What we do have is a mercantilist economy. A mercantile class exists by importing stuff from abroad and selling to the people at massive profits.”

Citing an example for the lack of an industrial eco system in Sri Lanka, he noted: “At one time Nauru was one of the richest countries of the world; the phosphates finished and now they’re one of the poorest. This was due to the lack of an industrial infrastructure. In Sri Lanka we do not have an industrial eco system as well. We have a system of trade.”

Moonasinghe reiterated that until 1977 there was a positive attempt made to break out of this situation. “We did it in the same way that South Korea, Japan and Taiwan did it. They imposed very strong import regulations.The restrictions on imports did not come about due to ideological reasons. Socialists do not believe in regulating imports, they believe in getting as much as possible for ordinary people. Up to 1956 the country was spending on consumption and we were not spending on production and this was the fundamental reason for introducing import control.”

Citing yet another example as to how countries have thrived due to industrial eco systems, he highlighted: “In 1981 Taiwan had the same GNP as Sri Lanka. The difference was that Sri Lanka’s manufacturing was only 15% of the GDP whereas in Taiwan it was 31%. That is fundamental difference in this country. We do not innovate. Until 1977 there was a lot of innovation because we tried to improve our own manufacturing capability.”

According to reports, in 1977 manufacturing amounted for 23% of the economy, saw a sharp decrease to 14% by 1983, and in 2017 Sri Lanka is still at 19%.